The Rise And Fall of Jignesh Shah

The 47-year-old entrepreneur, who had taken on institutional forces such as the National Stock Exchange with his commodity exchanges, became a victim of his own break-neck ambition, say close associates. This is his story, one year after the irregularity at NSEL was uncovered

Incarcerated, maligned and painted in every shade of grey: This is not how Jignesh Shah had envisaged his endgame as he plotted his rise and rise in the Indian markets over 15 years, touting the mantra “everything is fair in love and war, and that applies to business as well” to his closest associates with a determined frequency. The scrappy entrepreneur soared and fell by this ambition: In his pursuit of profit, a business associate says, “Jignesh did not see what was for the good of the shareholders and what was good for him. He could not rise to that level.”

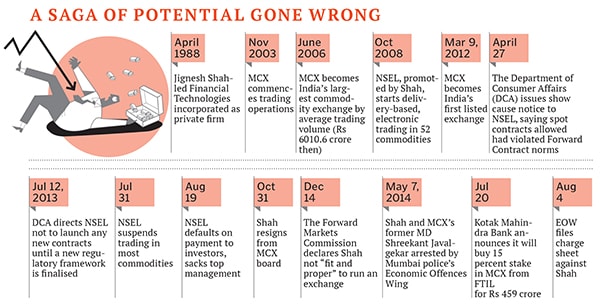

The David who took on Goliaths such as the National Stock Exchange (NSE) started to come undone as serious irregularities at one of his two commodity exchanges—National Spot Exchange Limited (NSEL)—emerged over a year ago. Contracts sold, without the necessary collateral being in place, resulted in defaults and consequent losses of Rs 5,689.95 crore for investors. This led to his arrest on May 7, 2014. With that, Shah ceased to be the textbook iconic entrepreneur who had built an enviable empire and revolutionised commodities trading by taking it online. Instead, he started to make front-page headlines for all the wrong reasons.

Shah, 47, who set up Financial Technologies India Limited (FTIL) in 1988, launched a series of stock exchanges under its aegis in the previous decade, including MCX, a multi-commodity bourse which has become India’s only listed exchange. (It was set up in 2002 and listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange, or BSE, in 2012.)

As FTIL—the holding company which also provides financial markets software to brokers and other market participants—became successful, Shah’s ambitions took him beyond Indian shores. In the space of a few years, he set up exchanges in Singapore, Bahrain, Dubai (UAE), Mauritius and Botswana as well as a financial market content provider, TickerPlant.

“There was everything—the right space, the right vision, technological excellence. And you had Jignesh at the top, driving the group with his characteristic grit and determination,” says Ravi Sheth, managing director at GreatShip India, which has a small stake in FTIL.

The fall, in this context, came even harder. After months of interrogation by the Mumbai Police’s Economic Offences Wing (EOW)—based on criminal complaints filed by investors—Shah was arrested for “not cooperating” with the authorities in the investigation into the events at NSEL in July-August last year.

One year on, just over six percent of the Rs 5,689.95 crore owed to investors has been recovered from the defaulters. At least six different court cases, including a class action suit, have been filed in High Courts of Mumbai and Ahmedabad. And though there is hope that many of the 13,000 investors would get paid in the coming years, there is a strong possibility that the money trail might just go cold.

Either way, the Jignesh Shah story is likely to enter management books as a case study in ambition and potential gone horribly wrong. Repeated efforts—emails, phone calls, text messages—to reach the current management at FTIL and MCX met with no response, but many of Shah’s associates—brokers, friends, colleagues, former staffers—over the last decade-and-a-half spoke to Forbes India, saying that much like his success, his unravelling too was, perhaps, inevitable.

Where He Went Wrong: NSEL

Ironically, and maybe fittingly, among all of Shah’s successes, NSEL, India’s first electronic spot exchange for commodities which started trading in 2008, was foremost. It was a wholly-owned subsidiary of FTIL, whose entire income would be reflected in the parent firm’s consolidated earnings.

In FY13, according to a statement made by NSEL’s former CEO Anjani Sinha to the EOW in October 2013, over 50 percent of FTIL’s profits came from NSEL. The other 50 percent was accounted for by 14 other ventures floated by FTIL.

Shah liked to wear this triumph unabashedly on his sleeve.

