India's E-Tail Battleground: Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal Fight for Top Slot

The ecommerce industry is currently a regulatory quagmire and customer loyalty is hard to come by. However, armed with deep pockets and tailored strategies, Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal are jockeying for the number one slot in the Indian ecommerce market

Alice Mathew, 46, recently bought a T-shirt for her younger son from Snapdeal because it was offering a “better deal”. “The price difference was almost Rs 100 for the same product on Flipkart.com,” says Mathew, an assistant professor at Mount Carmel College, Bangalore. Her rationale: “When I shop online, I look for the best deal and the best product. It doesn’t matter which site I’m shopping from.”

Her shopping philosophy is hardly unique: The Indian online customer is typically vendor-agnostic, and seeks the lowest price for the product of his/her choice. The online marketplace becomes a vast hunting ground for the best deals, with multinational behemoths and Indian ecommerce giants jostling to offer the best prices (at the cost of margins) to lure the fickle customer rupee.

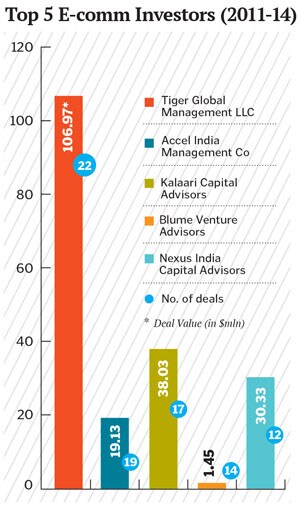

The intensity of competition has heightened over the past year. And the fight for the top slot in the $3.1 billion Indian ecommerce industry has evolved into a three-way tussle: Global biggie Amazon Inc, with a $143 billion market cap, entered India last year and is the most deep-pocketed. Bangalore-based Flipkart, with its recent funding of $210 million from Russian firm DST Global Solutions, has now received nearly $780 million in funds since it started operations in 2007. It recently paid $300-330 million to acquire rival Myntra (India’s largest fashion etailer) to strengthen its position in the fashion space. And the third, Snapdeal, which raised $100 million in May, mostly from investors such as Temasek Holdings, BlackRock Inc and PremjiInvest. It had earlier got $134 million from eBay Inc and others.

Flush with funds, they are now vying for customer mind space and wallet. But the lack of brand loyalty coupled with the absence of any major differentiators in terms of offerings and services is fast emerging as their biggest challenge. Promises like cash on delivery (CoD), assured delivery, no-questions-asked replacement policy, zero cancellation fee, free shipping and EMI options are no longer good enough for customers.

“That’s the reason ecommerce players either try to kill competition or merge with each other—to reduce consumers’ options so as to ultimately leave them with only one option and force them to be loyal,” says Harminder Sahni, founder and managing director, Wazir Advisors, a retail consulting firm.

In lieu of loyalty, the three competitors are focusing on strategy as their weapon of mass annexation.

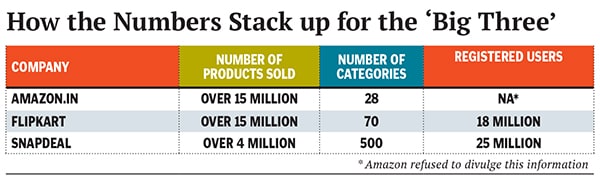

Amazon: Customer-Centric

It has been 20 years since Amazon started, but it is yet to turn profitable. That, however, has not stymied its aggressive and high-investment business model in every market, and India is no exception. Since it launched here in June 2013, Amazon has already built one of the biggest online product assortments in the country. As Indian laws prevent foreign ecommerce firms from starting a wholly-owned company selling directly to consumers, Amazon.in is operating as a marketplace for buyers and sellers: It offers over 15 million products across 28 categories.

Its global mission—to become “Earth’s most customer-centric company”—has dictated its local strategy. Take 790002. Means nothing to you, right? It is the pincode of a hamlet, Belamu, in Arunachal Pradesh. By tying up with the Indian Postal Service, Amazon has gained access to a vast network comprising 19,000 pincodes including far-flung locations such as this. Though Belamu makes for an unlikely harbinger of India’s ecommerce frenzy, it is an indicator of how Amazon is trying to catch the attention of the most unlikely customers.

“We believe that customer experience, selection and low prices are critical needs for consumers globally, and it is the same in India,” says Amit Agarwal, vice-president and country manager, Amazon India.

