Restructuring the Planning Commission

A crack team led by Arun Maira is trying to breathe new life into a fading institution

In the fourth weekend of October, about 150 officials of the Planning Commission gathered at the PUSA Institute campus in New Delhi for a three-day workshop to discuss 40 major issues confronting the country. There was open and heated debate on issues such as employment, agriculture and energy.

The discussions were structured in such a way that by the end of the sessions, everyone had spoken to one another on every issue.

The experience was nothing like the everyday ping-pong of dreary files. Until then, nobody had asked the scores of officials their opinions on issues like innovation or skill shortage. It was the first time that the bureaucratic behemoth’s collective intellect was put to rigorous use in the planning process.

“This is the best time I have had in the Commission,” one official gushed. At the end of the consultative retreat, the team identified 15 issues, including employment-led growth and making markets work for the poor, as the most important and immediate ones. The Commission’s top brass will now whittle the list down to about 10. These will form the basis of the approach to the next Five Year Plan. It is a fresh start.

A year ago, the idea of reforming the Planning Commission took root once again. The objectives are formidable: The sleepy old institution will be resurrected as an organisation with cutting-edge ideas that can sense and respond to India’s long-term challenges. And the man in charge of the process is Arun Maira, the former chairman of global consulting firm Boston Consulting Group in India and now a member of the Commission.

The Planning Commission’s primary role was to allocate resources to the Centre and states. But over the years, the states had become practically disconnected from the central planning process. Bimal Jalan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, points out that the process was no longer integrated because there were different governments in different states and the tenures of the state governments were also different.

As the Congress Party started losing in the states, giving way to alternative ideologies, Plan priorities at the state level began to get dislocated from the Centre. As a result, the annual plan became more important than the Five Year Plan.

By and by, state inputs into the Five Year Plans became perfunctory. According to one state official, interactions with the Commission had become mere “formalities” as allocations were decided even before interacting with the states.

The disconnect has widened so much that the Commission and the finance ministry practically decided the Plan with hardly any analytical understanding of the various dimensions of major issues such as water management or basic healthcare across the country.

Lack of consultation meant preparing the approach to the Plan was practically a solitary job. “The problem was there wasn’t much of a process,” says Pronab Sen, a veteran of the past three approach papers or the guiding documents for Five Year Plans that have been the centre-piece of medium range economic planning for the past six decades. Usually, Sen and a few officials would scan mid-term appraisals to pick up issues, get it approved by the internal planning commission and write it out. It was then put out for consultations with departments. The changes, if any, were usually incremental.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman of the Commission, has an interesting anecdote about the late Raj Krishna, economist and former editor of the Economic and Political Weekly. Someone asked Raj Krishna what does the approach to the sixth Plan look like. “This is not the approach to the sixth Plan. This is the sixth approach to the same plan,” Krishna said, succinctly describing the rut into which the Commission had fallen.

In many ways, Maira’s job is to reclaim the original mandate of the Planning Commission: To assess and allocate resources in the most effective manner; determine priorities and indicate factors that could hold back economic growth; and determine conditions in the given socio-political environment for successful execution of the Plan.

The Beginning

One evening in October 2009, Arun Maira got off a plane at the Delhi airport and switched on his cellphone. The message box was full with texts from journalists asking Maira about his new role at the Commission. While he was up in the air, deputy chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia had announced that the panel was restructuring itself into a Systems Reform Commission and that Maira was in charge of the recast.

Though Maira was a bit anxious about his sudden anointment, he finally understood his purpose at the Planning Commission. He recalled Ahluwalia telling him when he had just joined the Commission as a member: “You will be highly frustrated in this place. Here nothing works. It is so hidebound. It is a challenge to get things done.” However, while trying to figure out his own role in the Commission, Maira had already begun thinking about change and had been talking to his colleagues about it.

There is an essential difference between Maira, who, as advisor to the corporate world, is trained to focus on solutions, and rule-bound bureaucrats, who instinctively keep clear of problems. In true corporate style, Maira had to get out of his windowless office at Yojana Bhavan to think out of the box.

So around Eid last year, when colleague Syeda Hameed suggested a corporate-style offsite, Maira readily agreed. The idea was to introspect — on the Commission and their own careers. They could not go to a hotel or more picturesque location because the government was on an austerity drive, so they went to another office complex at Lodhi Road in Delhi. As they talked, one thing became clear — they all wanted to have an impact on the least included and least privileged India. Frequently, they also worried about being effective in a coalition-driven political environment where the government has to also work through the federal structure. The discussions spilled over to the panel’s internal meetings every Friday.

