What Went Wrong With the Aakash Tablet

The disastrous Aakash project has expunged India's dream of developing the world's cheapest computing device. And questions remain unanswered

Imagine for a moment you’re a scientist looking at a stubborn problem—in this case, a mass of a few hundred million poor, uneducated people. To lift them out of poverty, friends who study economics tell you the first thing you ought to do is offer them access to affordable education. And that if you can, you’ll achieve three things. Create a better world; create an incredibly compelling business; and perhaps get a stab at immortality.

There are two ways to go about the problem. The first, you reckon you ought to think through the problem. That means look at the world around you, tinker with ideas, figure what works best, and build a cost-effective solution that eventually helps achieve the objectives stated above.

The second is a pig-headed one. Look at how others around the world are attempting to crack the problem; call in the global media; tell them a tablet-like device with a touch screen can be built and sold at $35; another matter altogether you’ve got no clue how to go about it or why; and then try your damndest best for a stab at glory. In any case, as long as the problem is cracked, who gives a damn?

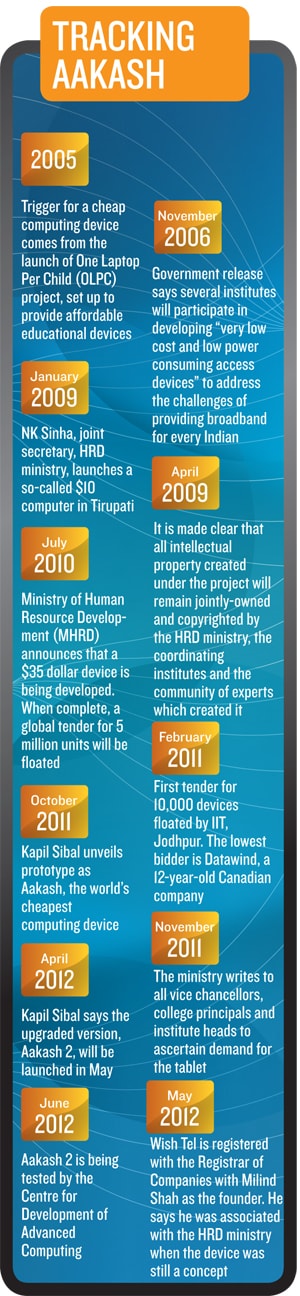

With the benefit of hindsight, it is now obvious the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) chose the pig-headed option. What else explains the fact that almost two years ago, the ministry announced it is in the middle of developing a low-cost computing device for students that would cost just $35? And that when complete, a global tender for five million units of the device would be floated? The blitz that accompanied the announcement had the world in a tizzy.

A little less than a year later, in February 2011, the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Jodhpur, which had taken upon itself the onus to decide what specifications this animal would run on, put out a global tender to build the first 10,000 units. In return for these services, the institution received Rs 47 crore from the government. DataWind, a 12-year-old Canadian company with subsidiaries in the UK and India won the contract, produced a prototype built to spec, and Kapil Sibal, the minister in charge of MHRD, unveiled Aakash, the world’s cheapest computing device.

To put it mildly, the prototype was a disaster. Some phones in the market worked faster than this contraption. The battery couldn’t last two hours if a user tried to play video files on it. The touch screen, well, wasn’t “touchy” enough. And things got ugly between IIT Jodhpur and DataWind. Sibal finally stepped in and in early April this year announced that an upgraded version of the device will be made available by May.

As this story goes to press, we’re in the middle of June. Aakash-2 is still being tested by C-DAC in Thiruvananthapuram; IIT Bombay has been appointed the new nodal institution to drive the project and officials there claim 100,000 units will be supplied for pilot tests by October this year.

On its part, DataWind claims the 100,000 units have already been supplied to the institute. Nobody seems to have a clue what the truth is. What we know is this: Similar computing devices with superior capabilities are being brought out of Chinese factories by the thousands; India seems to have lost the plot; and what could have been an incredibly compelling story is now a stillborn.

The race to build the world’s cheapest computing device started when the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) project was announced in 2005. Headed by Nicholas Negroponte, best known as the founder of MIT’s Media Labs, it was a non-profit entity and funded by global majors like AMD, Google and Nortel among others. The central theme to this idea was to build a laptop that would cost no more than $100.