Amazon had started thinking about India back in 1998, when it bought Junglee Corp, a price comparison platform, for an estimated $200 million, and integrated Junglee’s core technology into its own services. The Junglee brand stayed dormant till February 2012 when, as a precursor to its entry into the country, Amazon launched Junglee.com, a price aggregator and selection website.

Last month, Junglee launched an option where customers can buy directly from the website, instead of redirecting traffic to third parties. “We have over 2,000 sites and most of them suffer from a trust deficit. Now, customers can buy directly on Junglee,” says Mahendra Nerurkar, general manager, Junglee.com.

Having established Junglee, Amazon is investing in the expansion of its own seller base. When it launched, it had less than a 100 sellers; today the figure stands at more than 5,000. To attract clients, it has introduced two ‘fulfillment centres’ which manage the entire purchase value chain, including warehousing, logistics, packaging and customer services, for sellers who opt for it. “The centres absorb the logistics and distribution burden so that sellers can focus on optimum selection and pricing,” says Agarwal.

Amazon India is investing heavily in logistics, says Mukund Mohan, director at Microsoft Ventures. This focus has allowed it to become the first ecommerce company to introduce guaranteed delivery in India. More than 2,30,000 items in about 20 cities are eligible for next-day guaranteed delivery. It also offers same-day delivery in select cities.

In the true spirit of online enterprise, its competitors have been quick to follow suit. Flipkart was the first with a promise of guaranteed same-day delivery across 10 cities. Not to be outdone, Snapdeal announced a two-hour delivery promise called ‘Snapdeal Plus’. To retain its edge, Amazon India has now launched a pilot project called ‘schedule delivery’ where customers can choose their preferred time slot for deliveries. The pilot in Mumbai is valid only for television set purchases. In Bangalore, customers can pick up deliveries as per their convenience from the nearest Bharat Petroleum or kiraana store.

“In the last six months, Amazon has upped its game. But they are doing too many things at the same time. The Indian consumer is not as evolved as those in the US, and they aren’t yet ready to appreciate these innovations or even pay for it,” cautions Sahni. “In any consumer-facing business, overdoing things can turn people away.”

Amazon’s other plans include tapping the sizeable mobile application market. The company anticipates a large segment of “mobile only and mobile first customers”. About 35 percent of its traffic comes from mobile devices, which is the fastest growth that the company has seen anywhere in the world.

Snapdeal: Target Non-Metros

“We are not an ecommerce firm; we enable ecommerce through our platform. We provide a platform for sellers to offer their products. We do not buy inventory,” says Kunal Bahl, CEO and co-founder of Snapdeal.

The model, he points out, has two advantages: Buyers get access to a wide range of products and there are no inventory costs for Snapdeal. This is also the reason why the investor community pegs Snapdeal as the most likely of the ‘Big Three’ to be the first to make profits.

“If you look around globally, large and profitable ecommerce businesses are marketplaces, be it Alibaba or Taobao [in China],” Bahl says. “Most companies are focusing on convenience, but we believe convenience itself doesn’t help. The biggest need is selection. That’s why a pure marketplace is better.”

And “wide selection” is what Snapdeal is betting big on. Its marketplace caters to over 5,000 cities and towns, offering more than 6,000 brands and has more than 40 lakh listed products across 500 categories. It has over 25 million members, about 30,000 sellers, and adds new products every 20 seconds. “Our view is that if a customer needs anything, we should have it,” adds Bahl.

Launched in February 2010, Snapdeal has quickly become India’s largest online marketplace. It claims to have the best prices for products on the back of its marketplace model. It has also started a two-hour assured shipping format and will deliver products within 120 minutes if customers are in the vicinity of one of its 40 fulfillment centres.

Snapdeal’s rise has been unprecedented in the ecommerce sector in India—it has been growing at around 500 percent annually compared to the industry average of 80 percent. The company is on track to reach its goal of earning $1 billion in revenue by 2014-2015, says Bahl.

Last year, eBay partnered with Snapdeal to strengthen its traction in India and invested nearly $50 million in it. The company intends to make 3-4 acquisitions this financial year. These acquisitions will mostly be in the space of mobile technology and data analytics, says Bahl. The company’s focus is on building technology that facilitates ecommerce through mobile devices. It expects 75 percent of its sales to be made from mobile applications. “For us, ecommerce is fast turning into mcommerce [mobile commerce],” says Rohit Bansal, co-founder and COO, Snapdeal.

