How India's celebrated unicorns are losing the plot

The pitfalls of the growth-over-profitability mantra are fast catching up with India's startup ecosystem and its famed unicorns

Snapdeal founders Kunal Bahl and Rohit Bansal (left) admitted that they “painted themselves into a corner” after raising close to $2 billion thus far

Image: Amit Verma

Once upon a time, Subrata Mitra invested in a small Bengaluru startup called Mu Sigma. As the big-data analytics venture grew, it caught the attention of big-league investors like Sequoia Capital and General Atlantic, and they offered to buy Mitra’s small stake out.

That exit was around 2011 and “to date, that has probably been my best exit. Luck does show up at your doorstep once in a while”, Mitra recalled recently at a conference in Bengaluru. Mitra, an entrepreneur-turned-venture capital (VC)-investor, is himself very much in the big league now as a partner at VC firm Accel Partners’ Indian unit, which was created by recasting his firm Erasmic Venture Fund in 2008. Mitra started Erasmic with two partners—Prashanth Prakash and Mahendran Balachandran—in 2005 and merged it with Accel in 2008 to create Accel India. Not only was he a seed investor in Mu Sigma, but also the earliest investor in Flipkart, today India’s most valued startup.

Mu Sigma is that rare unicorn—a term for startups valued at $1 billion or higher—based in India. And, unlike Flipkart, its profits aren’t mythical. Further, despite its founder Dhiraj Rajaram’s messy and public divorce, the prospects for the company remain huge in the era of Artificial Intelligence.

Cut to March 2017 and Mitra says, “In today’s environment, what is an exit? I haven’t seen one in a long, long time, so forget about one giving it to the other, they’re largely non-existent in India.”

Through 2016, the signs of things to come were there, but even as smaller ventures folded or changed drastically—in food delivery ventures, for instance—hubris ruled. And, despite news of big cuts in the notional value of Flipkart, India’s startup scene seemed like it had become cool even for Silicon Valley engineers, and not just desis returning after a stint there. “It is where things are happening, this is just the beginning of a tech explosion,” Garrett Kinsman, a 21-year-old college-dropout-turned-software-programmer from California, had told Forbes India in November, on what drew him to work at Ola, India’s biggest ride-hailing service provider and the country’s third biggest unicorn.

And then the bad news caught up. In February, SoftBank Group, one of Ola’s biggest investors, said it had reduced by $350 million the value of two of its biggest investments in Indian startups—ANI Technologies, which operates the Ola network, and Jasper Infotech, which operates the online marketplace Snapdeal.

Ola is recently said to have taken anything between $300 million and $350 million from SoftBank and others, in a deal that valued the company at $3 billion to $3.5 billion. Compare that with the $5 billion-plus value that investors had placed on Ola only 18 months ago, when it had raised about $500 million.

There is no confirmation of the new fund raise either from Ola or SoftBank. However, if it is true, even the ‘down round’—which values a company lower than that of an earlier round—will be part of the more optimistic aspects of a reality check that India’s nascent startup scene is facing.

The situation is grimmer at Snapdeal where founders Kunal Bahl and Rohit Bansal admitted that they “painted themselves into a corner” after raising close to $2 billion thus far. They are letting go of a significant number of their employees to try to steer Snapdeal towards profitability over the next two years. They may need a miracle to pull that off. On March 17, CNBC-TV18 reported that GoJavas, a logistics company that counts Snapdeal as an investor, was facing complaints of non-payment of dues by a clutch of cargo delivery operators.

Image: Abhishek N. Chinnappa /Reuters

“What looked like a dream job then has turned out to be a working nightmare today,” a manager at Snapdeal, who had joined the company in more exuberant days, tells Forbes India. The manager has been directed to prune his own team as well. “The fat pay package is only on paper. The equity has not even been realised and is equivalent to tissue paper now.”

In a sobering reflection to employees on how the entrepreneurs allowed their venture to get out of hand, Bahl and Bansal wrote, “Let’s remember, GMV (gross merchandise value) is vanity, profit is sanity.”

The value of all the goods sold on their site was a source of boastful pride for India’s ecommerce businesses not so long ago with little regard to the discounts that made that GMV happen. For the year ended March 31, 2016, Snapdeal posted losses of Rs 3,316 crore on sales of Rs 1,457 crore, as a search on company financial information tracker tofler.in showed.

“With all the capital coming into this market, our entire industry, including ourselves, started making mistakes. We started growing our business much before the right economic model and market fit was figured out,” Bahl and Bansal wrote in the letter seen by Forbes India. “We also started diversifying and starting new projects while we still hadn’t perfected the first or made it profitable.”

What’s happening in India is like a “territory grab”, explains Ramprasad “Rahm” Shastry, who was an early investor in cab-hailing startup TaxiForSure, which was sold to rival Ola in March 2015. “I recall, about two-and-a-half years into TaxiForSure, our rivals started to offer discounts like crazy,” says Shastry, who is now the CEO of DriveU, a driver-on-demand startup that he co-founded in Bengaluru.