Two Fridays later, at the internal meeting when members were again venting their frustration on the Commission’s functioning, deputy chairman Ahluwalia said that he had mentioned to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who is also chairman of the Commission, that they were having these existential debates. Singh thought that Maira, who was a “management type, could help”. Then Montek looked at Maira and said: “All your colleagues want you to do something. You are an expert at this. You do something.”

“[Earlier,] I had questions on my mind about my role in the Commission. I recalled my conversation with Montek. It all began to add up,” says Maira.

The Plan

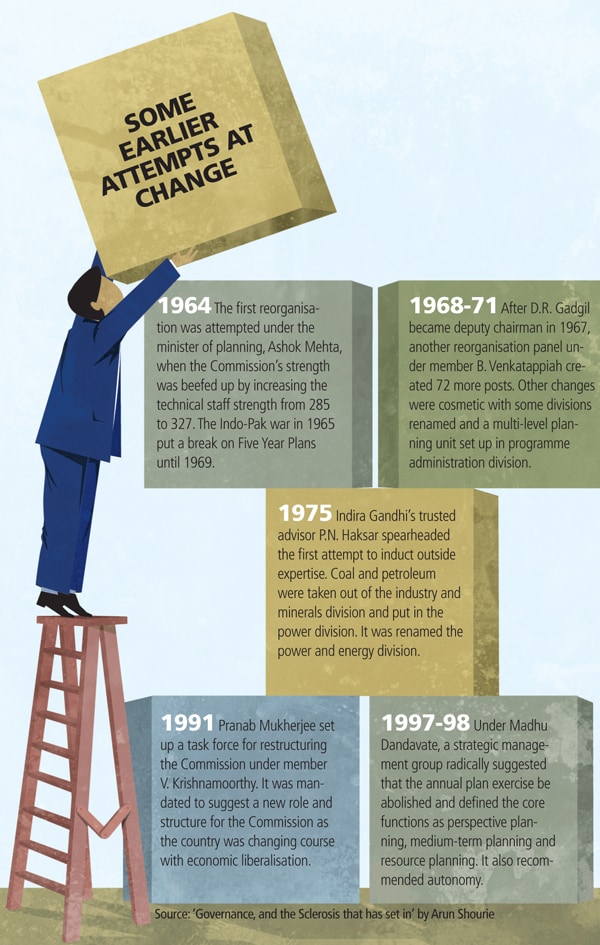

As he spoke to more people, Maira understood that he was not the first one to attempt a reform of the Commission. There was a consultant who had been engaged during the Vajpayee government but nothing came out of it. He had a word with N.C. Saxena (currently a member of the National Advisory Council), who was in the know and met consultants to understand what happened.

On digging deeper, he found that though the staff was engaged with the idea, deputy chairman K.C. Pant was cool to it. Even the then Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee was agreeable, but Pant never took it up with him. This was why Maira decided to bring the sponsors of the project on board early on.

Maira and Ahluwalia drew up a diverse list of 20 names, which included a mix of industrialists such as Ratan Tata and Kumar Mangalam Birla and seasoned bureaucrats such as C. Rangarajan, Bimal Jalan, Vijay Kelkar and Vinod Rai. In one-to-one sessions with them, he asked two things: Should there be a Planning Commission? If yes, what should be its role?

The first reaction from many was, “shut the damn place”. But as Maira persisted, what he clearly saw was that most had issues around the way the organisation was functioning.

Bimal Jalan says that the Planning Commission is the only body which has inter-ministry knowledge and believes it has a very important role at the central level. However, Jalan feels that the times have changed and merely allocating resources over a five-year period is not enough. He expects the Commission to play a more focussed role.

“If you want to make anything effective at the central level, you have to cut across ministries. The Planning Commission could be that institution which becomes the monitoring agency for implementation,” he says.

N.K. Singh, former member of the Planning Commission, told Forbes India that the biggest problem is that it is a very powerful organisation without

accountability. For example, he points out, that the deputy chairman, who effectively heads the Commission and influences a major chunk of government expenditure, could never be questioned directly in Parliament.

Ahluwalia says that even if the Commission were to be disbanded, somebody would have to do its main functions of allocating resources, designing policies and evaluating performance. According to him, that would require as many staff and as much resources that the Commission has today.

As Maira spoke to more people he could see that they agreed there was indeed a role for the Commission. A multi-party government and federal structure required a set of people who are non-political thinkers and were able to foresee what was happening. Many said it was even more relevant today than it was in the past.

