Dregs in NREGS

India's largest social safety net needs a quality upgrade. A village in Rajasthan may have the answers

The Roster

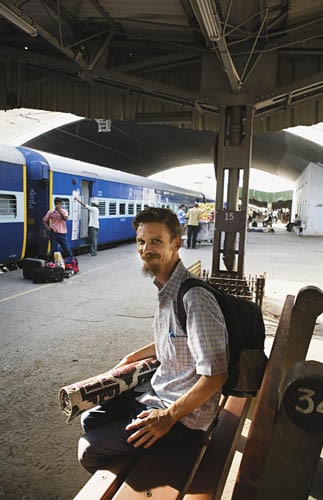

The Man Jean Dreze

The Mission

To improve the operation of National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS).

What’s the Big Deal?

India’s largest social safety net.

Why We Need It

To help the rural economy catch up with the cities, the main beneficiaries of economic growth in recent years.

The Challenge

Lack of proper field-level records and a mechanism for handling grievances. Need to create locally relevant infrastructure.

What Can He Do?

As a key influence in the original design of NREGS, Dreze can give ideas to plug loopholes.

People to Watch Kaluram Salvi, a village sarpanch in Rajasthan, who has solved some of the problems of NREGS

Budget Highlights

Allocation raised 144 percent to Rs. 39,100 crore.

Kaluram Salvi first came into the limelight in 2002, when he blew his fuse over 50 paise. The labour activist and budding politician was checking out a worker site at Phukiya Thad village in Vijaypura panchayat (council of villages) of Rajasthan. He saw that the officials at the site were paying the workers Rs. 59.50 for a day’s work, while the minimum compulsory wage was Rs. 60. Salvi argued with them till the additional money was paid. It was perhaps the turning point in his political career.

Today, with Salvi as the sarpanch (head), Vijaypura has emerged on the national map as a shining example of worker welfare. The grassroots innovations of Salvi and his team has led to a nearly flawless implementation of India’s largest social sector programme — the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS).

Salvi’s success has recently got corroborated — the government of Rajasthan now plans to take his ideas across all the NREGS sites in the state to plug leaks and make sure the benefits of the scheme reach the deserving. For a scheduled caste man in a multi-caste community, this is a rare achievement. “I only promised to do an honest job of implementing the different government schemes. I did not offer any favours,” Salvi says recalling his election campaign three years ago.

The good news about Salvi’s experiments couldn’t have come at a better time for the Congress-led government at the Centre, which is looking for templates of efficient but caring governance.

NREGS is an attempt launched in 2006 by the Manmohan Singh government to transform the rural economy through legally guaranteed employment for up to 100 days at a minimum wage of Rs. 100 per worker. The scheme, run jointly by the Centre and the states, has reached several milestones towards its goal, but suffers from the same deficiencies of most other official projects — corruption and diversion of funds.

An audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) found that crores spent on the scheme may not have reached the targetted beneficiaries.

NREGS is now ripe for version 2.0, without the leaks and the hassles of the first round. In this context, it is worth pondering how Vijaypura conquered the typical problems and made sure the scheme achieves its purpose.

One of the best judges of NREGS implementation is the development economist Jean Dreze, an Indian of Belgian origin. This luminary from the Delhi School of Economics was a key influence in the original design of NREGS. Dreze has lived and worked in India for 30 years, observing the nuances of the rural economy up close. He thinks experiences such as in Vijaypura present many answers to meet the next set of challenges for NREGS. There is also a clamour for urban employment guarantee and the use of modern technology to prevent corruption. “Many of these things will happen in due course, but it is important to realise that a lot of ground work still needs to be done to ensure proper implementation of the existing NREGS,” says Dreze.

That’s why the Centre can learn from Vijaypura. More than half of the total 1,600 households in this panchayat have participated in the programme. More than 60 percent completed the full quota of 100 workdays per household. What’s more, at many sites, women account for a lion’s share of the employment. “People work whole-heartedly because the scheme has given them a sense of dignity and partnership in development,” Salvi asserts.

So what did Salvi do right? Basically, he found simple solutions for complex problems.

Problem No Transparency

Salvi’s Solution He got the entire NREGS records of the village painted on a wall at the centre of the village. Along with complete worker details, it also displayed the 10 rights that adult members of each family have under the scheme. “At any point in time anyone can look at the records on the wall and verify their authenticity. Villagers can compare and complain if there is any divergence from their personal records. This move has given a lot of confidence to the people,” says Salvi.

Problem Embezzlement

Salvi’s Solution: Corrupt hands used to fudge muster rolls and pay for absentees. Salvi ensured that the attendance was always taken at the worksite in front of all the people and absentees properly marked with a zero against their names. “This way nobody can fudge the attendance records after the roll call because it would entail changing the serial order of the whole sheet,” explains Salvi.

Problem Poor record- keeping

Salvi’s Solution: Every worker now gets a Majdoor Maap Card. It is a daily log of the amount of work done by a worker. This card is signed by the “mate” (worksite supervisor) and stays with the worker as a proof of his efforts.

Problem Inefficient Workers

Salvi’s Solution: The mates are known to have allowed their favourite workers to play truant and still get all the money. The final outcome of a team’s task would fall as a result and everybody, including the hardworking ones, paid less than what they deserved.

Now, Salvi has made sure that workers are placed in groups of five and each group is given a specific task. In the end, all five members of a group are graded together and paid equally. However, each group is graded and paid separately.

“This system ensures that nobody wants to work with a poor performer,” explains Salvi.

Early next year, Salvi’s term as sarpanch comes to an end. And that’ll also be Vijaypura’s acid test: Whether it can continue its trail-blazing run as the creative outpost for the country’s biggest social security programme.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)