From ecommerce to ride-hailing, companies were trying to quickly get as many millions of customers as they could grab by offering discounts subsidised by money from the investors. In a shopping mall, one might come across a discount sale, where a merchant will still make some money because he has a large enough margin. In the ecommerce world, the discounts pushed the margins well into the negative territory, making the startups lose money on every transaction. “The whole idea was, at some point, we’ll raise the prices, the customers will be attached to us, they will buy more product, blah blah, blah, but the problem is, they needn’t. They could go somewhere else, and they do,” Shastry points out.

The market didn’t expand fast enough either, and barring a category or two, such as mobile phones, the scene remains nascent, with laughable penetration levels—about 0.2 percent to 0.3 percent for groceries, for instance—and customers didn’t change their behaviour fast enough either.

Shastry adds: “So they are in a downward spiral now, and they can’t do anything. They have already sold the customer the story that ‘it’s cheaper to go online’. Now things are coming to a head, because they can’t keep on discounting like crazy, they have to raise money from investors (again).”

Says Amit Somani, managing partner at Prime Venture Partners, which saw its portfolio company ZipDial being acquired by Twitter in January 2015, “Till the euphoria lasts, you’ll get funded. And when the funding ceases and the fundamentals aren’t fixed yet, now you’ve got this crazy burn rate.”

Somani declines to name specific companies, but says that some of the Indian startups saw daily burn rates of $1 million to $3 million. “That meant they needed $300 million to $1 billion a year just to stay afloat. It’s a Herculean, if not impossible, task.” (See Interview: ‘New Startups are Learning From the Mistakes of Others’.)

Even as they look for fresh funding, the Indian companies are in a winner-takes-it-all fight against some of the most well-capitalised companies in the world—Amazon, in ecommerce and increasingly in entertainment, and Uber in ride-hailing. Uber has a large war chest, Amazon is making money at the consolidated level, so they are willing to take the hit in India, a market that both see as vital to their long-term interests.

Investors who go “how much more money can I put, because I don’t see how I’m going to get it back” are even more careful today, Shastry says.

Recalls Somani: “I used to be at MakeMyTrip (as chief products officer), we went for an IPO in 2010 and raised $75 million. From the public market. In the US. On Nasdaq. That is what has changed.” Of late, a mere 18 months ago, some of India’s unicorns raised billions of dollars from VC firms on the back of what is now clear to everyone were unrealistic calculations.

And people know that because, “The crunch started in mid-2015 itself, first it hit the smaller guys, but it has now caught up with the unicorns as well,” a senior executive at a well-known venture capital and private equity company in Bengaluru tells Forbes India.

The time between 2011 and 2014 “was a crazy phase, where whoever had a plan got money. But it’s not like that anymore. Investors are really looking at scaleable, more realistic, models. At times they are even asking ‘when are you going to come through?’”

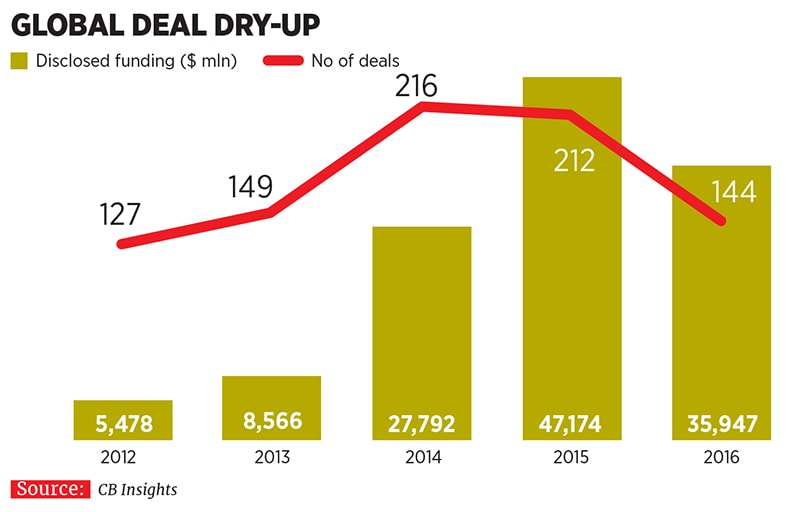

Globally, there were 25 companies that found unicorn status in 2016, research firm CB Insights said in a report in January, based on its survey of publicly disclosed funding of ventures. That was a 68 percent decline in “unicorn births” over 2015, the researcher said. CB Insights also tracks ‘down rounds’ and showed that of the 109 such transactions it had monitored in 2015 and 2016, 69 were in 2016 alone.

