Inside the Koch Empire

They control one of the world’s great companies, which they’re using to reshape capitalism, and politics, in their image. Liberals (and competitors) may hope they go away, but Charles Koch and his brother David are just getting started

A man who, by Forbes’ careful measure, is one of the 50 most powerful people in the world, one of the 20 wealthiest—and one of the dozen most vilified—is perpetually in a position to reflect. But given it’s Charles Koch’s 77th birthday, the calendar demands it. Especially with the presidential election that Charles has called “the mother of all wars” less than a week away, and with Koch Industries, the firm he has built into the second-largest private company in America, considering several more big acquisitions, including an 18,000-employee automotive glassmaker, Guardian Industries.

Yet despite all these momentous events swirling around his wood-panelled Wichita office, decorated with seascapes and looking out on to the prairie to the north, the legacy he wishes to initially address comes via a piece of paper with a colour photograph of his first grandson. The baby’s name: Charles. “My proudest accomplishment,” he smiles.

Given that he and his brother have been called “pigs” (by MSNBC host Chris Matthews) and protesters have unfurled “Koch Kills” banners at rallies, Charles clearly wants to use this rare interview to humanise himself, attaching some personal substance to his courtly Midwest manner. Yet, this grandfatherly presence is at odds with the business and political juggernaut that he and younger brother David have built in a systematic process befitting their MIT training.

Charles’ many critics on the left—including the US President—accuse him of accumulating too much power and using it to promote his own economic interests through a network of secretive organisations they call the “Kochtopus”. Ironically, the Koch brothers believe they’re fighting against power, at least in the political realm. For the Kochs, the real power is Central government, which can tax industries into oblivion, force citizens to buy health insurance and bring corporations like Koch Industries to heel.

“Most power is power to coerce somebody,” says Charles. “We don’t have the power to coerce anybody.”

The November elections—which David, in an interview after the results were finalised, termed “bitterly disappointing”—seem to confirm Charles’ last point. Not even the Koch brothers, who spent millions of dollars during this election cycle (they won’t disclose the exact amount) funding direct political contributions and issue-driven ‘nonprofits’, could coerce voters to back their candidates. Mitt Romney’s loss was a huge blow to them, both in terms of likely policy outcomes and personal reputation.

But those who think the brothers will now fade away don’t understand the Kochs. Obama’s victory was just a blip on a master plan measured in decades, not election cycles. “We raised a lot of money and mobilised an awful lot of people, and we lost, plain and simple,” says David. “We’re going to study what worked, what didn’t, and improve our efforts. We’re not going to roll over and play dead.”

The goal has always been, Charles says, “true democracy”, where people “can run their own lives and choose what they want to buy, choose how to spend their money”. (“Now you elect somebody every two to four years and they tell you how to run your life,” he says.) Both Kochs innately understand that—unlike the populist appeal of their fellow Midwestern billionaire Warren Buffett and his tax-the-rich advocacy—their message of pure, raw capitalism is a much tougher sell, even among capitalists.

So their revolution has been an evolution, with roots going back half a century to Koch’s first contributions to libertarian causes and Republican candidates. In the mid-1970s, their business of changing minds got more formal when Charles co-founded what became the Cato Institute, the first major libertarian think tank. Based in Washington, it has 120 employees devoted to promoting property rights, educational choice and economic freedom. In 1978, the brothers helped found—and still fund—George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, the go-to academy for deregulation; they have funded the Federalist Society, which shapes conservative judicial thinking; the pro-market Heritage Foundation; a California-based centre sceptical of human-driven climate change; and many other institutions.

All of these organisations, unknown to 99 percent of the population, and their common source of support, unknown to most of the rest, have provided the grist for conservative thinking since Reagan. It’s a measure of Koch’s success that 40 years after Richard Nixon was stumping for national health insurance, Paul Ryan’s Ayn Rand-tinged economics are just a little right of centre. That the Supreme Court’s conservative majority led by Chief Justice John Roberts has issued a number of pro-property rights, anti-government decisions in recent years. That when George W Bush sought a watchdog on regulation costs, he appointed a top Mercatus executive. And none of this was accidental—it took millions of dollars over decades. You can see the same process at work in David’s quest to find a cure for cancer. A prostate cancer survivor like the rest of his brothers, he has given $215 million to fight the disease so far, including $100 million to fund his own research centre at MIT.

But to really understand the Koch brothers’ long game—and how the political goals they espouse play out in real life—it’s essential to examine the ultimate source of their power: Koch Industries.

