Why a Resurgent American Economy Matters for India Inc

Move over economic depression. For Indians, America might just be back with a bang

Fall in Canada is splendid. Around September to early October, for a couple of weeks every year, the changing leaf colours attract thousands of visitors. Two years ago, Dow India chairman Vipul Shah and his wife decided to take a trip to see the sight. There is this one train that goes to this place in Ontario, where the colours are at their best. It leaves early in the morning and returns from the small town of Sault Ste Marie.

The Shah couple was staying at a hotel across from the station to catch the early train. “We went down for dinner in the restaurant at the hotel. Both of us follow a totally vegetarian diet. So we asked the waiter what they could offer us,” says Shah. “Give me a minute,” said the waiter.

In a couple of minutes, the French-Canadian chef came out and listed the options: Vegetable curry, naan and basmati rice, with papad and mango pickle! The Shahs were stunned. Just as they were recovering, he dealt the coup de grace. “Or would you prefer a Jain meal?” he asked.

The chef revealed the secret a few minutes later. Sault Ste Marie, in Algoma district, had only one large employer: Algoma Steel. When the company went bankrupt, the town was in real crisis. That was when Essar Steel rode in from the East.

They took over the mill and invested to revive the mill as well as the town. While this was going on, Essar executives from India stayed in this hotel with their spouses. After a few days of eating nothing but vegetarian pasta, they approached the chef. “They asked me if their wives could use the kitchen to cook a vegetarian meal. I said, sure, but you will have to teach me as well. Now, we have Indian dishes on special request,” says the chef.

The steel mill at Ste Marie is now the second largest steel producer in Canada. It also serves arguably the best Jain meals upwards of the snow line.

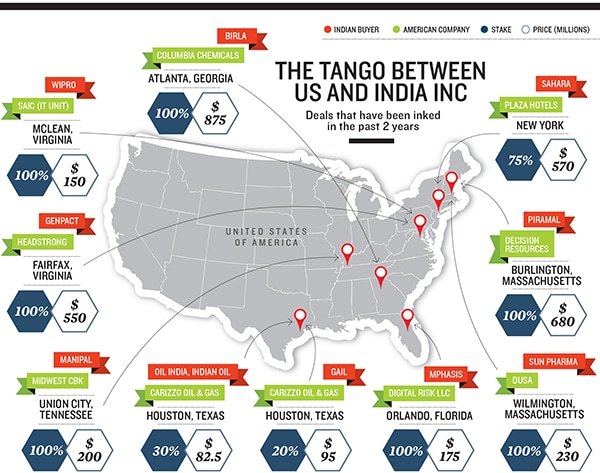

The Essar deal was sealed in 2007, but in the last one year, more and more Indian firms have been heading to North America to use it as a base for business. Consider this: Indian direct investment in the US, according to the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, has gone up from $2.55 billion in 2009 to $4.88 billion in 2011. From 2005 to 2007, it was flat at $1.6 billion. Over the last one year, the S&P 500 index has delivered more returns than all other major indices, including Nifty50, Hang Seng and FTSE100.

It is no secret that the Indian corporate sector has had four frustrating years since 2009. Investments running into billions of dollars are stuck for lack of government clearances and fuel shortages.

Entrepreneurs across the board are reeling under high debt and most have lost their appetite for any more investments. The income tax department has been busy sending tax demand notices to multinational firms of all hues to pay up backdated taxes. Responding to the changed scenario, many Indian firms are figuring out how to use the US more strategically.

Essar, Reliance Industries Limited and Aditya Birla Group lead India Inc in terms of investments in Canada and the US. But they are not the only ones. Smaller companies like Welspun Textiles, Jain Irrigation, Virgo Engineers, Motherson Sumi, Varroc, Uniparts and dozens of others are all leveraging Uncle Sam’s intellectual and financial capital. The new driver is plummeting energy costs. Not surprising that the Indian consulate in the US is urging Indian companies to invest in the American gas chain. India pays close to $16 to import one unit of natural gas while gas prices in the United States are close to $4.

The 9/11 attacks symbolised a global hegemon that was well past its heydays. When the US initiated the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it came as a further confirmation of the fact. By 2009, with its financial institutions under siege because of the housing price collapse and the beginning of a credit squeeze, it looked like the world’s largest economy was ready to give way to giants from Asia and other emerging markets.

Now it looks like the naysayers were wrong; and how!