Funding deals to unicorns were lower in 2016 than any year since 2012, CB Insights said in January. There were 144 such deals in 2016 compared with more than 200 in 2015. And only 23 percent of the present set of unicorns joined the club in 2016, versus 42 percent getting there in 2015, the research firm added. Even where there have been ‘up rounds’, “it’s all valuation, but not exits”, the senior executive pointed out.

Online commerce in India is only at 2.5 percent of all retail in the country, research firm eMarketer estimated in August 2016. It is only expected to double to 5 percent by 2020, putting India well behind China, for instance, where ecommerce was estimated at 18.4 percent of all retail sales in 2016.

And while reducing cash transactions would likely help ecommerce in the long run, India’s demonetisation initiative couldn’t have come at a worse time for online retail as it hit cash-on-delivery, an essentially Indian element of the business. In December, eMarketer revised its estimates for the sector’s 2016 growth in India by 20 percentage points to 55 percent over 2015, from its earlier forecast of 75 percent.

Investors are increasingly circumspect about putting in more money and certainly not at higher valuations, as the path to an exit becomes a lot less clear. CB Insights data showed that while there were 18 unicorn exits in 2016 via mostly M&As and some IPOs, there wasn’t one in India. And of the eight or so unicorns in India, no company is charging ahead towards an IPO.

The drop in valuation is even more dramatic at Flipkart, India’s biggest ecommerce company, and widely seen as the country’s most celebrated startup. Some investors have slashed its value from about $16 billion only a year ago to about $5.5 billion currently. “Any way you look at it, Flipkart would be best served if it is less distracted by markdowns of paper valuations and more concerned about growth and the increasing competition,” Marcelo Ballvé, research director at CB Insights, told Forbes India in an email in December.

For context, ecommerce startup Jet.com, which was sold to Walmart in September 2016 for $3 billion in cash and $300 million in Walmart shares, had reportedly a $400 million annual revenue run-rate in November 2015. That meant the sale was closer to an 8x multiple, Ballvé pointed out. That pretty much aligns with Flipkart’s $16 billion value, at Rs 15,129 crore in revenue (about $2.2 billion) for the year ended March 31, 2016. It also, however, had losses of Rs 2,850 crore. (As this goes to print, Flipkart is said to have raised $1 billion, at a far lower valuation of $10 billion from investors, including eBay.)

Ola will break even in the next 2-3 years, its CEO and co-founder Bhavish Aggarwal told reporters in November, but declined to offer specifics. Since then, there have been at least two high-profile exits at the company, including CFO Rajiv Bansal and Raghuvesh Sarup, Ola’s chief marketing officer and head of categories.

However, Ola has also made fresh senior hires, notably former PepsiCo executive Vishal Kaul as chief operating officer, while elevating former COO Pranay Jivrajka to the position of founding partner—he was the company’s earliest employee.

The bottom line, however, is that the current business model requires Ola to subsidise a significant chunk of the cost of each ride with investor money, in order to keep rates low and attract users. Changing that will be a challenging task, partly because Uber has the money to wait Ola out and also because consumers in India aren’t going to stop buying cars to switch to ride-hailing. Nor are they likely to continue to use cabs as frequently if they’re made to pay the actual cost of the ride.

For the year ended March 31, 2015, ANI Technologies, which runs Ola, reported revenues of Rs 418 crore, but losses of Rs 755 crore, a search on Tofler showed. “In the US, a family may decide to opt out of a third or a fourth car and use Uber or Lyft, but in India, it is still an aspiration, a status symbol, with private car ownership at about 20 for every 1,000 or so,” Shastry points out. And in February, Ola cut its rates by a fifth as competition intensified for its home market Bengaluru.

In China, a far bigger market than India, Uber got out, ceding control to Didi Chuxing, also a company backed by SoftBank Group, which already had a dominant market share. In India, Ola’s lead over Uber is far more slender than the crushing lead that Didi Chuxing built up in China.

Everyone, however, agrees that India’s unicorns do need more money to raise their game. And “new investors will demand their pound of flesh”, says Mohandas Pai, chief advisor to Manipal Education and Medical Group, and co-founder of Aarin Capital in Bengaluru. “They will dramatically dilute existing investors and their rights, change the management, refocus the business strategy. There is also a possibility that they could push for the startups to be sold off or merged.”

Exits for investors depend on not just profitability, but on “hyper growth”, says the well-known Indian internet company executive. That is why becoming a successful “platform” is the Holy Grail of every tech startup. Few succeed. (Platform is industry jargon for a clutch of backend tech that combines to serve up a whole host of convenient, addictive services in one place via a smartphone app and a website on the customer-facing front.)

Amazon has that, from shopping to entertainment. And Paytm, India’s largest mobile wallet, and an eponymous online market place operated by startup One97 Communications, is attempting a rudimentary version. “Once you are a [successful] platform business, you can switch on profitability when you want,” the industry executive says. The catch is, history shows that this is incredibly difficult to achieve. Therefore, if the Indian unicorns can’t find the hyper growth, they will be left weaker against the genuine platforms.

