India: The Regret Economy

India's reputation takes a beating as the government plays ducks and drakes with policy

Rahul Dhir, the 45-year-old managing director and CEO of private oil producer Cairn India, is an exasperated man. In the six years that he has been running Cairn India, Dhir has battled bureaucratic red tape, unfriendly policies and systemic friction. But it still didn’t prepare him for Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee’s Budget speech on March 16. The company is bracing for a total hit of about $2.5 billion if the minister’s plan to raise the cess on crude oil to Rs 4,500 per tonne goes through. By the end of that day, Cairn India had lost nearly a billion dollars in market capitalisation.

On March 22, Dhir wrote a stinging letter to Petroleum Minister Jaipal Reddy and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh saying that the move could affect his company’s future investments in India. He reminded them that Cairn India had earlier withdrawn—in good faith—international arbitration against the government on the issue of royalty and cess payments in return for letting Vedanta Resources buy a majority stake in the company. “These [fiscal viability of contracts and viability of marginal fields with additional cess] combined are a disincentive to further foreign investment in the E&P [exploration and production] sector…,” the letter warned.

“We are on pause now,’’ Dhir told Forbes India about the $6 billion of planned investment in the Rajasthan fields to double oil production to about 3,00,000 barrels a day.

No policy announcement in recent times has upset foreign investors and created a perception of arbitrariness as Budget 2012-13. While the UPA-II government had become infamous for its inertia, nobody had expected it to reach into the past to fill its coffers. That is what the finance minister did with retrospective amendments to tax laws, making a recent Supreme Court verdict against the taxman’s demand of $2.2 billion on British telecom company Vodafone ineffective, and raising fears of diluting the authority of even the land’s final word of justice.

“India will lose significant ground as a destination for international investment if it fails to align itself with policy and practice around the world and restore confidence in the relevance of the judiciary,’’ a group of seven trade bodies, including Confederation of British Industry, Japan Foreign Trade Council Inc and United States Council for International Business, that together represent about 2.5 lakh companies, wrote to Manmohan Singh on March 29.

Justifying the amendments, the finance minister said, “India is not a no-tax country; it has a determined tax rate. Our country is not and cannot be a tax haven.’’ But that is not even anybody’s case.

“Nobody questions the right of the state to tax income, but the retrospective levy combined with a spate of other recent developments have created a groundswell of uncertainty,’’ says Percy Billimoria, senior partner at corporate law firm AZB and Partners. Billimoria says that there appears to be a sense of invincibility about the economy among policy makers but investors are not going to commit capital and move high tech manufacturing to India unless there is stability in tax and economic policies and simplicity in the regulatory framework.

“This sends chilling signals,’’ says Ron Somers of US-India Business Council. Somers says that industry is okay with paying up if the government wants to tax a transaction. But it should be prospective, not retrospective. He says India cannot afford to send conflicting signals when it is looking at $1 trillion investment in infrastructure. “You don’t change the rules in the middle of the game.’’

The finance minister’s move has further clouded the atmosphere of uncertainty and also put a question mark on the reliability of legal recourse.

“The amendments have diluted the authority of the Supreme Court,’’ says senior lawyer Harish Salve, who fought for Vodafone against the income tax department in Supreme Court. “I am telling my clients that the only way to do business in India is the Indian way.’’

What Salve is hinting at is negotiating the Indian bureaucracy and government with favours and lobbying rather than believing in the sanctity of contracts and rules, a method that many successful Indian companies are known to use effectively to mould government policies and procedures. In fact, that was the norm during the Licence Raj of the 70s and 80s. Big businessmen arguably spent most of their time cultivating politicians and bureaucrats, creating an oligarchic set-up with scant respect for rules and process.

That began to change in 1991, after Manmohan Singh, then finance minister, opened up the country to foreign capital and competition. Over the years, India gained in reputation as a country where democracy was deep-rooted and law was respected. Justice may be delayed, but not derailed. Promises enshrined in contracts and agreements would be met. The courts ensured that.

“An independent judiciary is not an ally of the government,’’ says Gopal Subramanium, senior lawyer and former Solicitor General of India. “Judgements of a court are not meant to go the government’s way.’’

There has been overwhelming condemnation of the finance minister’s move. “We are concerned about the proposed Budget measure,’’ British Finance Minister George Osborne said after meeting his Indian counterpart on April 2 in Delhi. “Not just because of its impact on one company, Vodafone, but because we think it might damage the overall climate for investment in India,’’ Osborne warned.

