Make This Call, Kapil Sibal

This is the right time for a change in India's telecom scene. It remains to be seen whether Telecom Minister Kapil Sibal will bite the bullet

Alaskan Crab fishing, logging, coal mining and ice trucking are some of the most dangerous jobs in the world. And then there is the job of being the telecom minister of India. Kapil Sibal is finding this out the hard way. He rode out of the fortress and into the battlefield of doublespeak swinging the wheel of logic and the statistics. He now stands beleaguered and besieged, accused of doublespeak himself. He would desperately want to make it back to the fortress without any further damage to his reputation. When he took over, he said that his 100-day plan would fix licensing, spectrum allocation, tariffs/pricing, flexibility within licenses, spectrum sharing, spectrum trading and merger and acquisitions. But don’t forget his constraints. There are multiple investigations into telecom’s murky past by various agencies like the CBI, CAG, possibly a JPC and finally the Supreme Court which has even asked for chargesheets to be shown to it before they are filed.

So what can Sibal do?

Pay Before You Grow

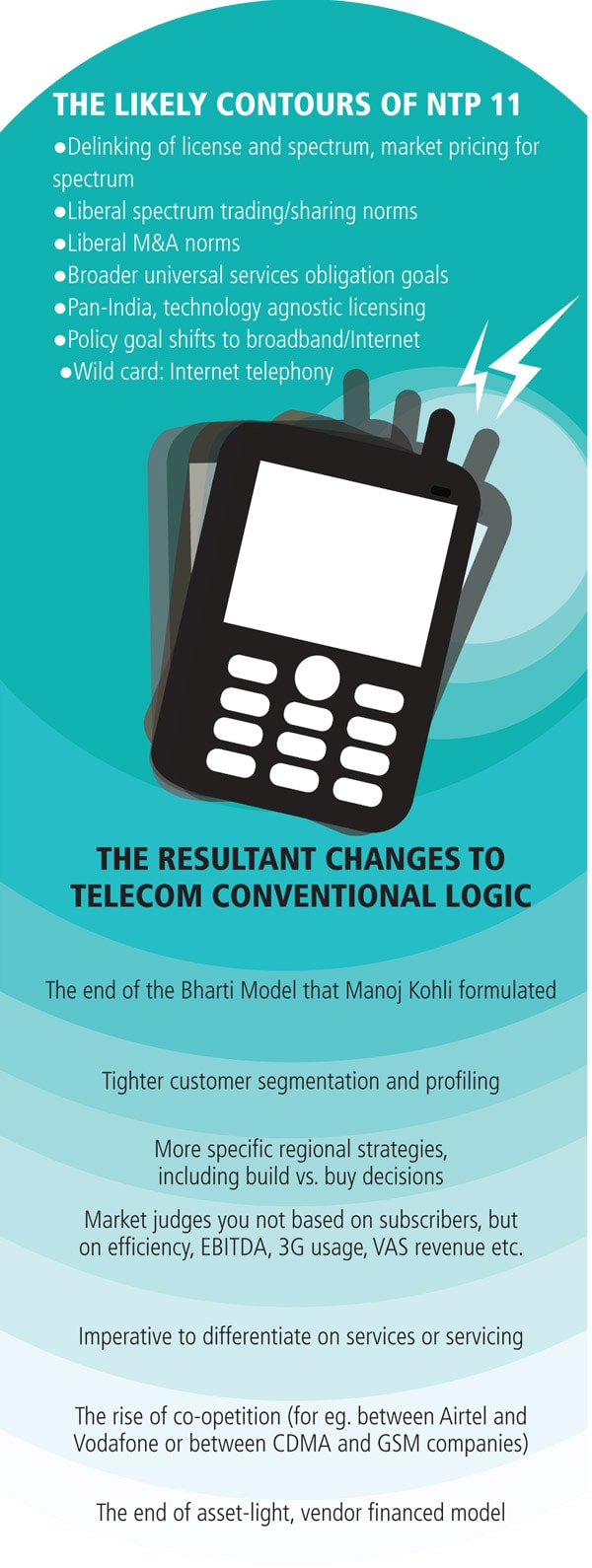

His big move will be to charge market prices for spectrum. Already, licenses have been de-linked from spectrum, and companies will need to pay fairly significant market-linked rates for spectrum. If we go by the recommendations of the February 2011 TRAI expert committee report on spectrum pricing, a single MHz of pan-India spectrum in the 1800 MHz band could cost anywhere between Rs.1,769 crore to Rs.4,571 crore, depending on whether it was part of the contracted minimum or over and above that.

The single biggest reason behind spectrum suddenly becoming so expensive was the 2010 3G auctions that netted the government nearly $15 billion. J.S. Deepak, then a joint secretary with the Department of Telecom, was the architect of that auction, much against the wishes of his minister, A. Raja, say insiders. “The 3G auctions were the only reform in the telecom sector for nearly five years, and one of far reaching proportions. We got a market-determined price for spectrum, we sold each and every piece of spectrum and the government got its fair share of revenue from it,” he says. Suddenly everyone’s eyes got opened to the immense monetary value of a resource that was being doled out for free.

Of course, operators are up in arms about shelling out billions of dollars for spectrum. Their argument-cum-threat against market prices for spectrum goes like this: Paying billions for spectrum will stretch our balance sheets inordinately, leaving us no choice but to hike consumer prices significantly.

Well, their fear is partly justified because the existing way of doing the telecom business is about to be destroyed. It was Bharti Airtel under Manoj Kohli that discovered the Holy Grail of Indian telecom first. Its three simple tenets were: Build your towers and expand your network, in a vastly underpenetrated market getting customers would never be a problem; give away SIMs for next to nothing and minutes at progressively lower prices, adding both subscribers and network usage in the process; get spectrum from the government for free by showing subscriber growth, all as per policy, mind you.