But Negroponte was not a pig-headed man. He was clear that while keeping costs low was important, it wasn’t the central objective. Instead, it was to make sure technology and resources could be delivered to schools in the least developed countries. He wasn’t hung up on the $100 number. He knew that costs could go up by $30-40 or even $100. For various reasons though, a laptop at $100 was the number that stuck in the minds of people across the world—including NK Sinha, joint secretary at the MHRD.

While the OLPC project has gone through many ups and downs including funders backing out, NK Sinha proposed the MHRD develop a laptop at $10—one-tenth of the price the OLPC had proposed.

On the back of this proposal, in November 2006, a government release said several institutions, including the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and IIT Madras, would develop “a very low-cost and low power-consuming access device to address the challenges of providing broadband connectivity for every Indian, preferably free of cost for educational purposes.”

But N Balakrishnan, associate director at IISc, and Ashok Jhunjhunwala, electrical engineering professor at IIT Madras, say they don’t remember participating in any such project. On the contrary, sources we spoke to say all of India’s best engineering institutes declined to participate in the project because they thought it an unviable idea.

Then like a bolt out of the blue, in January 2009, Sinha announced the launch of the $10 computer in Tirupati. It was met with all-around sniggers because what it looked like was a pen drive with a screen and no features worth talking about. Sinha told us then that some students and faculty members had been working on it for over two years, they had applied for patents and that “…everything need not be told.”

Fact is, until now, everything hasn’t been told and questions remain unanswered.

● What happened to the intellectual property (IP) the $10 laptop project was supposed to generate?

● After the first meeting of the project coordinators, it was made clear “all IP created under the Mission would remain as jointly owned and copyrighted by the MHRD, the coordinating institutes and community of experts which create the IP.” But six years down the line, all IIT Jodhpur can show is that it zeroed in on the specifications, floated a tender and selected the lowest bidder on behalf of the government. What happened in the interim and why wasn’t any IP generated by the institute?

● How did DataWind, with far fewer resources at its disposal than all of the might at the ministry’s disposal, manage to create a tablet that retails in the market under the brand name UbiSlate at a price point much higher than $35? DataWind’s CEO says it was done without using any IP that came from the government-funded project.

Even if one were to be charitable and dispense with these questions, it is impossible to ignore the fact that Aakash isn’t a device that can be used to study on. “The educational experience has to be captured and ought to be central to the design of the entire software platform for the device. I see no such effort. Running a few apps that can show YouTube and a few file formats does not make an educational device. There is no integration of a core idea into the device,” says V Vinay, a former computer science professor from IISc who recently founded LimberLink Technologies to enhance and improve engineering curriculum.

A device that enables ‘studying’ is built differently from one designed for ‘reading’. You can read a novel. But when it comes to studying, say physics, a student ought to be able to read on the device, make notes on it and work out answers to a problem. “Aakash is a disaster,” says a newly retired vice chancellor of one of the largest technological universities in the country. “Without taking a long-term view of the end use of the device…it will remain ineffective.” Ashok S Kolaskar, former vice chancellor of Pune University and KIIT University in Bhubaneswar, calls the content that is being digitised by the MHRD “19th century textbooks in audio and video format.”

If the project has to take any shape, then the obsession with pricing will have to be given up. But it remains sacrosanct. “The price point is the biggest deal,” says a member of the standing committee on National Mission on Education through Information, Communication and Technology (ICT). “It’s one man’s vision,” says Suneet Singh Tuli, chief executive of DataWind. The only problem with the vision: The Chinese have already cracked the price barrier. And for all practical purposes, are close to commoditising the market. Clinging on to an unrealistic price and the ‘Made in India’ tag have ensured the project was stillborn six years ago. What got lost out was an opportunity to rally resources and build a well engineered device.

In contrast to this fiasco is the Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD). For the Socio Economic and Caste Census 2011, it needed tablets in large numbers. It turned to defence equipment maker Bharat Electronics, which had lost the original race to DataWind.