The company is tapping customers in non-metros and tier-II and tier-III cities; 60 percent of its sales come from these areas, and Snapdeal is hoping to widen its reach. “Urban India has access to offline stores. Our focus is on places where they can’t get the product they desire,” says Kunal Bahl.

But as Snapdeal achieves greater scale, the challenges of managing logistics will catch up with it too. Mukul Singhal, vice president of SAIF Partners, a stage-agnostic investment firm, which has funded portals such as FirstCry, Zovi and Urban Ladder, points out that integrating vendors with technology is a crucial aspect of the marketplace model.

“Many a times, vendors are not ready for such integration because they don’t have the resources for it. A marketplace model like Snapdeal needs to ensure that technology integrations work seamlessly,” says Singhal, adding that a company’s technology platform should not become a hurdle for new vendors or for those who are not tech-savvy.

Any hitch here will make it difficult to keep track of products that are returned or payments that are not made. This could lead to a loss of money or product for the vendor. And rattling the vendor who, for the ecommerce player, is king. Sellers, beware!

Flipkart: Lead Categories

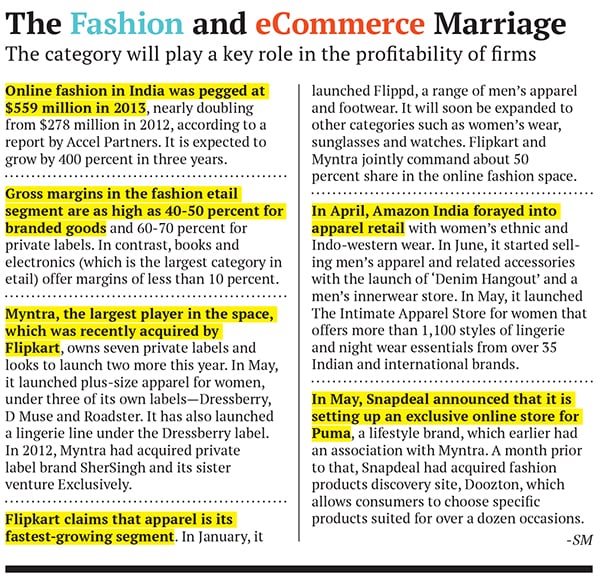

Late last year, Bangalore-based Flipkart set its eyes on online fashion retailing, a fast-growing segment. In May, it bought Myntra, the largest-ever acquisition in the Indian ecommerce space. Together, the two firms have over 50 percent share in online fashion retailing in India. In the long term, they aspire to occupy 60-70 percent of all online transactions in this space.

This acquisition cannot be considered in isolation. It, in fact, holds a torch to Flipkart’s future plans. “Fashion will be the largest category for Flipkart in the next few years and for ecommerce in general as well. We, at Flipkart, believe that we should be growing every category and we want to be the leader where we are present in,” Sachin Bansal, co-founder and CEO of Flipkart, tells Forbes India. He plans to invest over $100 million in the fashion category over the next 12-18 months.

Started in 2007 by two friends, Sachin and Binny Bansal, Flipkart is valued at nearly $2.5 billion. Its ecommerce platform offers over 15 million products across more than 70 categories. It has 3,000 sellers, 18 million registered users, and 3.5 million daily visits. It makes 5 million shipments per month.

“We are already leaders in the organised books market as well as the consumer electronics space. We intend to build further depth in these and enter new ones,” says Sachin. The company will scale up its supply chain and technology, and launch more customer-friendly features such as extended replacement guarantee period and priority customer service.

Despite urging, Flipkart is keen to keep its future plans under wraps. One of its early investors, Accel Partners, is also unwilling to answer specific questions on Flipkart. But Subrata Mitra, a partner at Accel, does indicate a broader perspective. “At Accel, we have made investments in home and furniture, jewellery and groceries. All these categories come with their own unique advantages and challenges, yet have the potential to become large players in India’s ecommerce story.”

There is a contrarian view, though, that Flipkart could be running the risk of spreading itself too thin by entering multiple categories. Singhal from SAIF Partners says the key to success for a horizontal firm like Flipkart lies as much in bringing new categories as in killing those product lines that are not working too well. “The key is to start with clear milestones and understand what to kill and when,” says Singhal. He gives the example of Flipkart continuing to sell apparels on its site despite acquiring Myntra. Last month, when the acquisition was announced, Flipkart promoters had said that both companies will remain independent.