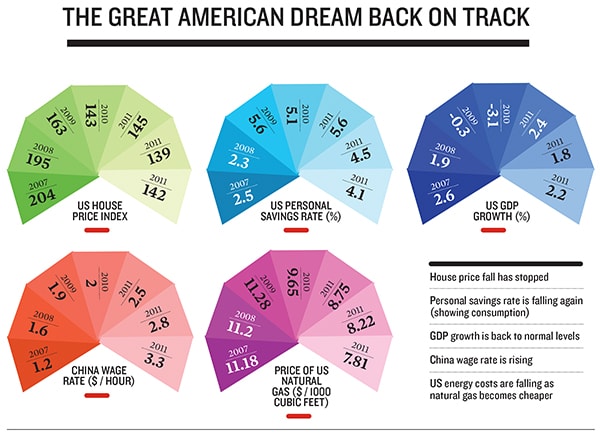

A recent McKinsey Global Institute study shows that the United States is the only major developed economy that is following Sweden and Finland that were able to negotiate similar debt-induced recessions in the 1990s. Debt to GDP in the US has fallen 16 percent in the last five years. In contrast, the ratio is rising sharply in Germany, United Kingdom, France, Italy and Spain. As with Sweden during the ’90s, the fall in US debt is entirely because of cuts made by the private sector, particularly the financial industry and households.

Over the last two years, real estate prices have stabilised and the savings rate has improved, energy costs are down and the cost of finance remains one of the lowest in the world. All this while Europe has slipped and emerging markets such as India and Brazil have stalled. China was one exception in the past. Its advantage of cheap manpower, a fixed currency, land and infrastructure were everything the US did not have. The advantages have weakened somewhat. Jagdish Sheth, Charles H Kellstadt Chair of Marketing in the Goizueta Business School at Emory University says, “Most multinationals are seeing the US turnaround as a great way to de-risk their dependence on their own countries and regions.”

For Indian companies, there are at least three interesting themes. The first is a play on the US’ attempt to become net energy exporter. The second theme is the return of manufacturing. As the energy costs have fallen, a range of industries—metal forming, aluminum, petrochemicals—are looking to return to the US. “The fact that the US is both the world’s biggest market and the world’s largest sourcing destination does help,” says Sheth. The third theme is Indian companies using the US and Canada in tandem to leverage natural resources and commodities.

In Breakout Nations, economist Ruchir Sharma says the most dramatic signs of a US revival are in manufacturing. Even as it was losing out to emerging manufacturing powers in the last decade, it was also reacting quicker than other rich nations by restraining wage growth and boosting productivity of remaining workers with new technology. This has allowed a steady fall in the dollar and made exports more competitive.

China’s rise has come largely at Europe’s expense. Since 2004, China has gained market share in the export of goods and of manufactured goods, while Europe’s share is falling and the US has held steady. After losing 6 million manufacturing jobs in the last decade, the US gained half a million in the last 18 months, while Europe, Canada and Japan lost jobs or saw no change.

Sharma also points out that energy is emerging as an American competitive advantage. After falling for 25 years, the share of the US energy supply that comes from domestic sources has been rising since 2005, from 69 percent to around 80 percent, due to increasing production of oil and particularly natural gas. The textile business was one of the first to leave the developed world, but recently Santana Textiles moved from Mexico to the US due to lower energy costs.

In the 1960s, the US Gulf of Mexico was the hub of the global petrochemical industry. This changed over the years, as it became cheaper to produce in Asia and the Middle East. The shale revolution has led to a revival of interest in the region. Dow Chemicals has re-started its Texas cracker plant in December last year—it had been moth-balled in 2008-09, when the slowdown began. Dow is also putting up another huge facility at Freeport, Texas, that is coming online in 2016-17. “The idea is to take advantage of the low prices, to serve the Latin American market from the US. We are also doing this in Saudi Arabia—using the oil to cater to the European markets,” says Vipul Shah, CEO and chairman, Dow India.

Consider how two Indian firms, one a behemoth RIL and the other a fledgling Virgo Engineers, are showing the way on using the energy exports theme to their profit. For RIL, it would mean a good share of profits coming from America, while for Virgo it would be both a big boost to sales as well as profits.