And as long as the market kept growing, telecom vendors too were willing to give their equipment on a rental basis. Sometimes they even financed the equipment on easy terms for operators. Leading Chinese vendors like Huawei are understood to have offered newer players their equipment almost free of charge for the first two years of usage, with payments kicking in from year three.

Over time, most of its larger competitors caught on to the game as well, thus making the model almost the conventional logic of telecom. What’s even worse, most operators started fudging their subscriber data in cahoots with DoT officials, even submitting false affidavits to back up their claims.

Baseless Fears?

Operators fear that the new regime will make them poorer. But almost all experts say that’s rubbish. Yes, the costs go up, but they go up for everybody. No longer will some people pay high fixed costs to get into business while some others escape that. “In any market with a certain level of competition, an increase in fixed costs will have no impact on consumer prices but only on cash flows. But the high spectrum prices could in effect become a barrier to entry for cash constrained firms, thereby reducing competition for the large players,” says Rohit Prasad, a co-author of the TRAI report on pricing spectrum as well as an economics professor at management institute Management Development Institute, Gurgaon.

“It is misinformation being spread by operators that large spectrum costs will lead to higher prices. For instance, the cost of 3G spectrum amortised over the 20 year period of a license at an average interest of 1 percent per year, assuming even 20 million 3G users, works out to just around Rs.150 per subscriber,” says telecom veteran B.K. Syngal who before his current avatar as a principal with consulting and lobbying firm Dua Consulting, has led both public sector firms like VSNL and private ones like Reliance Communications.

Prasad’s co-author on the TRAI report, Rajat Kathuria, a professor of economics with Delhi-based management institute Indian Management Institute also agrees. “As long as there is competition and number portability, prices won’t go up significantly due to one-time spectrum costs,” he says.

Willing To Mingle

But economic logic will not prevent operators from crying hoarse. So, as a conciliatory gesture for shaking down telecom operators on spectrum charges, Sibal is expected to introduce a meaningful mergers and acquisitions (M&A) regime, including the freedom for companies to share or trade spectrum. The latter might be allowed subject to two likely conditions: That the government has received the fair value for the spectrum being sold from the seller, and that it imposes a one-off transaction tax like in real estate registrations.

