Maxx Mobile: The Shanzhai Warrior

Ajjay Agarwal's Maxx Mobiles is among the clutch of upstarts that used off-the-shelf technology to erode Nokia's dominance in India's mobile phone market. Will the tribe survive the perils of scale?

In 1992, Nokia — already a $3.4-billion company with over 26,000 employees — launched the world’s first GSM phone and made Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo executive vice-president and chief financial officer (He become its CEO later).

The same year, 6,000 kilometers away in Mumbai, the Children’s Academy school decided to fail 14-year-old Ajay in 9th standard. His marks were too poor and Ajay’s teachers wanted him to repeat a year in the same class.

But the boy had other plans. He simply dropped out.

“I knew I was average at studies and didn’t see the point in continuing. But I was very fast in calculations and was passionate about large volumes,” he says.

Soon, he joined his father’s electronics trading business, diving headlong into a world filled with cordless phones, calculators, air-conditioners and televisions on the one hand, and duties, taxes, commissions and profit margins on the other.

“I would sell off entire consignments meant for retailers to wholesalers, just because I wanted to earn back the money quickly. My father would scold me for that,” he says.

In 2006, he added a second J to his name following the advice of a numerologist, becoming “Ajjay”. Today the 33-year-old with two Js is giving hell to the company led by the man with two Ls in the world’s fastest growing mobile market.

Ajjay Agarwal’s Maxx Mobiles is now the fifth largest mobile brand in India with a 4.7 percent market share.

And he’s just getting started. “When we do the things we plan, people will be shocked,” he says.

The Band of Upstarts

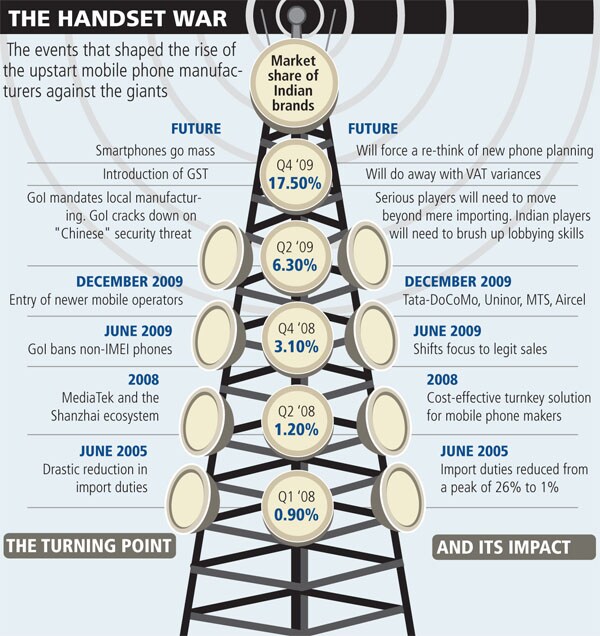

The rise of local brands like Maxx, Micromax, Spice and Karbonn is arguably one of the fastest shake-ups the world has seen in a category that was both mature and dominated by well-entrenched brands like Nokia, Samsung and BlackBerry. In about two years, these newcomers have gone from under 1 percent of the Indian mobile handset market to 17.5 percent, collectively selling over 2 million phones every month.

Their rise was facilitated by a combination of domestic factors: The reduction in custom duties on imported phones to almost zero, the Indian government banning cheaper grey market phones from China that did not have IMEI numbers and the rapid addition of new mobile connections in India brought on by the entry of newer mobile operators.

But an equally important factor was the growth of a Taiwanese firm MediaTek that offers a platform for these brands to create ever cheaper mobile phones crammed with features. In China, MediaTek’s software is known as the platform of choice for hundreds of electronics companies that sell cheap-yet-functional knock-offs of well-known products, or Shanzhai.

MediaTek realised quite early that the huge difference between manufacturing costs and selling prices for well-known phone brands — like Nokia — was not sustainable. So it cobbled together an integrated design-plus-hardware offering that allowed upstart entrepreneurs to literally dream up their own phone designs by mixing and matching off-the-shelf components.

