Project Monitoring Group: The Breaker of Deadlocks

It may have no authority over clearing projects, but the Anil Swarup-led Project Monitoring Group has helped prevent logjams

One July day in 2013, a group of officials sat around a large conference table in Room 264 of Vigyan Bhavan Annexe in Delhi. They were discussing the fate of the Delhi Aerocity, a 43-acre hotel hub near the Indira Gandhi International Airport. The project, originally scheduled to be completed for the Commonwealth Games in 2010, had been hanging fire because security agencies were prickly about runway-facing windows.

The deadlock was broken by a slight, bespectacled man chairing the meeting. This year, suggested Anil Swarup, additional secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat, let the prime minister deliver his Independence Day speech from behind a brick wall [instead of the usual glass enclosure]. If the PM is not safe behind a glass partition, he pointed out to his startled audience, nothing else would be. Point driven home, the Defence Research Development Organisation was asked to develop specifications for bullet-proof glass for the windows concerned. Within months, three hotels were ready to welcome guests.

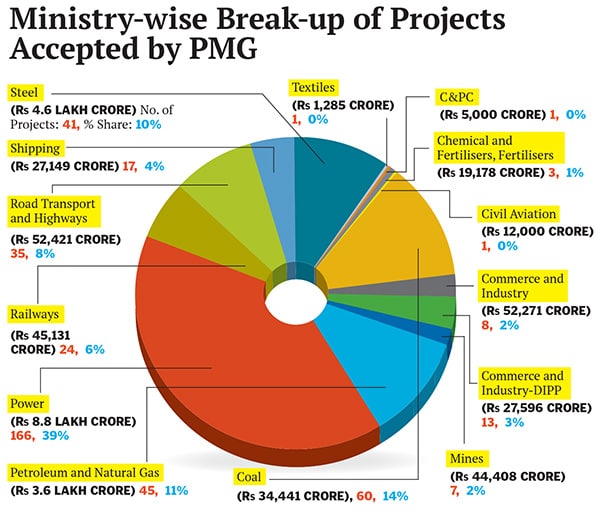

Ten months later, 55-year-old Swarup, a 1981 batch IAS officer, has wrestled with far more complex issues holding up much bigger projects. The Project Monitoring Group (PMG), which he heads, has helped 153 projects—entailing a total investment of Rs 5.76 lakh crore—get going. These projects had been stuck for various clearances, some of them for years. “Given the brief he has, Swarup has done an outstanding job,” says Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman, Feedback Infra, an infrastructure consulting, engineering and O&M company. “It couldn’t have been easy, with the huge degree of political pressure, huge expectations created among domestic and international investors, the extremely short time he was given and the complex nature of the issues he had to deal with.”

The PMG was set up in July 2013 as a secretariat for the Cabinet Committee on Investments (CCI), which itself was a mechanism to unclog a colossal number of stalled investments, mostly in the infrastructure sector. By early 2013, it was estimated that projects with investments of Rs 22 lakh crore were logjammed. Project promoters began defaulting on debts, and banks started piling up bad loans. A study by Axis Capital shows that bad loans and stressed assets of banks rose from 3.4 percent of total infrastructure loans in FY2011 to 17.4 percent in FY2013. Worse, the scenario scared prospective investors away. Between FY2009 and FY2013, the study notes, new project investments showed a negative CAGR of 32 percent.

Industry had been flagging the issue for nearly three years, says A Didar Singh, secretary general, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Ficci). Individual industrialists too had taken up the matter with senior ministers and officials. The Planning Commission, says then Deputy Chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia, was the first to ring the warning bell. The Commission had been tracking, since 2010, the quarterly progress of annual targets set by six infrastructure ministries. Reports on these were going to then prime minister, Manmohan Singh.

But it was only in 2012, after economic growth began to falter and leading industrialists from the power sector met Singh, that the problem was addressed seriously. Pulok Chatterjee, the then principal secretary to the PM, started holding regular meetings to push infrastructure projects. The Twelfth Five Year Plan recommended the setting up of a National Investment Approval Board (NIAB) headed by the PM to speed up large infrastructure projects. It suggested the Transaction of Business Rules be amended to allow NIAB, comprising key ministers, to give statutory clearances to projects more than a certain size.

At a National Development Council meeting in September 2012, former finance minister P Chidambaram pitched for a National Investment Board—the NIAB with a different name. In December, this became the CCI, with the mandate to clear projects worth more than Rs 1,000 crore. But the problem required more focussed attention than ministers meeting once or twice a week. It also turned out that decisions taken by the CCI were not being implemented. Chidambaram then suggested the PMG as a secretariat, which could do the groundwork for CCI meetings and resolve purely administrative issues, as well as monitor the implementation of CCI’s decisions.

Swarup was driving the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana—the health insurance scheme for the poor that has wowed international lending agencies—and was due to return to his Uttar Pradesh cadre. But he was given a year’s extension and put in charge of the PMG in July. The work was not entirely unfamiliar to him: He had done something similar in 1993 in Udyog Bandhu in Uttar Pradesh.