In July 2013, a large private equity firm wanted to invest in MCX-SX, an equity exchange started by Shah in 2008, which was being touted as the next big thing in the Indian markets. Many believed it would do better than the BSE, the oldest stock exchange in Asia. It had started attracting investors, one of whom approached a consultant who knew Shah, for the possibility of a stake purchase in the exchange. But Shah was not interested in diluting his stake; instead, he was keen on discussing NSEL.

The consultant asked Shah how he maintained such high volumes on NSEL while NSPOT, the competitor spot exchange promoted by NSE, was stagnating on volumes. Shah smiled and said he simply understood the market very well. “I think we should be able to place our NSEL equity at a valuation of around $1 billion in a few months. I am very confident,” he told the consultant.

He spoke too soon. Within eight days, NSEL hit the headlines with a payment crisis. On July 12, 2013, a letter from the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) raised the question of validity regarding many of the contracts traded on the exchange; this led to a liquidity crunch as befuddled participants now refrained from trading.

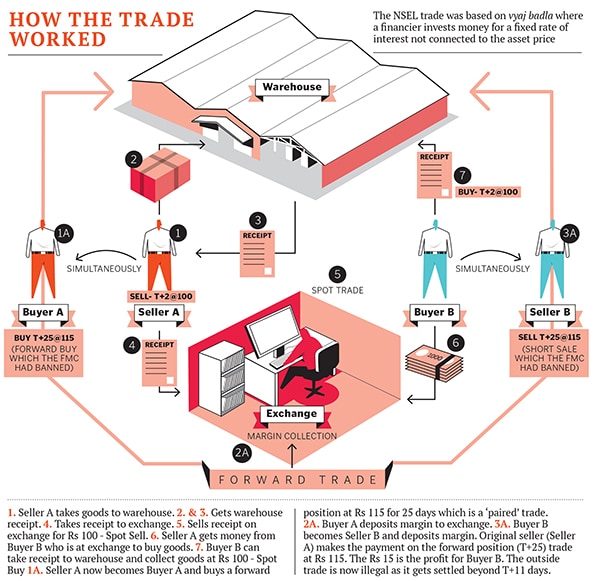

The DCA had granted exemption to NSEL under Section 27 of the Forward Contracts (Regulation) Act and allowed it to trade in one-day forward contracts, provided members did not resort to short sales. “We found that NSEL was violating conditions under which the exemption was given, where several contracts went well beyond 11 days, when the contract cycles should have been a maximum of T+10 [for settlement],” says Forward Markets Commission (FMC) chairman Ramesh Abhishek. In some cases, NSEL also did not insist on ownership of goods in warehouses when sale orders were placed, resulting in ‘short-selling’, which it was not allowed to do, he adds.

On August 3 last year, NSEL informed members that, “in order to protect the interest of clients and public”, trades executed on July 29, July 30 and July 31 had been annulled and reversed. NSEL said it had refunded the pay-in received from members pertaining to these trades. Yet, banks withdrew their credit limits given to procurers on the exchange. It later became clear that there were no goods in the warehouses and that the procurers did not have the money to pay back the investors.

FMC—based on a forensic audit of NSEL by consultancy firm Grant Thornton—in its December 2013 report declared Shah “not fit and proper” to run an exchange and explained the events thus: “Investors simultaneously entered into a “short term buy contract” (e.g. T + 2, i.e. two-day settlement) and a “long-term sell contract” (e.g. T + 25, i.e. 25-day settlement). The contracts were taken by the same parties at a pre-determined price and always registered a profit on the long-term positions.” It had become a financing business where a fixed rate of return was guaranteed on investing in certain products on the NSEL, FMC said in its show cause notice last December.

“NSEL was getting used for a financing tool. That is the core,” says Harish HV, a partner with Grant Thornton.

The problem of regulation was also significant. In India, spot exchanges are to be regulated by state governments but there was ambiguity on which agency should have regulated NSEL. Till 2011, FMC could only seek information from the exchange and had no role in supervising it.

“NSEL operated in an environment of confusion, where it was unclear who had to regulate the exchange,” an associate of Shah told Forbes India. (There are now two national electronic spot exchanges surviving in India; one is the scandal-hit NSEL and the other is NSPOT, set up by NSE’s NCDEX, or National Commodity and Derivates Exchange, in October 2006.)

After the crisis started, the FTIL stock price slid from Rs 750 to Rs 102 on August 29 within 40 days. MCX saw its stock price go to Rs 238 from Rs 800 during the same period.

