A Coming of Age

A fond look back at the car that forever changed the way India drove

All of us in Chanakya Puri knew the Pitts S-2A biplane, could pick the tiny speck out of the sky, ducked when the pilot flew a shade too close to the shallow rooftops or did a risky set of roll-and-dives over Palam Airfield. On that June day in Delhi, the insistent mosquito buzz of the biplane could be heard by the last of the morning walkers as it brushed the tops of the gulmohar and amaltas trees. It took a few seconds for us to register the sudden absence of sound, a pause that opened up and then never ended, that marked the end of the Sanjay Gandhi era.

None of us in Chanakya Puri actually saw the plane go down. We did see the stately lady who arrived in an official Ambassador — these were the days before VIPs travelled only in entourages — and looked out with grief-reddened eyes over the fields where her maverick, risk-taking son had crashed, searching for something, a twist of steel, wreckage, not visible in the hard stubbled grass.

This was 1980, and later that June, my father took us out to India Gate for ice-cream. We travelled as we always did, a bunch of the neighbour’s kids packed in with me and my siblings like squirming minnows in the capacious belly of the family Ambassador. There was no traffic, as it is understood now; just a smattering of Premier Padminis trundling behind the ample, rounded elephant sway of the Ambys, the monotony of these two cars broken by the occasional appearance of a Baby Austin or Studebaker.

In 1980, the year Sanjay Gandhi crashed, the Maruti project was nine years old. It had been handed to Sanjay around the time of the Bangladesh war, and there had been muted criticism that he’d received the exclusive licence to manufacture what was being touted as the People’s Car. Within a year of his death, Maruti Udyog was formally established in February 1981. By 1983, the first Maruti had rolled off the line. Like thousands of Indians, our family rushed to join the queue for a new Maruti.

These days, if you’re coming back from a Rajasthan vacation, a business trip to Jaipur, you’ll see them on the last lap of the long highway snaking into Delhi: The massive, hulking shapes of the car-carriers, like frigates steaming into harbour. Every other vehicle on the road will stop to let them through, and one of these monsters, carrying 20-odd shiny new cars at a go, can tie up a toll gate for hours.

There are at least 26 car manufacturers in today’s India, offering everything from Range Rovers to Hyundais to dinky little Revas, and more knocking at the gates, a dazzling smorgasbord of models laid out in front of India’s consumers, with the promise of more to come. We take it for granted. We grumble that we don’t have the full banquet, just the appetisers and a small selection from the vast main courses available in other parts of the world. When we do make our choices, Hyundai versus Honda, Toyota versus Mercedes, we expect delivery the next day, a few sweeteners from the showroom guy.

Back in 1983, the main feature of the average Indian’s life was the queue and the long wait. You queued for black Bakelite phones, and then you queued for the privilege of meeting the linesman who would finally activate it, and then, at home, you queued for prebooked Demand or Lightning calls to another city and counted yourself lucky if the call came through in 24 hours. You queued for gas connections and for a token at the bank that would allow you to step up to the counter in 10, or 30 minutes, or an hour if you were unlucky, to collect your cash.

The big surprise about queuing for a Maruti 800 was that you got one in just months rather than years — unnervingly rapid progress for that generation of Indians. I remember a friend’s parents paralysed by choice, slowly scanning the selection of colours — black, white, red, dark blue, light blue and I seem to remember a sickly green — in disbelief that anyone would actually ask them what colour they wanted their car to be. And Maruti was, under R.C. Bhargava’s management, stunningly fast for the era — by 1985, they had rolled out not just the 800 but the Omni and the Maruti Gypsy. It is hard to explain just how dazzling it was to have three models to choose from, how rich it made the average office-goer with his State Bank of India account feel.

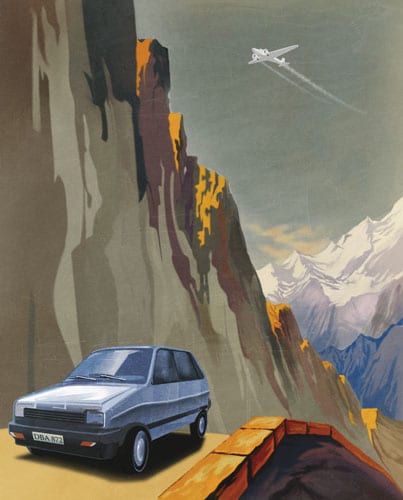

I wasn’t old enough for a driving licence when DBA 872 came home, but I was old enough to fall in love. Except for the very few Indians in that generation who had lived abroad, driven something other than a “Fiat” or an “Amby”, most of us had grown up with a sense of a car as an unruly, clattering beast with an awkward temperament and more sturdiness than grace. In our eyes, the tiny powder-blue 800 was a miracle of speed and fluid lines, a gazelle weaving its way through a herd of cows and buffalos.