RIL saw a potential in the US well before others. Its second Jamnagar refinery was built to export high-quality refined petroleum products, particularly to states like California that used them and were willing to pay a premium for them. But from being an exporter to the US, in the summer of 2010, RIL chairman Mukesh Ambani took a huge plunge—diving deep into a business that is at the heart of an energy revolution in the United States. The move positioned him to be a gas producer in the US and eventually an exporter to India. By the time he entered, the shale boom had begun running out of steam in the US. Gas prices were falling and operators were shutting down gas wells, producing only from those that yielded associated liquids that were more valuable. Yet Ambani, a chemical engineer, was able to see through this and spot the opportunity for RIL and energy-hungry India. RIL moved fast, and one after the other, bought into three of the largest shale assets owned by Chevron, Carizzo and Pioneer Natural Resources. In the three years since, RIL investment in the JVs has crossed Rs 22,000 crore ($4 billion). “If you are talking about the US play, I would say Mukesh Ambani has been really smart about it. He saw it well before many others did,” says Ron Somers, president, US-India Business Council (USIBC).

Equally hungry for energy, Chinese and Japanese companies have also bought into US shale producing companies. The investment is not hugely profitable, as gas prices in the US remain depressed. RIL has what no other non-US company has been able to achieve. It has drilling permits, and is cleared by the US department of environmental protection to be the operator of the fields. It could soon be the operator at fields in Pennsylvania, gathering experience that can be invaluable back home.

Shale exploration and production is a completely different game from production of conventional natural gas. Fracking is used to produce shale gas from hundreds of wells, spread over a huge acreage. Over the past three years, RIL’s engineers and production staff have been working with frontrunners in the business at Marcellus and Eagle Ford, the two biggest shale developments in the world.

Prices are still low and Ambani is far from achieving his stated aim of generating 10 percent of the overall operating profitability (EBITDA or earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amoritisation) from shale. But the learning makes him one-up over international oil majors as well as Indian rivals like GAIL and ONGC. The next part of the game for most of the Asian companies in the US is to find ways to bring the gas back to India. GAIL, IndianOil and RIL have signed up export agreements to bring back the gas to India as LNG. But there may be many a slip before this happens. Back home in India, the government is getting ready to allow shale gas exploration and production. ONGC and RIL are gearing up to be early movers.

For Virgo Engineers, a Pune-based company that makes valves, the penny dropped about two years ago. The valves made by the Rs 1,000-crore company, are used to control the flow of liquids and are largely used in the oil industry. Its chairman, Mahesh Desai, first came to the United States in 1999 to set up a distribution centre. At that time, a valve made in India and shipped to the United States was 30-40 percent cheaper than the one made in the US, even with the added costs of shipping, customs duty and cost of freight. About two years ago, the cost differential had narrowed to about 20-21 percent. Today, it is almost gone. Much of the reduction has happened because of rapidly rising wages in India and also a supply shortage of engineers to the Indian manufacturing sector. In the US, the wage rates have not increased in the past several years and other input costs have remained stable. “Manufacturing and delivering valves to US locations takes 16 weeks on the logistics side and customers often choose to buy US made valves that can be delivered in just 5-6 days,” says Desai.

Desai and his core team have responded to the changing dynamics and a growing market by increasing manufacturing in the US quite significantly at Stafford near Houston and Oklahoma City. It has two companies, one makes all of its manufacturing in the USA, while the other one too has a significant amount of manufacturing in the US. It has put up 10-15 CNC (computer numerical control) machines and more than 40 people working at these locations. Till 2008, Virgo did not have any manufacturing in the US, only distribution. “There are a growing number of customers who now prefer buying valves ‘proudly made in America’. Therefore, locating manufacturing in the US makes a difference,” says Desai. Today, over 30 percent of Virgo’s revenues come from its US operations.

Shifting gears

The Essar and Aditya Birla groups, both strong players in the metal business in India, have taken a slightly wider view of the US opportunity. Both have focussed on a US-Canada combined strategy to bolster business. Birlas had bought Novelis at the peak of the bull market and turned it around. In 2011, chairman of the Aditya Birla Group, Kumar Mangalam Birla, completed the acquisition of Columbian Chemicals for $875 million to become the world’s largest producer of carbon black. The company now operates from two headquarters in Atlanta and Mumbai. In an interview with Forbes India last year, Birla said shale would lead to a big geo-political shift. Moving towards a target of $65 billion in revenues in the next three years, the Birla team is looking at acquisitions in the fertiliser and chemicals business in the US.

Essar Steel had bought Algoma Steel in Canada (the same town where Jain meals can be had!), to service the demand for the auto industry in the US. The credit crisis shrunk auto demand from 16 million units to about 12 million and Essar’s decision looked ambitious to some analysts. Iron ore for the mill comes from Essar’s iron ore and pellet plant, located across the border in Minnesota. Essar Steel Minnesota has emerged as a major US focussed iron ore supplier. It recently inked a 10-year deal to supply ArcelorMittal US.