FTIL has claimed that while it has a common promoter, Shah, it cannot be linked to the NSEL issue. FMC has rubbished this in its 2013 order, saying: “It cannot shy away from its role and duty as a parent company to take reasonable care and exercise prudence in management and governance of the subsidiary company.”

Shah and Sinha were named the main accused. The former has maintained his innocence, saying he was unaware of the events which had unfolded at NSEL. Sinha, on the other hand, first gave a statement that Shah was not in the know of the goings-on at NSEL. However, later, he put the blame squarely on him, saying Shah was getting a weekly update of the NSEL trades and was cognisant of the situation.

Sinha, who had seen similar defaults earlier when he worked with the Magadh and Ahmedabad stock exchanges, was jailed along with Shah, but is currently out on bail.

As for NSEL, it is now virtually defunct. “NSEL, perhaps, was the victim of Jignesh not paying attention while he focussed on the jewel in the crown, MCX, on the one hand, and battled with the system to get the stock exchange licence for MCX-SX on the other,” says one of Shah’s closest business associates.

How He Built The Business

A one-time software engineer who was project-in-charge of the BSE’s online trading system, Shah often called himself a “technology scientist”. He started his career in 1990, in the systems department of the exchange after completing his engineering in Mumbai. But Sinha claims much of his time at the BSE went into trading in stocks.

Shah was still given the opportunity by BSE to study stock exchange technology in London; a few other colleagues were sent to Tokyo and New York for the same purpose. When they returned in September 1993, two of them—Shah and Dewang Narella—submitted a plan to upgrade the technology at the exchange. Their proposal was rejected and the BSE board gave the contract to software firm CMC Limited.

Narella and Shah then moved out of BSE to start their own venture called JCS—which created back-office software for stock brokers—by breaking their three-year bond on January 1, 1995. The duo had to pay a combined Rs 15 lakh as penalty. Shah also invested his own money in JCS while Narella and Ghanshyam Rohira, another BSE associate, joined as working partners.

Shah’s focus was on understanding customers and the business, as well as networking. In terms of the products, he developed a front-end software called ODIN which initially gave them a foothold into—and later a firm grip on—the brokers.

JCS, through a series of mergers, later morphed into FTIL “without going through a public issue of offering its shares to investors”, Sinha says in his statement. ODIN remained the biggest revenue earner for Shah as he attempted to expand in the overseas markets.

FTIL went through a bad patch during the dotcom bust around 2002, but it bounced back after Shah got permission to set up a commodity exchange. With MCX, he decided to take on the NSE-promoted NCDEX, a competitor in the commodities space. He recruited Sinha and Joseph Massey in June 2003 from the Inter-connected Stock Exchange (ISE) promoted by 15 regional stock exchanges. In seven years, MCX became a leader in metals and energy while NCDEX decided to focus on agricultural commodities.

“MCX had tough competition in NCDEX. But due to very aggressive measures taken by Jignesh Shah which included distribution of cash incentives in crores of rupees by him and his brother Manjay among leading broking houses such as Dynamic, Advent and Adroit, it became successful,” says Sinha in his statement to the EOW.

For instance, Shah spotted the opportunity in launching commodity futures which had international prices much before NCDEX did. In fact, he launched his crude oil contracts in February 2005 when it was trading at Rs 2,128 per barrel, almost six months ahead of NCDEX. Oil prices had moved up to Rs 2,553 per barrel by the time NCDEX put up its own oil contracts for trading.

Exchanges offer sticky solutions, which means that once a trader starts on one exchange, he rarely moves on to another unless something goes particularly amiss. Shah had the technology and he was clear that he was going to launch all the trading products ahead of competition so that his traders do not have any reason to complain.

A rival exchange official recalls going to Bahrain to look for business opportunities and being surprised at seeing Shah do the same meetings much ahead of him.

“I do not know how he was able to stay ahead of us in almost every aspect of the game. At times it was frustrating,” he says.

Getting The Right People From The Right Places

‘Applying Population Dynamics Theory on Entrepreneurial Survival Strategy: Case of Financial Technologies and its Promoter’, a 2009 research paper by former Deutsche Bank group senior analyst Ankur Jain and Ram Kumar Kakani, a former professor at XLRI (Xavier School of Management, Jamshedpur), made an attempt to study why a middle-class entrepreneur like Shah was able to achieve what a high-powered and institutional organisation such as NCDEX could not.