Therefore many feel that the end game could be Amazon versus Alibaba Group, the Chinese ecommerce giant that is also the largest shareholder in Paytm. As far as Flipkart is concerned, the Bengaluru company isn’t to be discounted because it has been such a central force in India’s fledgling ecommerce market.

Even though co-founder Sachin Bansal’s awkward call for government protection, at a conference in Bengaluru in December, got wide publicity, his articulation of how Flipkart had the know-how to become the Isro of Indian ecommerce got less attention than it deserved, a few weeks earlier. He was referring to India’s frugal, but world-class space programme, while pitching the idea that Flipkart has earned a similar ability to frugally build something of high value for the country.

And in any permutation-combination of Amazon versus who—because no one is betting that Amazon will lose in India—Flipkart will likely remain the central part of the rival force, Ankur Bisen, senior vice president for retail and consumer products at Technopak, a consultancy, tells Forbes India. Flipkart may even retain its leadership.

“Alibaba once made an offer to invest significantly in Flipkart, but they didn’t like the valuation at which the offer was made,” a VC investor said on condition of anonymity. Alibaba has now invested in Paytm’s marketplace, which was spun out as a separate company—Paytm Ecommerce. That business is now gearing up to take on Amazon and Flipkart.

At Prime Ventures, Somani says he is still extremely optimistic about the long-term story in India. That said, “the things that were formed on this random euphoria, poor unit economics, poor cost of customer acquisition, poor gross margins, heavy dose of discounting are not sustainable. They never were.”

‘New Startups are Learning From the Mistakes of Others’

Amit Somani, managing partner at Prime Venture Partners, feels the sector still holds out long-term opportunities

On what changed over the last two years

When there is euphoria, and there is a kind of herd mentality, you are funding (a startup) on the premise of the future. What you can’t change is the unit economics, and the economics of the business. If the unit economics of the business, and/or the market structure is fundamentally unwieldy, then you are going to have a problem.

If you are running a business on negative gross margins, it’s like running two parallel lines, which never meet—even if you have a billion transactions. That was okay initially, because one was doing it on the premise of growing the market, land grab, market share and so on.

I used to be in the US between 1999 and 2002, when it was all about eyeballs. Whoever has the most eyeballs wins. But eyeballs don’t actually win. Eventually you have to have a real business with real revenues and real profits.

Therefore till the euphoria lasts, you’ll get funded.

On the way ahead

India, as a long-term market, is still great, but the things that were formed on this random euphoria are not sustainable. They never were.

The way out is to build a business and make money, stop giving discounts and freebies and so on. Businesses that are fundamentally not viable are going to shut down.

There is also a trend of new companies that have learnt from the mistakes of others. Two years ago, if you asked a startup founder “what is your CAC (customer acquisition cost), is it, say, one-third of LTV (life-time value)”, they would look at you as though they doubted that you were even a VC. It was like ‘just give the money, and I’ll do what I like with it’.

Now people are coming in and before we ask them, they are saying “let me show you my CAC, let me show you the cohort of users, the unit economics”. The presentation starts like that.

On investors and potential conflicts

Usually what happens is that the people who come later with the biggest cheques tend to have the strongest rights. Liquidation preference is a standard term, for instance. When a company sells, say in distress, typically the person who came last gets out first. There would, of course, be variations.

The root cause (of conflicts) is about the type of investors—problems will crop up if there are investors who aren’t in it for the long haul. That said, where it becomes hard is if a company isn’t really getting great business traction, funding outlook is difficult, notional down rounds or worse might have to be faced and so on, then it can deteriorate into a complete mess. This is when people might say ‘whatever we’re getting, let’s get it and get out’.

In such scenarios, it’s possible that the founder or the team may not get anything. The acquirer may say, “I don’t want to pay the angel investors or the VCs, I just want to pay the founders” and various other such options crop up.

For many angel investors, for a hot company, often VC firms will be willing to buy them out at a Series B for instance with a 10-20x return. At that time, the ‘fear-versus-greed’ phenomenon kicks in... “I don’t want to sell, this could be Google or Facebook.” You want 500x.

That’s where an investor has to be clear on the investment philosophy. There are those who are very clear that at a particular return they will get out. Most VCs play for the long haul, that’s their mandate, to stay invested for seven or more years so they can have massive returns for their winners. The best VCs play for the longest haul.

On the unicorns

To be fair, some of India’s top unicorns have positively changed people’s behaviour forever—five years ago, no one booked an Ola or ordered something on Flipkart. So the question now is, when the pricing is adjusted to what is sustainable, will we all stay, or will we look for cheaper alternatives?

(As told to Harichandan Arakali)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X