“To be able to foresee in that storm and show the channels and challenges is necessary for the pilots to navigate,’’ says Maira.

The Commission then presented the inputs to the Prime Minister over three meetings. He suggested that the challenge was to get many ministries to work together. He wanted the panel to be a Systems Reforms Commission. “How people see us is important. PC should be an essay in persuasion,” Singh told them.

The Preparation

Many people who understand the organisation well advised Maira to not tamper with the structure. “Start with the purpose,” they told him. So Maira asked people to envisage an organisation they wanted. Then they would work to re-engineer the processes, leaving the structure untouched, to achieve that objective.

“Our problem is we talk of marriage before courtship. It is very early to say how it is going to turn out,” says member and veteran bureaucrat Sudha Pillai.

Small beginnings are being made. For example, there was unhappiness among older members with the quality of interaction with the chief ministers. Some members offered to rework the process.

“We realise we are not very good at doing it and need to work on it. But this is something that even the CMs would be happy to know,” Maira says. Such interactions could be used to guide the finance ministry in state policies. States recognise the change, although they reserve judgment until the eventual impact on allocations in the next Plan is known.

N. Baijendra Kumar, principal secretary to the Chhattisgarh Chief Minister, says that there is a distinct shift in the way the Commission engages with the states. “The interactions with the Commission are more serious and frequent now. It is clear that they are keen to understand the states’ point of view. They even send teams to experience first-hand the key developmental schemes and issues [such as Naxal violence] that affect the state.”

Such consultation becomes all the more important as the number of stakeholders and complexity of the process increases. For instance, child malnutrition is a subject that touches four-five ministries, state officials and anganwadis. Led by member Syeda Hameed, the Commission organised a meeting of all the stakeholders, including NGOs, in one room to discuss and arrive at some kind of action plan to tackle it. It was the first time Hameed was doing something like this.

To help, Maira dipped into his network to organise a coach who could help facilitate the dialogue. Now, they have enlisted about 20 coaches. Ministries are being rated and they are now looking at ways to recognise inter-ministerial collaboration and co-ordination. Shared goals are being set out.

Approach to the Approach

The first big change the Commission is trying out in its main mandate is in the preparation of the approach paper for the 12th Five Year Plan. This time there is an “approach to the approach paper”.

Consultation will precede, not follow, the draft approach paper. To figure out the key challenges across the various sectors of the economy, the Commission has identified 34 sectors such as health, women, growth strategy for agriculture, rural infrastructure, skill development and so on. Each was explored across 10 systemic factors such as citizens’ expectation, markets, governance and institutions, science and technology and so on — creating a matrix with 340 cells.

Before the weekend consultative retreat, the team had shortlisted 40 key challenges after analysing the broad systemic problems identified in the 340 cells. The idea of the approach to the approach was also run past about a dozen thought leaders such as Nandan Nilekani, Anu Aga and Renana Jhabvala of the Self-Employed Women’s Association.

According to the new plan, Ahluwalia has sent out letters to the chief ministers sensitising them of the process and letting them know that the Commission will shortly be getting in touch for their views on specific issues. It will not just be the state governments — different stakeholders such as civil society, bureaucrats, industry, college students, academicians and local officials will be part of the discussion process too. Commission members would lead the discussions. A new Web site is already up and running soliciting suggestions and feedback.

Many Minds at Work

It was not easy to cut through the inertia of years, however. Scepticism abounded, outside as well as inside. Project managers protested that the approach paper was not done this way. The protests were, however, brushed aside by the weight of experience.

Pronab Sen, who had done all the previous three approach papers, backed Maira. “What you are suggesting is not just required to be done. I know all the difficulties why it can’t be done. And I would like to help,” Sen told Maira. That silenced most critics.

The enthusiasm spread to others too. S.P. Seth, principal advisor (administration) transferred the entire project co-ordination team to Sen, removing the need for authorisations that would only cause delays. A steering committee of Maira, Sen and Seth now keeps watch on the progress of the approach.

The quality and timing of consultation is the big change in the process. Amitabh Behar is the convener of “wada na todo abhiyaan” (do not break your promise campaign). It began in 2004 when the Prime Minister said he would not make new promises on Independence Day but would strive to keep the ones made in the common minimum programme of the UPA’s first term.

Representing a large number of NGOs under the national social watch coalition, Behar has told the commission that the NGOs in the coalition will collect feedback from the grassroots on various issues that the approach paper shortlists. Behar believes that it is a refreshing approach. “Whether this will translate into something concrete is a million-dollar question,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)