Infographic: Smaeer Pawar

“No market in the world can sustain 14 operators. In most markets numbers one and two make money, number three rarely, while all others play the valuation game hoping someone will buy them,” says Vsevolod Rozanov, the president and CEO of service provider MTS India. “There is really no way for us to make money on voice, much less expect margins of 30 percent,” he says.

The new operators are finding it tough and they will continue to find it tough. Swan Telecom (now called Etisalat DB), Datacom, Loop and SingTel will have to figure out a big enough acquisition target if they want to survive in India. There is quite simply no calculation, permutation or possibility that anyone of them can ever become a profitable telecom business on their own. “These players have made their money, they don’t care about customers. They have no future and they know it too,” says Syngal.

With Uninor the case is a bit muddled. While there is increasing pressure from parent Telenor’s shareholders to show some kind of light at the end of the tunnel which currently doesn’t seem to be there — it also seems unlikely that the company will simply walk away from nearly $2 billion

in investments.

But MTS, notwithstanding its small size and lone-ranger CDMA positioning, is the joker in the pack. “Both Telenor and Sistema [chief shareholder of MTS] will try their damndest to survive in India. But Sistema might even try to acquire a GSM operator to provide voice services, becoming like Reliance or Tata in the process,” says Syngal.

Reliance Communications has for a while been offering a significant chunk of equity for sale, unsuccessfully. The crown jewel for any acquirer will be Idea, arguably the next best Indian operator after Airtel. It isn’t clear if its parent, the Aditya Birla group, is keen to divest it at this stage. But if and when it is, expect a sticker price of anywhere around $10 billion, says a high ranking telecom executive who did not want to be quoted directly.

One set of potential acquirers — foreign telecom firms — are unlikely to turn bullish on Indian telecom very soon. “There is panic amongst the ones who have invested into the newer Indian companies. They’re now working hard to try and silo their own activities in India from the way the license was granted to their partner,” says Dilip Cherian, founder of lobbying and PR firm Perfect Relations.

Those that haven’t entered India yet are adopting a wait-and-watch on the country, opting to see how the next 18-24 months turn out in terms of regulations and competition.

But all these permutations and combinations are dependant on one piece of conventional logic: That only three to five operators can co-exist profitably in the Indian market. But due to the sheer size of the Indian market, plus that there are still another couple of hundred million subscribers to go (albeit marginal ones) before saturation, there are those who say seven to eight is a fair number for India.

Truly Technology Neutral

Another policy thrust is likely to be the way licenses are structured and given out. National Telecom Policy 2011 (NTP 2011) might do away with technology- or geography-specific licenses in favour of a pan-India one, with the service provider free to decide which areas it wants to operate in and using what technology.

If that happens, operators will be forced to evaluate each geography they want to offer services in using a hard-nosed build-versus-buy approach.

If a particular state isn’t key to an operator’s long-term strategy, it might make sense to simply piggyback atop a competitor’s network rather than set up one itself. In such a scenario co-opetition — partnering your competitors in some areas — is likely to be a more sensible strategy than the antagonistic go-it-alone competition of today.

The best example of this is likely to be an alliance between a CDMA player, like MTS for instance, and a GSM player where the latter’s spectrum is used primarily for voice and the former’s for data. Even Airtel and Vodafone might end up sharing their 3G spectrum across complementary geographies.

But all this will require a lot of drive and push from the minister and given the public mood this is also the best time to make these changes. Telecom is an investment-intensive sector and in the current environment almost no one is willing to commit monies.

There are some sceptics though.

“Far from being a clean slate, NTP 2011 is more likely to be a residual document left over from the Supreme Court and CBI investigations,” says a grizzled telecom hand who refused to be quoted. It is up to Sibal to prove his detractors wrong.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)