What Mukherjee refuses to acknowledge is that investors are not worried about paying tax. They are worried about not having a stable regime that upsets their plans mid-flight.

“The Indian dream is on ventilator,’’ says CB Bhattacharya, dean of international relations and E.ON Chair in Corporate Responsibility at ESMT European School of Management and Technology, Germany. “The government is doing little to allay foreign investors’ fears.’’ The fears are at multiple levels of policy, market place and labour market. Bhattacharya says investors in India could not be sure of meeting deadlines as there is no assurance of uninterrupted labour, goods and materials supplies. “They want returns within a certain period of time and there is no surety on that,’’ he says.

Short Term, Long Term

India desperately needs capital to build roads, ports, power plants and railways and create jobs and livelihood for millions entering the labour force. India is one of the youngest countries in the world with a youth bulge that could become a liability instead of opportunity if the right economic policies to attract capital are not in place, both in the short term as well as the long.

“India will remain a victim of international liquidity,’’ says a Singapore-based manager of a fund that has over $3 billion invested in the country. As nations compete for foreign capital, India could find itself in a difficult situation.

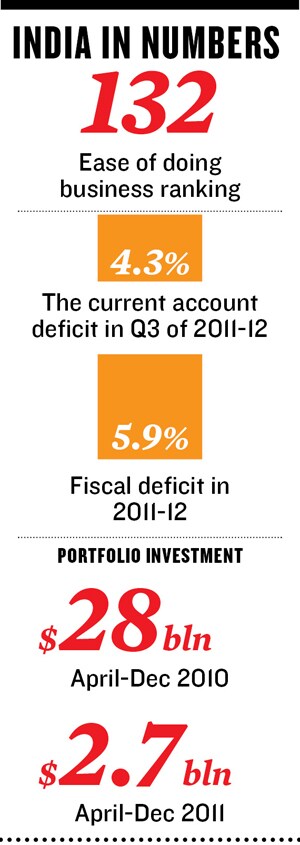

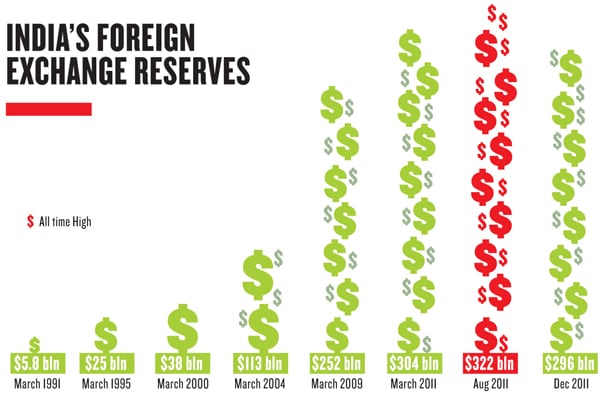

In the short term, foreign capital is essential because of the country’s trade imbalance. In the last three months of 2011, India’s current account deficit widened to 4.3 percent, nearly doubling from the previous year’s level. During the third quarter of 2011-12, India’s balance of payments experienced a significant stress as the current account deficit widened and capital inflows fell far short of financing requirements, resulting in significant drawdown of foreign exchange reserves, the RBI said in its review of balance of payments recently. The foreign exchange reserves were eroded by nearly $13 billion, or as much as was added to the reserves in the previous year by net capital flows. India ended 2011 with forex reserves at $296 billion, enough to cover eight months of imports.

Foreign direct investment is expected to come down because of policy uncertainty and increasing political risk while portfolio investments depend on international markets and sentiments which add to its fickle nature.

While India has almost always run a current account deficit, save for a brief period between 2001 and 2004, the country’s money managers had assumed that foreign flows could fund a deficit of up to 2 percent. If services exports, instrumental in keeping the current account deficit within bounds, suffer in the coming months and capital flows continue to decline, the balance of payments situation could become grave. Tightening foreign exchange liquidity could force the central bank to become even more conservative with forex spending. The 1991 balance of payments crisis is still vivid in the institutional memory of the nation. The man who confronted that reality is the prime minister today but a rather ineffective one. Even his word does not carry much weight.