It took time to see how deeply and inexorably the Maruti 800 changed India. The Fiat and the Amby were lumbering cars, the steering wheels requiring power and force. My mother drove an ancient World War II Ambassador, my grandmother in Calcutta zipped around in her ornery Premier Padmini, and over the years, both of them had developed the kind of upper arm muscles that today’s gymming crowd would kill for. Even the frailest of women could handle the 800’s light, inviting steering, though, and the low seats gave you a different view of the world, of the road, a sense of immediacy and excitement where the Amby gave you distance and enclosure.

And there was the chauffeur factor. In a country where you measured your importance by the distance between master and servant, the Maruti 800 forced an unruly democracy. It was built for families, for teenagers gingerly exploring this new concept called dating, for couples with the requisite two kids; the most comfortable seats were the driver and passenger seats in front, and those in the back had to put up with a certain amount of jouncing, especially when the speedometer crept past 80 kmph. Besides, a chauffeur-driven Maruti looked silly. It just did, and that forced a social change — it became slowly acceptable, even fashionable, for even senior bureaucrats and corporate chieftains to drive themselves. (This would reverse itself in a generation, when other car companies opened shop in India offering bigger, more luxurious saloons.)

DBA 872 and I got on well right from the start. I drove her illegally as a 16-year-old, taking her for short spins around the neighbourhood, tasting freedom like so many of the drivers in my generation who grew up in the Maruti years. We didn’t know, and didn’t care, that the plastic-and-rexine innards of the Maruti 800 were tacky, that it wasn’t by any standards one of the great cars.

It slid into a very Indian gap, between the sarkari years of the Ambassador’s reign and the flashy, consumer-driven decades of the BMW and the Merc. It was the first car that promised my generation a kind of freedom that had been unimaginable; the freedom to do long hill drives, to spend a romantic evening out just driving around your city, to party-hop because you could, to cram, improbably, 15 friends into the car on the way back from college.

I drove DBA for 17 years; she accompanied me into my marriage and saw us safely through the first years of houses-with-water-problems and jobs-with-desperately-anorexic-cheques. By her 10th year, the 800 had become ubiquitous on Indian roads, referred to derisively as the macchar (mosquito) by bus and truck drivers who hated the little car’s ability to zip around them on the highways. By the time DBA 872 was 18, she’d been left far behind on the fashion charts, overtaken by a smart new generation of cars from America, Korea and Japan.

Most of my generation of drivers have moved on, most of us upgrade our cars every two years in the same way that we efficiently remodel our careers, reshape our marriages, rework our retirement plans. We have our dream cars, and then a new wave of models comes in, and we have another set of dream cars, and we have the safe, acceptable backups that will do even if the Lamborghini stays out of reach. Those who’re buying their first Nano are already looking ahead, hoping for the Honda years, the Toyota years. Very few of the bright young Indians I know would consider driving the same car for 17 years, and that’s a sign of progress.

But when I think of DBA 872, what comes to me is a memory that has little to do with nostalgia. It’s a memory of the first time I took that old blue car out for a spin on roads that were sparsely populated, almost bare by today’s standards, the fierce thrill of pride that we felt as a generation in our new Marutis, the jolt of touching the accelerator gently and feeling the car speed up to a dashing 70 kmph.

Twenty five years down the line, I know that there was a measure of naiveté in that pride — we boasted of our 800s in such innocence, because we had no idea that there could be better, faster, sleeker cars in the world.

We broke coconuts over their bonnets when, the long, patient wait over, they came home. We revelled in the fact that any mechanic, anywhere in India, could repair a Maruti with a piece of string and a little faith. We boasted when we floored pedal to metal and managed to cross the 110 kmph barrier — the car’s panels juddered in warning at 120.

We treated the Maruti 800 like it was the best car ever made in the world, and for a while, it felt like it was.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)