“When he started the new venture, Jignesh Shah hired experienced human resources from the market. His top management [at MCX] comprised people who had previously worked with other exchanges. He even hired past officials of FMC, which helped him in establishing cordial relations with the regulator,” the research paper said.

Former FMC chairman Venkat Chary is now FTIL’s non-executive chairman while ex-Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) chief GN Bajpai used to be an advisor to the FTIL group. Another former Sebi official, PR Ramesh, was an officer on special duty at NSEL while former State Bank of India chairman PG Kakodkar was on the FTIL advisory board at one point.

But over a period of time, NCDEX got its marketing strategy right. It started underscoring the fact that MCX was an individual-driven exchange as compared to NCDEX which had promoter shareholders like ICICI Bank when it was set up. Shah sensed that, for once, NCDEX could get an upper hand. He quickly responded by getting Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI) and National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) as shareholders accounting for around 10 percent of MCX.

Running parallel to this competition was NSEL, buttressing the group revenues. Shah wanted to show growth in his parent company and profits from NSEL kept the FTIL shareholders satisfied.

Significantly, Sinha told the EOW that while Shah always hired government employees or ex-bureaucrats for FTIL and MCX, he consciously avoided getting them on the NSEL board.

He was very careful that the NSEL dealings remained in the hands of very few people.

How He Beat The System

Shah was a long-time fan of vyaj badla, a mechanism that allowed an investor to undertake futures trading in the Indian market till it was banned after the introduction of derivatives trading. Vyaj badla allows investors to carry forward a trade as long as there is a financier who funds it for a profit.

Shah spoke openly about how this mechanism of forward trading was killed unnecessarily and he was looking for opportunities to revive it. It follows that after getting permission to start a spot exchange, he sought special permission to use one-day forwards. This, he felt, would help procurers finance themselves as long as they had a product as collateral. The procurers or the sellers would take their product to the warehouses and get them valued. The warehouse receipts, given to them by the custodians, could be traded on the spot exchanges where many buyers (in this case, investors) could bid for them.

Shah’s notion of operating a spot exchange like a forward exchange was a stroke of financial genius. For this, he needed procurers looking for financing and investors who would provide the financing against collateral. “The NSEL management knew that it needed to get small businesses looking for capital to fund this trade,” says Sanjay Kaul, managing director, National Collateral Management Services Ltd (NCML) which handles collateral management for banks and exchanges such as NCDEX and NSPOT. “This gave rise to ‘paired’ contracts (see page 54) which most investors did not fully grasp. They merely understood that they were diversifying their asset allocation into commodities. They were not aware that they were getting into a financing structure for needy procurers.” He adds that many investors did not appreciate the role a collateral management company plays in such a deal. “However,” he points out, “in this case, collateral management was hardly involved probably because there was no commodity that was warehoused or needed to be valued.”

In the case of NSEL, the collateral management was handled by National Bulk Handling Corporation (NBHC), also owned by FTIL.

“NBHC should have been engaged as a collateral management agency to verify the quantity and quality of the stocks,” he says.

“The NSEL as a spot market concept was brilliant, covering the entire ecosystem of commodities. Jignesh did not go wrong with the product, but NSEL taking up the business of managing finance was a fundamental mistake,” says Deven Choksey, managing director, KR Choksey.

Incidentally, NCDEX holds only 5 percent stake in NCML while NBHC, which has now been acquired by India Value Fund for Rs 242 crore, was completely owned by FTIL. “We don’t want to have any conflict of interest with NCDEX and that is the reason why we have such a small percentage holding by the exchange. We also have an exclusive tie-up with NCDEX where we will not offer our services to any other exchange,” says Kaul.

Image: Indian Express Archives / Pradeep Das

Financial Technologies India Limited chairperson Jignesh Shah was arrested on May 7 this year

The long road to recovery

In April 2013, a high-profile investment consultant was asked to put money into NSEL’s paired contracts. He recounts his tale of “desperate” brokers who were trying to lure investors. “They kept calling me, trying to influence me with names of close friends who had already invested money,” he tells Forbes India. “My point was, if there is any scheme which is so safe and secure, why are you following up with me? I should be queuing up to put my money in. I have no sympathy for well-off investors who have lost money. They did not do their due diligence.”