Like other ecommerce companies, Flipkart is loss-making too. It reported a loss of Rs 281.7 crore for the financial year 2013, primarily because it upped its spending significantly to increase top line. In the previous year, it had recorded a loss of Rs 109.9 crore. But Sachin Bansal says profitability is not their immediate focus. Flipkart can stop investing in supply chain and technology and start becoming profitable immediately, he says. “But that would be a wrong strategy right now. We are in a dominant position, we should continue to invest, be the leader and grow the market,” he says.

It should be noted that it was in 2013 that Flipkart changed its model and launched a marketplace. This was after a probe by the Enforcement Directorate for alleged breach of the Foreign Exchange Management Act for possible violation of foreign investment rules. India, as of now, does not allow foreign investment in ecommerce firms selling products directly to consumers but permits it in the marketplace models. In its bid to adhere to Indian laws, Flipkart has created a rather complex structure. Its holding company Flipkart Private Limited is based in Singapore and owns Flipkart India Private Limited, which runs Flipkart.com.

The good news: According to multiple media reports, India is expected to bring down its FDI restrictions in ecommerce sometime this year. And this could be a game-changer for the industry.

The Real Winner

The battle for domination in the Indian etailing space is bound to be protracted. The outcome is fuzzy but here’s what’s clear: The spoils of war mostly benefit those for whom it is being fought—the consumers. “With so many players, it’s easy for me to get the best deals. Thanks to all the discounts and daily offers, sometimes I save as much as 50-60 percent on a purchase,” says Ivan Pereira, 30, marketing manager with a Bangalore-based apparel brand.

The entry of Amazon has brought an added sense of urgency and competitiveness in the industry, say experts. This is visible in the aggressive advertising in the space. “Spends on marketing and promotion have gone up significantly and communication to the customers is more intense,” says Pragya Singh, associate vice president, retail & consumer products at Technopak Advisors. “In future, pure-play etail will dominate in India, unlike in the US and UK where the penetration of organised retail is way higher,” she says. For her, Amazon’s competition isn’t its global rival eBay but home-grown retailers who understand the Indian landscape better.

With their sights clearly set on the long term, for Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal, there is only one objective—customer acquisition. While the cost of acquisition is spiralling skyward thanks to their capital-intensive investments across the board, for Anupam Gupta, a 40-year-old finance professional, the USP of each player is clear. “I go to Flipkart only for books and things like computer peripherals and mobile accessories. In India, Amazon’s site is same as that in the US. The service is smooth and cancelling orders is a breeze,” says Gupta, whose choice is not determined by discounts.

Mahesh Murthy, venture capitalist and co-founder, Seedfund, also believes that Amazon is here for the long haul. Amazon has already grown to about a third of Flipkart by spending one-tenth of what they did, he says. “They [Amazon] had problems in China due to various reasons… there are hardly any English speakers and the web rules are stricter. India is a far more aligned market for them, almost a subset of their US one,” adds Murthy.

There are, however, others who believe Flipkart stands a better chance here. This will be a more concentrated fight now, says Aashish Bhinde, executive director (Digital Media and Technology), Avendus Capital, an investment bank. “Flipkart has a strong lead as of now but it will need to continue innovating and wowing its customers to maintain that position.”

The broad point both investment bankers and investors agree on is that the Indian ecommerce market will accommodate multiple large firms but the endgame will belong to global companies with uninterrupted access to capital.

As Deepak Srinath, director, Allegro Capital Advisors, points out: “Of the three, Flipkart is the strongest brand right now. But in the long term, Amazon will lead over the others on the back of its expertise, technology and access to capital. Amazon does not need to raise capital from outside in the next 10 years.”

Vish Narain, country head, TPG Growth India, a private equity firm, says it’s important to assess how much more money is required by these firms to reach a scale of $10 billion or above. “Global ecommerce giants like Amazon and eBay are here, so unlike China where local companies have thrived, the success of these [home grown] firms is not guaranteed,” he says.

But the only guarantee that these firms are currently seeking is opportunity. With Nasscom estimating the Indian ecommerce industry will reach $100 billon by 2020, they have that assurance in hard numbers.

Game on, then!

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)