Overnight, mobile phone technology went from being a differentiator for the Nokias, BlackBerrys and Samsungs of the world to a commodity available to anyone with a ticket to Beijing and a cheque. “We’ve moved away from a world in which the global phone companies romanticised their technology edge over smaller or domestic competitors. Today, it’s very hard to find a feature that can’t be replicated by the domestic guys,” says Naveen Wadhera of private equity firm TA Associates that has invested $45 million in Micromax – the largest of the domestic brands.

In fact, the pendulum swung so far that innovation began to be led by the newer players. Unrestricted by global supply chain, brand or regulatory requirements, they could create phones for customer needs that a big company like Nokia would consider too niche or transient. Dual- and triple-SIMs, phones claiming 30-day standby or AAA-batteries, GSM-CDMA combos, 12 megapixel cameras, alphabetically-arranged full keypads… Name it and some entrepreneur has already launched it.

“Buying a phone today is almost like buying a disposable razor,” says Ajay Relan, founder of the $500 million private equity fund CX Partners that is now studying a few of the new Indian players. “Why should I buy a higher-priced Nokia if I know in 1-1.5 years it will become obsolete and something newer, sleeker and with better features will come around? Why do I make an investment in an expensive product?”

0-100 in 2 Seconds

In 2004, after importing mobile phone batteries and chargers from China for seven years, Agarwal bet against the trend and decided to start manufacturing them in India. He opened his first factory in Mumbai, then a second one a year later in Haridwar, followed by a third in Mumbai in 2009. “The stuff I was importing from China had quality issues, which because of my warranty policy, hurt me,” he says. Today, Agarwal’s three factories with a combined capacity of 80 million batteries and 37 million chargers have made him the largest player in that space, earning him a post-tax profit of nearly Rs. 80 crore on revenues of Rs. 440 crore last year. He claims that this year he’ll more than double those.

The success of his mobile phone business is even more rapid.

Infographics: Hemal Seth

In April 2008, he started planning his move into the Indian mobile handset market, betting on the cash flows and distribution reach provided by his accessories business as leverage for growth. It is a testament to the Shanzhai ecosystem around MediaTek in China that within just six months, Agarwal had 11 models of “Maxx” branded phones which he started selling through his accessories distributors in Mumbai.

By June of 2009, Agarwal had put up company-owned branches in 21 states in spite of selling just 3,000 phones in April. He went against the advice of his team members on investing so aggressively before having the revenue to sustain it.

“I believed that we should hit pan-India,” he says, “so I took the risk.” The expansion cost a lot of money. He compounded that by buying expensive airtime during the Twenty20 cricket World Cup to air his as-yet unknown company’s first advertisement. In hindsight, it was a risk worth taking.

The visibility of the advertisement and an aggressive reach-out from his staff helped Agarwal sign up nearly 500 distributors in just two months. His sales began to zoom shortly thereafter.

From 3,000 mobiles in April, Agarwal went on to sell 50,000 in June, 95,000 in August and 300,000 by the end of the year. Research firm IDC India says Maxx had a 4.7 share of the January-March 2010 mobile handset market in India of over 36 million handsets. Maxx’s revenue during that period was Rs. 454 crore, including its accessories business, says Agarwal. He wants to take that to Rs. 3,000 crore by the end of the year.

To do so, Agarwal is turning to private equity investors, like his bigger and better-known competitor Micromax did earlier this year. In March, he took in a $20 million investment from Singapore-based Star Holdings.

Back in India many well-known private equity funds are currently evaluating Maxx, scratching their heads to understand how a 14-year old school dropout built a Rs. 2,000-crore business so quickly. And if they can hitch a ride on his journey to make some money in the process.