On the other hand, take investors such as this family from Mumbai who lost Rs 6.5 crore. Vijay Ganeriwala, a regular investor in equities, started investing in commodities in 2012 due to the higher returns. “We were told by brokers that this [NSEL’s contracts] would ensure higher returns. It would be the best thing for your children’s future, they told us,” says Ganeriwala’s son-in-law Satish Bangar. “My father-in-law had first invested Rs 50 lakh; we saw interest of 21 percent in the first 15 days. Then within the first month of investment, there was a first default and the cheques stopped coming. But my father-in-law broke all his fixed deposits to place orders here.”

Bangar claims his father-in-law passed away this year troubled by the financial losses. This case is among those that have been filed by the NSEL Investors Forum—the suit includes 2,600 members and a loss of Rs 2,000 crore. Several large and small companies also lost money, including state-run MMTC (Rs 220 crore) and IGL Finance (Rs 125 crore).

Though NSEL is not operational now, its managing director Saji Cherian is confident that investors’ funds will be recovered. “The complete money trail is available and agencies have attached defaulters’ assets to cover a large part of the investors’ money,” he told Forbes India. NSEL has now received a show cause notice from the government, asking why the exemption granted to it in 2007 should not be taken away. Cherian wants it to stay till the crisis is resolved. There are only 40 employees left on the rolls of NSEL apart from consultants involved in legal matters and recovery of funds.

Brokers who sold the product say they were not aware of the problems. “No broker will put his client’s money in a risky investment,” says the head of a leading brokerage firm whose clients lost money in the scam.

But, at the same time, many brokers had also purchased the NSEL product from their proprietary accounts. “Nobody thought Shah would get trapped,” says an investor.

What Next?

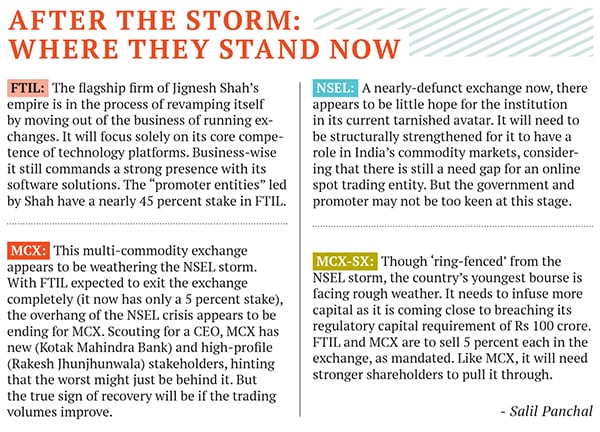

Last month, Kotak Mahindra Bank announced that it would buy 15 percent stake in MCX making it the single largest stakeholder in the company; high-profile investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala has also raised his stake to nearly 3.5 percent through the open market. Jhunjhunwala has probably taken note of the fact that MCX still commands an 85 percent trading market share amongst leading commodity exchanges.

After the Kotak deal, FTIL’s stake in MCX would stand at just five percent which, an exchange insider says, “significantly lowers” the risk the commodity exchange faces of not getting approval from FMC to launch new trading contracts beyond August and also for its 2015 calendar.

Shah’s own future remains even more uncertain. Like all conflicted stories, his too doesn’t have a clear ending. None of the money from the NSEL fraud has yet been traced to him and he has appealed against the FMC’s “not fit and proper” order in court. (Shah’s own scheduled appeal for bail did not take place on August 11.)

His fate still hangs in balance but one thing is clear: As and when he gets released, he will have to stay clear of all regulated businesses. And he knows that well. Before going to jail, Shah had indicated that FTIL would completely move out of exchange-related ventures and remain a pure technology company. “I will concentrate on something new,” he had said.

A close associate says that is the only way forward for him. “Jignesh should focus on his core competence of technology and not get into the running of exchanges. He needs to fix himself... although he has a sharp mind, he has faith in a lot of people. When you run large complex organisations, one has to know whom to trust, when to trust and how much to trust.” However, the question now for Shah is whether he can regain trust from the business community.

“Everybody has two opinions about Jignesh Shah, not just one, which is the most unfortunate part,” points out Anil Singhvi, chairman, iCAN Advisors, who is also an advisor to the FTIL board for its stake sale. But this duality in opinion can also prove to be his saviour as the jury, literally and figuratively, is still out on the man who dreamt too big.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)