Within days of his reassuring the Korean government of POSCO’s investment in Orissa, the National Green Tribunal ruled that the company will have to reapply for environmental clearance. Nothing came of Manmohan Singh’s assurances to German Chancellor Angela Merkel on a proposed railway coach factory at Madhepura in Bihar for which Siemens was keen to bid. In July 2011, the German Charge d’Affaires Christian-Matthias Schlaga wrote to the PMO seeking its intervention. The Germans wanted India to move ahead with the bidding process as Siemens risked funds tied up for the tender going unutilised. But the Railway Board did not even show the courtesy of replying to letters and reminders from the PMO on the project.

The Economic Times newspaper revealed recently that Manmohan Singh had ruled out retrospective taxation as early as 2010. In response to then British PM Gordon Brown’s concerns over the tax claim on Vodafone, Singh wrote on Feb 5, 2010, that retrospective taxation was not the norm in India and the company will have the full protection of law.

Despite the Prime Minister’s assurances, the taxman is becoming more powerful. Newspapers reported that the new Central Board of Direct Taxes chairman, Laxman Dass, wrote to 100 top income-tax officials in early February that revenue collection targets will have the highest weightage among performance parameters and their transfers and performance reports will depend upon meeting them. Since then, there have been reports of taxmen gunning for companies in a last minute scramble to raise revenues for the government. One of the weapons that were being freely used was attaching bank accounts and even draining the overdraft limits.

The Golden Goose

Despite the uncertainty over the ineffective political chain of command in the government as well as the Prime Minister’s constant refrain of coalition compulsions holding up economic reforms, India’s huge consumer market and growth potential makes it juicy bait for investors. RBI data shows net foreign direct investment into India stood at $4.5 billion in the third quarter of 2011 as compared to $1.2 billion the previous year.

Atsi Sheth, vice president and senior analyst at rating agency Moody’s in New York, says that much of the policy uncertainty is expected to be offset by the large size and growth projections of the market. But for foreign investors who are just now starting to consider Asia and India, and for whom the region is not yet critical to their growth, uncertainly is a significant deterrent.

“Many new investors would have come but for these regulatory uncertainties,” Sheth says. From a ratings perspective, he says for every step backward, there have been a few forward steps as well, partly due to a favourable business environment offered by competing state governments.

“I don’t think there is any surprise [in what the government did]. India was always high on political risk, taking one step forward and two steps backward,’’ says Dana Denis-Smith, managing director of London-based political risk company Marker Global. She says, however, that current trends are more worrying and people may think twice before entering into transactions and try to create offshore structures that reduce risk.

Creating complicated structures means less transparency and encouragement to shady capital. Difficult to operate economies typically tend to attract low-quality capital. India ranks 132nd in the World Bank rankings for ease of doing business.

The Heritage Foundation’s Economic Freedom Index for 2012 ranks India as the 123rd freest country for doing business—below the Asia-Pacific region and the world average.

ESMT’s Bhattacharya says it could result in India attracting those investors who have a high appetite for risk. “They may be willing to play with the system, play with human rights and cut corners. As a class of investors they may not be the best,’’ he says.

There are also those who have taken a knock yet remain confident about India. MTS, which lost its telecom operator licence when the Supreme Court cancelled 122 of them alleging procedural lapses, has threatened to drag the Indian government to international courts. Yet it remains keen to invest in India.

“I’d say that being a Russian company of global scale, India possesses a lot less risk than other developing countries as there are good government relations and a bilateral treaty,’’ says MTS CEO Vsevolod Rozanov. “The question is can you afford to be in India. Unilever and P&G cannot afford not to be in India but in sectors like telecom there are a lot of foreign companies like Telefonica of Spain that are not in India and are doing fine.’’

Richard Fanning, CEO of global risk advisory firm Control Risks, says that resource nationalism and imposition of taxes is not unique to India. Even France and UK have done it. “India will remain on the long-term radar of foreign companies, in spite of all this,’’ says Fanning. “But earlier people were moving in too fast. There was an India fever. Now there is a sanity check.’’

It is also possible that foreign investment will continue to flow to sectors that are far removed from government. Negativity among foreign investors would ensure that capital flows to companies that sell soaps, cars and home appliances rather than those that build highways, locomotives and power plants. It will lead to consumption driven growth unsupported by expansion in critical sectors, increasing transaction costs and inflation. As AZB and Partner’s’ Billimoria says, “Ultimately, international capital will go where it feels most welcome.’’

(Additional reporting by Cuckoo Paul, Sujata Srinivasan and Samar Srivastava)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)