Their conglomerate boasts 60,000 employees, 4,000 miles of pipeline and enough refinery capacity to supply 5 percent of US daily fuel demand. It makes Lycra and Stainmaster carpet, Brawny paper towels and AngelSoft toilet paper. If Koch Industries were publicly traded—Charles said that will happen “only over my dead body”—it would rank among the top 40 US corporations in terms of market cap, on par with McDonald’s.

Charles and David own 84 percent of it, after a bitter split with brothers William and Frederick in the 1980s. Forbes estimates Charles and David each to be worth $31 billion, tying them for fourth place on The Forbes 400, behind Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and Larry Ellison, and they say they reinvest 90 percent of the company’s profits each year. In 2012, with revenues of $115 billion—and estimated pretax profit margins of 10 percent—that’s a stunning amount of money. How they then deploy all that cash, and delegate that control, is one of the world’s all-time capitalist case studies.

Koch Industries is generally thought of as an energy company, but that’s a misnomer: Their core competence is converting raw materials into valuable products. That’s what drew them, in 2005, to purchase Georgia-Pacific, then “a low-cost converter of cheap Southern pine”, as one Koch executive puts it, into lumber and household paper goods. As Charles sits in his office and explains the rationale for the deal—the company’s largest acquisition ever and its primary management challenge for the past seven years—it epitomises what makes the Kochs so successful.

First, it displays the muscle that comes from having a private company that has no net debt and that spews cash. Charles spent $6 billion upfront to buy Georgia-Pacific, and rather than satisfy quarterly earnings estimates or dividend-hungry investors, he directed the new division’s cash flow towards paying down the $15 billion in liabilities that it inherited. “Like we should pay dividends and borrow big money?” Charles asks, before answering his own rhetorical question: “That puts the company at risk.”

More critically, it reveals the business roots of their worldview. Koch Industries applies the ideas of Friedrich Hayek to making money. Hayek, dean of the so-called Austrian school of economists, celebrated the chaos of decentralised decision-making as a way for individuals to decide what’s in his or her best self-interest. So while ownership is concentrated in the hands of two men, Charles—who has had management control since his father designated him as chief executive in 1967—tries to train each of the company’s employees to act as if they own the portion of the business they oversee. The Kochs have trademarked their take on Hayek: Market Based Management. Koch Industries has no centralised pay scale. It doesn’t peg bonuses to firm-wide profitability, and even the salaries of machine operators are often calculated in part on how efficiently they run the processes they oversee. Middle managers can earn far more than their base salary in bonuses, which are determined partly by the long-term return on the capital they invest. Market Based Management dictates they can earn more by turning around a faltering business than playing it safe in a consistently profitable one. “We try to evaluate how much value an employee is creating here and reward them accordingly,” says Charles, in an inversion of Marx’s famous equation.

Charles styles himself as a professor who manages more by the Socratic method than by decree, probing managers with questions designed to steer them towards long-term interests. Employees, unsurprisingly, like controlling their own destiny, even in heavily industrial, unionised businesses. Thirty percent of Koch’s 50,000 US employees are in unions, yet the company’s last significant strike was in 1993.

As Koch Industries struggled to digest Georgia-Pacific, Market Based Management forced numerous long-term decisions. Executives first defined what they needed to accomplish: To improve Georgia-Pacific’s low-end products like Brawny paper towel, which were being squeezed between private-label goods and premium brands. Once they determined that course of action, they followed it no matter where it led, even when it meant investing $1 billion in new papermaking machinery and increasing the efficiency of its pulp mills. Employees were given financial incentives to do their jobs more efficiently, including learning the intricacies of their machines to cut down on breakdowns and unnecessary maintenance expense. One result: Georgia-Pacific’s Green Bay, Wisconsin, paper plant is producing the same amount of paper towel and toilet paper as before with half the workforce and sharply higher profits.

Koch executives also had to devise a marketing plan to compete with Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark, each with generations of consumer marketing experience. That’s still a work in progress—Koch had little experience selling brand-name products in retail stores.

The timing for all this investment couldn’t have been lousier. Just as the company began to revamp its paper towel and toilet paper businesses, the financial crisis and housing market collapse devastated Georgia-Pacific’s building-products division. No matter. The Koch long-game strategy is absolute: If it makes sense to them, the Kochs stay with the plan, no matter how burdensome or how long it takes. “We buy something not to milk it but to build it, to take its capabilities and add to them, and build new businesses,” Koch says.