It developed the device in four months and delivered 640,000 tablets in six months to the MoRD, three times the number of tablets sold in the Indian consumer market in 2011. But company officials fear that the unsustainable pricing being demanded by Sinha will keep serious manufacturers away from taking a serious jab at building tablets.

Experts say when the proposal was originally floated, several startups had queued up before Sinha. While on the one hand he encouraged them to come up with prototypes, on the other he discouraged them saying the IITs were developing the devices at a price point of $32. Every time a startup approached him, it was asked to deliver in “two months”. “He had a huge stack of tablets in his room. He’d reel out component prices from Taiwan without revealing much,” says a senior professional who interacted with him.

For startups like AllGo Embedded Systems, a six-year old company founded by ex-IISc students, some “enablement” from the ministry (an indication of commitment to procure) would have helped. But they say Sinha insists vendors cannot buy and supply directly. For the product to meet his standards, it’s got to be assembled locally, which in turn drives prices higher.

Larger manufacturers like HCL Infosystems are watching the drama unfold, albeit from a distance. Earlier this year, it launched a tablet called MyEdu. Though it says it was “never in the race” for Aakash, sources say it backed out during pre-bid discussions due to the ministry’s insistence on keeping prices low. “The idea [of Aakash] was really great; it created a lot of buzz in the market and a lot of confusion in the minds of people as users do look for a brand, support and quality,” says Anand Ekambaram of HCL Infosystems.

Despite several email and phone requests, Sinha was not available for comment. However, academics associated with the project stand by him and argue that the volumes a project of this kind can generate will make up for the low price point Sinha is insisting on. But vendors who signed on to provide laptops at Rs 15,000 each under the chief minister’s ‘one laptop per student’ programme in Tamil Nadu, which aims to distribute 6.8 million machines over five years, are already finding the going tough and have written to the state government that they may find it difficult to sustain their commitments, says Vishal Tripathi, an analyst with research firm Gartner.

“My fear is not so much the money we waste on these pursuits; the Indian government is not known for fiscal prudence in any case,” says LimberLink’s Vinay. He worries about the damage it can do to children. “Instead of giving them the learning they deserve, they get a phony experience as education, which will be tragic.”

In his satirical novel The First $20 Million Is Always The Hardest, a spoof on Silicon Valley of the late 1990s, technology and culture writer Po Bronson took pot shots at the concept of a sub-$300 PC. The plot revolves around a plan to build a low cost device. Much like Aakash, the protagonist in the book Andy Casper sets the rule for his team: The PC has to hit the stores at $300.

The book was published in 1995 when PC prices hovered around $2500. “There was nothing magical about that figure [$300], no technological reason for sticking to that price,” writes Bronson. But conventional wisdom suggested that for a consumer product to reach a critical mass of homes, its price had to match other small home appliances.

When a colleague suggests to Casper that the goal looks hopeless, he blurts: “Stop thinking about the big picture. Just work on one part at a time.” But the outcomes of the prototype sound eerily similar to Aakash. Emagi (electronic magic) as it was called, never looked and felt right. And something always seemed to go wrong with it. Did somebody say prescient?

How Bharat Electronics did it

That was a record of sorts, recalls Mannmohan Handa, general manager of export manufacturing. Handa was pleased with his team, which worked even on holidays, and in three shifts, almost like a “relay race”. “It was not a typical public sector working; [it was a] totally private sector environment.”

Handa’s unit also makes electronic voting machines, but for these tablets, it accelerated the processes, applying all techniques of lean manufacturing, e-procurement and e-testing. Several BEL agencies worked closely to provide application software support for data enumeration, secure data storage, secure data access and transmission. Additionally, it provides foldable solar charging stations and an extra battery pack that lasts eight hours. Handa says this project has opened a new vista for BEL. Will it bid for Aakash-2? That depends on the top management, but the bid should add to the company’s bottom line—near-zero profits aren’t attractive.

(With additional reporting by Rohin Dharmakumar)

Correction: This article has been updated with a correction. In our earlier statement on 2nd page's last paragraph "They say when the proposal was originally floated, several startups had queued up before Sinha" the word 'They' has been replaced with 'Experts' to remove any confusion on attribution of the source of the statement.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)