A Giant Stumbles

Much of the market share gained by the new mobile handset companies in India has come from the leviathan Nokia, the big daddy of mobile phones. At one point the company had an unheard of market share of nearly 70 percent in India. But thanks to a combination of lethargy on its part and nimble-footedness from the newer brands, that share is down to 54 percent, according to IDC India.

The best example of its inability to react to changing market conditions can be gauged from its dual-SIM strategy. These phones that have been around since 2007 became one of the most in-demand features during the last two years as Indian mobile users tried to profit from the tariff wars between operators without having to change their number frequently. Yet Nokia took till June this year to introduce its first dual-SIM phone.

The newer brands also turned one of Nokia’s strengths — a massive distribution network driven by large volumes — on its head. “Nokia became an over-distributed product, with new outlets selling their phones coming up every day,” says Sanjeev Naswa, a director with a Delhi-based distributor of mobile phones, Digilogic Infosystems, which was the first “Nokia Priority Dealer” and “Nokia Care Center” in north Delhi.

As the number of outlets selling Nokia phones exploded, the average volumes per store started falling. Because making money from Nokia phone sales had always been a volumes game – the company usually gives 2 percent of a handset’s price as “margin” to a distributor or retailer — this hurt many phone retailers a lot.

“Many of them were forced to become multi-brand outlets while the quality of newer dealers went down drastically,” says Naswa.

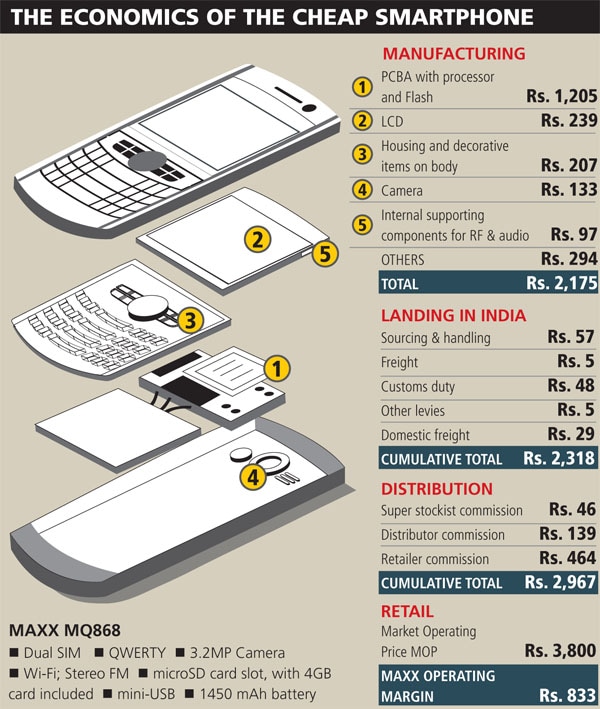

In contrast, the newer brands offered margins ranging from 10 to 20 percent of a phone’s value to dealers. For instance, Maxx will offer its dealers 20 percent margin on the sale of each MQ868, a Wi-Fi enabled QWERTY phone it plans to launch in September. In addition, distributors and “super stockists” will get 6 percent and 2 percent respectively.

Even when Nokia tries to counter such strategies by offering higher margins, its volume-driven sales organisation tacks on additional sales targets in the process. “Their revised sales targets become so aggressive that you cannot make more profits even with higher margins,” says Naswa.

But Nokia is fighting back now.

V. Ramnath, the head of its operator channel in India, says the last year was an aberration caused by the entry of newer mobile operators which gave consumers a significant tariff arbitrage. “Though that hasn’t happened in other countries, the Chinese rebranded and unbranded phones benefited from it,” he says.

Ramnath also blames arbitrary valued added tax (VAT) hikes ranging from 1 to 8.5 percent across different states, causing many of its consumers to turn to the grey market. He does admit, though, that Nokia’s competitors also benefitted from the dual-SIM trend, something it took time in responding to.

“But the market is moving away from handset features to handset plus services. It is ‘What else can I do beyond voice and SMS that can impact my life?’” he says.