With lists of projects being thrown at him, Swarup got down to work. The priority was to set up an open, transparent mechanism of functioning. A team in the Cabinet Secretariat worked round the clock to develop an online portal, which went live within a month. All projects are to be registered on the portal, along with details of the problems they are facing. Only then would the PMG take cognisance of them. Once the project gets a docket number, the problems are automatically sent to the relevant ministry or state government, where an official must respond on the portal itself. There is no physical movement of files, no scope for excuses for delays, and no verbal orders. “This is a file-less office,” Swarup beams from behind a desk with a few sheets of papers.

Regular meetings with project promoters are held to thrash out issues. The PMG has 12 sub-groups aligned with different ministries, three of which meet once a week. Every Monday and Friday, Swarup heads to a state capital to hold similar meetings there.

“There’s a spirit of cooperation at these meetings; the focus is on finding innovative solutions,” says Ajay Bhardwaj, COO of Sterlite Grid, a Vedanta Group company whose three transmission systems projects were delayed. Updated information on the portal ensures meetings are focussed and productive.

Swarup himself comes thoroughly prepared. “He does a lot of cross-checking of both claims and blames. That makes finger-pointing and buck-passing games difficult,” says AK Tandon, director, corporate affairs, Hinduja Group India. Officials, though, complain of his brashness. “Until we call a spade a spade, we will never find solutions to a problem but will only push them under the carpet,” Swarup shrugs.

He brings two strengths to the job, says Ficci’s Singh: His ability to come up with creative solutions; but more important is the backing of the PMO and Cabinet Secretariat. Chatterjee kept track of the PMG’s progress, with Chidambaram and the PM getting quarterly and monthly updates respectively.

There are complaints that Swarup browbeats officials into taking decisions. When two public sector banks dragged their feet on a corporate debt restructuring package that 26 other lenders had agreed to, Swarup is reported to have hinted that an enquiry would perhaps be needed to find out if either of the two groups was influenced by extraneous considerations. By the next meeting, the problem was resolved. It’s a delicate balance that Swarup has to strike, says Bhardwaj, keeping project progress on track, while mobilising the government machinery into action.

Does the PMG encourage circumventing of procedures to ensure results? No, says Swarup. “My mantra is just one: Follow all processes, but don’t delay either a clearance or a rejection,” he says. “A rejection will need a reason; if the company is not satisfied, it can approach an appellate authority. But tell them upfront.” Some gas-based power plants complained that they had not got fuel linkages. At a meeting, it turned out that there was no domestic gas available. The matter ended there, he says.

Technically, the PMG doesn’t have the authority to clear projects. But, Ahluwalia notes, by giving visibility to the fact that a project has problems, by identifying the ministries and departments that are causing the problems, the transparent online system has created an environment where problems get solved. Those stalling clearances on specious grounds stand exposed. “That was an extremely smart thing to do; it sets out a transparent audit trail,” says Shailesh Pathak, president, corporate strategy, Srei Infrastructure Finance Ltd. It also ensures that the PMG’s success is not centred around one individual. “It is a fantastic organisational structure,” says Nitin Idnani, executive director, Axis Capital.

Those in the know say Swarup initially faced a lot of resistance from within the UPA government. He refuses to be drawn into this, pointing out instead that ministries that were earlier a bit wary are now seeking PMG’s help in dealing with other ministries. “There has been a tremendous buy-in of the process, as people came to understand the value of what we are doing. Some ministries moved from total reservation to total acceptance.” State governments, too, are enthused by the idea—14 of them are setting up their own PMGs.

The PMG started with 60 projects; now it has 543 on its plate, 423 of which have been taken up for resolution. Problems relating to environment and forest clearances dominate. Thanks to the groundwork and filtering PMG does, only matters requiring policy changes go to the CCI, which has dealt with only 18 cases since PMG was set up.

Opinion is, however, divided on whether all this has led to a buzz on project sites. It hasn’t, says Feedback’s Chatterjee, while Swarup says it has. Work has started in 113 cleared projects, totalling Rs 3.7 lakh crore, he insists.

Sure, the PMG hasn’t resolved all issues projects face, and cleared projects have to contend with other hurdles. Idnani’s report shows that though the PMG’s intervention will add 25 GW of capacity between 2013 and 2017, projects worth 12 GW still face issues that it cannot resolve—law and order issues in Maoist strongholds, land acquisition hurdles, inadequate support infrastructure and procedural problems. If projects face additional issues, they can come back to the PMG, says Swarup.

The business chambers are cheering. The Confederation of Indian Industry has asked the threshold to be lowered to Rs 500-crore projects, while Ficci wants it even lower at Rs 100 crore projects.

Not everyone wants to go to the PMG, though. Hemant Kanoria, chairman and MD of India Power, has two power projects in West Bengal that were getting delayed. One got sorted out through normal channels; the second is awaiting coal linkages. Kanoria prefers to tackle things at the level of the administrative ministry itself. “The ministries need to be strengthened and told to put their systems in place. Why not just keep guidelines and systems simple, instead of setting up committees and adding another layer to resolve complex issues?” he asks.

Singh agrees: “If someone needs environmental approval, the environment ministry should give it. Why should the Cabinet Secretariat summon people to get it done?” Even as Chatterjee praises Swarup, he feels the PMG is not the right intervention. “This is an immediate, jugaad response to the late realisation of a crisis. India needs a long-term sustainable institutional answer to logjams. Why have obstacles in the first place?” That’s something Ahluwalia endorses. “We need to reform our regulatory processes radically,” he says.

The new government should mull on that, perhaps.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)