Meanwhile, revival is in the air for the US auto big three: Ford, Chrysler and General Motors. Essar Steel CEO Jatin Mehra says, “The US will certainly come back faster than Europe.” Though Essar uses coal (not gas) in the steel mill, Mehra was able to knock 8 to 10 percent off his steel-making cost in 2012. This is because many coal users have switched to gas—causing a huge fall in prices. Mehra expects the falling steel prices to lead to a corresponding fall in car and consumer durable prices—and this, he says, is bound to boost demand.

For Essar, the pick up in automobile demand couldn’t have come at a better time. Essar acquired the steel asset at a cost of $1.5 billion for 4 million tonnes. “The cost was very attractive for us because the cost in steel is roughly $1 billion for 1 million tones,” says Mehra. Essar Steel will benefit but so will many auto component companies who have invested in their US operations.

This is the theme that Motherson Sumi, Varroc and Uniparts have been betting on. Motherson Sumi is the biggest among the three and Uniparts is the smallest. Aurangabad-based Varroc, an automotive part maker with a turnover of $450 million, realised that the demand was slowly coming back and began looking for acquisitions in early 2012. It bought the lighting business of Michigan-based Visteon. The growth in Visteon’s lighting business has given it a huge beachhead in the US market. It has also catapulted an almost-unknown company into the major league in India.

Uniparts’ model has been rather interesting. It is a small company with less than $200 million in turnover. It makes components for off-highway vehicles and farm equipment. Till a few years ago, the cost differential between India and US for the parts that the company made was 35-40 percent.

The difference is now down to 10-15 percent. So Uniparts now offers two options. India-manufactured parts are offered at a lower price but have a longer delivery time. To its US customers, Uniparts offers lower delivery times but slightly higher costs for high-value products. These products are shipped out of the US plants. Soni had foreseen this way back in 2005. When he spoke to customers they said that only 20 percent of their demand would come from low-cost locations. The customers wanted to buy 80 percent from places where adding value was possible. Today almost 50 percent of Uniparts’ revenues come from the US.

Does this mean that US is an El Dorado? It is not, to be sure. There are clearly areas of concern.

There are still major issues around investing. “Putting up new plants is expensive and difficult to execute because of tough environment laws,’’ say several Indian entrepreneurs. This is borne out by the fact that a large part of the investment is in existing (usually distressed) assets that Indian companies have bought and turned around. In the manufacturing business, the other big problem is strong unionisation. Mehra says it was worse when Essar got in. Most agreements with labour were restrictive and allowed little headroom to improve efficiency. Pension and medical benefits for the workforce are often lifelong. If pension funds make losses on their investments, the management has to reimburse it, he says. At Algoma, Essar was able to renegotiate them over the years.

“Today we can sit with the unions and explain to them what is hurting business,” says Mehra. With financial investors, the relationship was often confrontational. We are obviously here for the long term. The next round of negotiations is in July this year. “We have asked for changes and they are co-operative,’’ he adds. Analysts here say recession has brought in some degree of sanity. Birla group HR director Santrupt Misra was able to do the same for Novelis and Columbian.

The other hotly-debated issue that may impact Indian companies looking for energy from the US is the growing opposition to energy exports within the US. The US Senate is currently debating a bill on natural gas exports. Petrochemical and fertiliser companies like Dow Chemicals are lobbying against permissions to export gas, fearing that exports would lead to higher prices.

The oil and gas industry, on the other hand, supports LNG exports to markets in Asia where the price is much higher. The debate is acrimonious and often smacks of resource nationalism. Gas experts like Washington DC-based Bill Holland, associate editor of Platts Gas Daily says, the debate is more in terms of business interests than nationalism.

Twenty gas companies have so far sought permission to export gas (as LNG) to energy-hungry markets like India, Japan and Korea. The Senate is looking at studies that have estimated impact on gas prices. Meanwhile, Indian companies like GAIL continue to forge new agreements to import US gas from the big shale fields. Exports to India are being supported by a lobby that wants stronger India-US relations to improve the US’ strategic balance in South Asia.

Investment banking sources say there is a huge increase in interest from clients in India about opportunities in the US. Cautiously, companies are beginning to look at value deals across the spectrum. For Indian companies, the first decade of the new century was focussed around large investments in Europe. Going by current trends, the second could well turn out to be a pivot to the United States.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)