In his opinion, email or banking on mobile phones will be examples of this shift, which Nokia will address through its services like Ovi and Mobile Money. “The number of mobile email users will increase from 7-8 million currently to about 130-140 million by 2013-14,” he says.

Thinning of the Herd

Globally, it is unusual that the mobile phone market is crowded with so many manufacturers as it is in India.

“There are 143 mobile phone companies in India. The three multinationals – Nokia, Samsung and LG – have their own local manufacturing, while the remaining – 37 foreign companies and 103 domestic ones – are all merely importing and selling phones in India. Of course, all of them will not survive,” says Agarwal.

"Though in the short term the market may keep growing in leaps and bounds, there may not be as many players in the future. You will need to evolve,” says Naveen Mishra, analyst with IDC India.

They are right. Only a handful are likely to make it through the inevitable melee that will play out over the next couple of years amongst these 140. Four characteristics are likely to define the survivors, scale being the first.

Infographics: Hemal Seth

“The benefits of scale are many – the best distribution partners, stable margins, supply chain purchasing power with manufacturing partners, branding and ad dollars that stretch across a larger base and the ability to sustain the logistical cost of a national footprint,” says Wadhera.

Reaching that scale – more than a million phones every month at the minimum – will require customers to ask for specific brands at mobile stores instead of being merely sold whatever brand earns the retailer the most margin — a combination of pull and push, as the industry terms it.

Building strong brands usually takes plenty of time and money. But since time cannot be bought, companies are doing the next best thing – pouring money into advertising. Stars will be signed on for endorsements, cricket tournaments will be sponsored, primetime ads will be run and crores will be burnt. Agarwal says he has spent Rs. 50 crore this year on advertising this year alone, and he’s got a long way to go.

Ironically, the survivors will also end up becoming more like the incumbents they were trying to dethrone for so long – investing significant amounts of money to put up their own manufacturing plants and on R&D to create truly

differentiated products.

The push for local manufacturing is being mandated by the union communications ministry which wants to create a domestic manufacturing ecosystem to generate additional jobs and taxes while minimising the so-called security threat from phones made in China.

“The government has been threatening us with a 20 percent safeguard duty on imported phones if we don’t manufacture locally. In fact, there is even talk of a 31st December 2010 deadline,” says Agarwal. With his three plants already churning out mobile batteries and chargers, he is planning on adding a new one for making handsets too.

Vikas Jain, one of the co-founders of rival Micromax, says he too is evaluating local manufacturing, having hired KPMG to do a feasibility study. “Local manufacturing is an opportunity Micromax is exploring aggressively as it allows for both redundancy and nimbleness in the supply chain,” says Wadhera.

The most critical of the success factors is designing the next generation of phones that will continue to keep the cash registers ringing. After a while, sustaining the breakneck pace of innovation the industry is used to, with entire product lines being replaced every six months, will become impossible. Maxx alone has introduced 45 models in less than two years of which 25 have been phased out, with another 27 in the pipeline.

“While the masses were okay with a phone with a flashlight 18 months ago, that’s not even playing stakes anymore,” says Wadhera. Which is why, he says, R&D will become Micromax’s primary engine of differentiation.

From being a “fly-buy” phone brand, Micromax today claims to have exclusive deals with Chinese original design manufacturers, or ODMs (nobody else would have access to their designs). It’s also working closely with chipset makers to tightly integrate their product features into its phones. Recently, it hired the head of R&D from a global company to steer its own efforts.

Agarwal, meanwhile, is introducing Google’s Android-powered smart phones in September starting at a price point of Rs. 8,000. He believes that half the Indian users will switch to such smart phones in the next couple of years, provided prices go down further.

“Today Micromax and Maxx are brands, but if they don’t entrench themselves through product differentiation then over time they will lose their edge and become me-too brands,” says venture capitalist Relan.

In short, today’s aggressive challengers will need to morph into tomorrow’s defensive incumbents.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)