Five years into the deal, that strategy was easy to fault. Seven years in, it’s looking smart: The $21 billion purchase, factoring in the debt, is now worth 30 percent more, Forbes estimates.

Hayek isn’t the only political philosopher to dramatically shape the Kochs. The brothers’ hatred of centralised controls stems as much from Stalin, a feeling inherited from father Frederick, the son of a Dutch immigrant who settled in tiny Quanah, Texas, in 1891. Fred Koch studied chemical engineering at MIT and worked for the Soviet Union after big oil companies drove his US refinery-engineering firm to the brink of bankruptcy with patent litigation. In the USSR, the elder Koch made a fortune building refineries for Stalin—but developed a disgust for communism, and for his benefactor, after his Russian associates were executed in purges.

Fred returned to the US on the eve of World War II and built an even larger fortune around Rock Island Refining, a refinery and oil-gathering pipeline system in southern Oklahoma, and a part-interest in a refinery outside of Minneapolis.

Fred’s four sons—Charles, David, Bill (David’s twin) and Fred—grew up on his family’s land outside Wichita. Charles recalls his father working him from dawn to dusk, while his friends played golf and tennis at the nearby country club. “He had me work, because if I didn’t, I’d get in some sort of trouble,” Charles now says.

Charles followed his father to MIT, as did David and Bill, earning master’s degrees in chemical and nuclear engineering and going to work for the consulting firm of Arthur D Little. But his father, suffering from advanced heart disease, kept pestering him to return to Wichita and run the business. At that point, the refining business was earning $1.8 million a year on sales of $68 million (much of it low-margin oil pipeline revenue) and the engineering business was breaking even on $2 million a year.

Fred gave his son the refinery-engineering business to run with a simple command: “You can run it any way you want, but you can’t sell it.” Charles quickly realised short-term thinking was holding the business back. His father was obsessed with conserving cash to pay taxes, and managers were losing business because they refused to share design data about equipment.

He saw the business could grow much bigger and, in a pattern he has maintained to this day, steered the firm’s slender earnings into projects like a new factory in Europe. “I didn’t care about living high on the hog,” says Charles, who like Buffett lives in an unpretentious house, constructed on his family’s property in 1975. “I wanted to build something.”

Gradually, Fred Koch turned more of the business over to Charles, who overruled cautious managers by expanding Rock Island’s pipeline system into new states and buying truck lines to efficiently collect oil from new wells. Charles says he learned he could take profitable risk by investing in long-lived assets his customers didn’t want to buy themselves.

Koch’s father died in 1967 at age 67, shortly after handing full management control over to Charles, setting in motion the two most momentous turning points in the company’s history. The following year, Charles made the riskiest, and likely most profitable, move of his career. His family owned 35 percent of the Pine Bend refinery outside Minneapolis, with Union Oil of California (Unocal) holding 40 percent and J Howard Marshall owning 15 percent. Koch wanted to buy out Unocal, but the company was asking too much. So he persuaded the older and more experienced Marshall—who later became infamous at age 89 for marrying the young stripper-turned-Playboy-pinup Anna Nicole Smith—to combine his 15 percent interest with Koch’s 35 percent to prevent Unocal from assembling a majority stake to sell to outsiders.

The risk paid off handsomely. Marshall’s heirs hold Koch Industries stock worth at least $10 billion. And while Charles took on a potentially crippling $25 million in debt to buy out Unocal—something he has eschewed ever since—Pine Bend evolved into a cash engine. While there were mistakes, including a disastrous foray into oil tankers at the top of the market in the 1970s, the winners far outweighed the losers.

Koch Industries swallowed a fertilizer business, thousands of miles of pipelines, DuPont’s fibres business in 2004 and Georgia-Pacific the following year. Charles doesn’t profess any particular love for gritty industrial businesses. “That’s the hand we’re dealt,” he shrugs.

The second turning point was a byproduct of Koch’s success: The civil war that still defines the family. Feeling marginalised by Charles, David’s twin, Bill, and older brother Fred tried to wrest control of Koch Industries in 1980. David aligned with Charles and again persuaded Marshall to stick with them. Lawsuits flew, and Charles and David bought out their brothers and other shareholders for $1.3 billion in 1983. It seemed like an astronomical amount at the time, but Charles and David, in looking decades down the road, pulled off one of the great deals in business history.

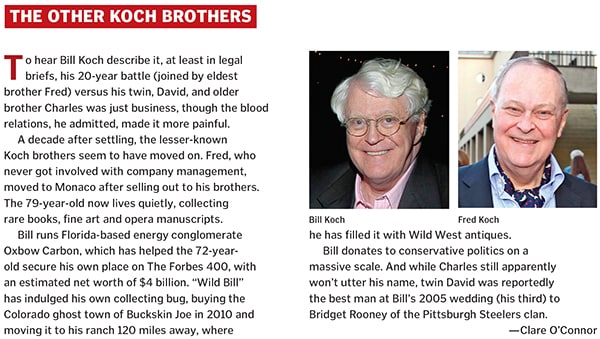

It also led to a decade of family litigation. The suits were eventually settled and Bill went on to build his own $4 billion energy company.

Charles’ remarkable business success sets him up for the criticism the brothers receive— criticism that goes way past simply making lots of money and spending it to shape the political landscape.

Given their strict adherence to the principals of transparent free markets, the Kochs’ secrecy seems hypocritical. While Charles has never been shy about enunciating his goals, his annual retreats for rich conservatives look like conspiratorial cabals.

While the ACLU joined Koch-affiliated groups like Cato in opposing limits to cash-fuelled political speech, as decided in the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United case, conservatives have touted both unlimited speech and unlimited disclosure. The Kochs’ large-scale efforts to hide their political activities by funnelling millions through Americans for Prosperity and other putative charitable organisations—something both sides of the spectrum do, and something acknowledged as a blatant end-run around disclosure requirements—don’t seem to jibe with their convictions.

Charles says he follows the law, and defends anonymous giving. “We get death threats, threats to blow up our facilities, kill our people, we get Anonymous and other groups trying to crash our IT systems,” he says. “So long as we’re in a society like that, where the President attacks us and we get threats from people in Congress, and this is pushed out and becomes part of the culture—that we are evil, so we need to be destroyed, or killed—then why force people to disclose?”

The second issue, given the Kochs’ vast financial interests: Whether their political activities are blatantly self-interested. Specifically, Koch Industries (a major carbon emitter) has contributed millions to organisations that have studied human-induced global warming with scepticism. While rejecting the claim that he is a ‘denier’—one group he funded has linked human activity to climate change—Charles warns about ‘confirmation bias’ in the assumption that rising temperatures are driven by mankind. “What makes good science is, it takes sceptics to challenge every theory,” Koch says.

While Charles, more diplomatic as the steward of the business, avoids throwing partisan bombshells, David, who lives in New York City and whose main activities surround philanthropy and politics, is less shy.And he has a message for anyone who thinks the Kochs won’t be a factor in 2016 and beyond: “We’re going to fight the battle as long as we breathe. We want to bequeath to our children a better and more prosperous America.” That means more of the same tactics, as well as whatever new ones election lawyers cook up.

But the Kochs are also capable of surprise, with their libertarian instincts often trumping their conservative ones. David, for instance, supports gay marriage and opposes the war on drugs. Their new political emphasis is fighting corporate welfare.

Unlike climate change, the Kochs come at this cause with a more pristine mandate, since many subsidies help their company.

For example, Charles counts the end of the ethanol subsidy as a major success, even though Koch Industries is a major ethanol producer. (This is not unusual in the energy business; Exxon Mobil routinely lobbies against subsidies because it doesn’t want to invest in any business dependent on unpredictable federal largesse.)

While Obama talks about getting rid of lobbyists, Charles says the “only way he can achieve that stated objective is to get government out of the business of giving goodies”. “That’s like flies to honey,” he adds. “The first thing we’ve got to get rid of is business welfare and entitlements.”

One thing to count on: Once the Kochs start down this road, they’re likely to stay at it. Ditto Charles Koch himself. He shows no signs or interest in slowing down. Buoyed by the Georgia-Pacific success, he’s again in acquisition mode.

Two things are for certain: Koch Industries will stay a private company—Charles says that he’s been estate planning for “many, many years”. And he has already planned for his departure.

While daughter Elizabeth isn’t involved in the business, son Chase, a Texas A&M graduate, is a senior vice president in the company’s agronomics services business (Charles declines to say whether Chase is being groomed for his job). Many of the executives above Chase are years from retirement, including Koch Industries President David Robertson and the heads of Georgia-Pacific and the Flint Hills refining business.

“We have the best leaders and the most depth of leadership we’ve ever had,” says Charles. “If I get hit by a truck, maybe it would get me out of the way and it would go better.” Spoken like someone who has had it all planned out, decades in advance.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)