Don't Do It, You Dope

Indian sportspersons take drugs because they have gotten away with it so far. But now the authorities are playing catch up

It’s a small clinic in the heart of Mumbai and not very hard to find. There are no confusing bylanes to traverse. Ask anyone in the area where the sports doctor is and you’ll be pointed to his house that doubles up as his clinic. He says he graduated as a doctor from a Mumbai college in the 1990s. Today, he calls himself a fitness and health expert. His speciality: Giving ‘booster’ shots to athletes, bodybuilders, weightlifters, actors and models. “National level athletes come to me, some on their own, others are sent by their coaches. They want steroids and I inject them,” says the doctor who does not wish to be named. One cycle lasts between four and 13 weeks and costs start from Rs. 7,000 a cycle. It’s that easy to get a steroid shot in Mumbai. Stimulants, beta-blockers, anabolic steroids, diuretics, you name it and you can have it.

Doping is the worst kept secret in Indian sports. Badminton ace Saina Nehwal says she knows athletes that dope. Dr. P.S.M. Chandran, former director of medicine at Sports Authority of India (SAI) says it’s been part of the system for close to two decades now. Dr. Najib Nandi, a former medical officer at SAI, was forced to go on leave without pay in 2009 after he filed an RTI (Right to Information) to expose organised doping in SAI.

If Asian Games and Commonwealth Games gold medallists Ashwini Akkunji, Mandeep Kaur and Sini Jose hadn’t been caught, doping would have made news for a couple of days and then died down. The athletes claimed innocence and blamed it on contaminated food supplements that athletics coach Yuri Orgodnik gave them.

Chandran rubbishes their claims, “Any top class athlete who’s been caught doping and says he or she doesn’t know is lying. And if the authorities say they don’t know about it, they are lying as well.”

But the case of Akkunji and co. may not be that simple. Adille Sumariwalla, working president of the Athletics Federation of India (AFI) is positive that they are innocent. He blames the adulterated medical trade. “I don’t believe the girls have taken anything. It is the stuff in the market that is contaminated. These girls are under the WADA [World Anti Doping Agency] whereabouts clause [WADA requires athletes to keep them updated about their whereabouts at all times]. It doesn’t make any sense for them to do something like this.”

Indian athletes have no choice but to take supplements. The health pack provided by SAI is a joke. Funds and supplements provided by SAI often run out and athletes have to buy their own supplements.

If any of the supplements have steroids in them, it’s difficult for an athlete to know since they may be under a different name considering WADA’s list of banned substances runs into hundreds. Though WADA and NADA (National Anti Doping Agency) publish the list on their Web sites, not many athletes have access to the Internet.

The only way to lay this case to rest is to test the supplements from the same batch as well as the same supplier they were purchased from. The B samples of Kaur, Jose, Jauna Murmu and Tiana Mary Thomas tested positive on July 8. If the girls lose their appeal, they’ll receive a two-year ban considering it is their first offence.

“Such cases used to be common 10 to 15 years ago in the US. Not anymore,” says Dr. Don Catlin, founder of Los Angeles-based NGO Anti-Doping Research and Professor Emeritus of molecular and medical pharmacology at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. “Usually these supplements are manufactured in China,” he says.

Obsolete Methods

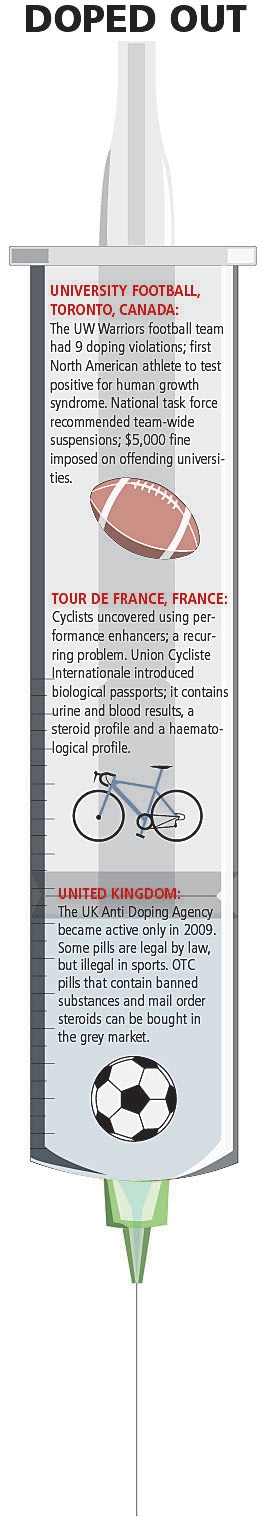

Doping is not a new trend. Athletes have been using various forms of dope for centuries. From opium and alcohol to blood doping and gene doping, athletes have always tried to get an edge over their rivals. Canadian Ben Johnson and Americans Marion Jones and Tim Montgomery are some of the famous names who have been stripped of their titles after they tested positive.

But athletes and coaches in the West and China are constantly on the lookout for better ways to game the system, say Indian players and coaches. Arjuna awardee Ashwini Nachappa says, “There are dedicated research labs for masking agents in these countries.” Masking agents are chemicals that hide the presence of banned substances in the body. “It is quite difficult to detect masking agents as new ones keep coming into the market and obviously we are not told about them. The most common drug that athletes use is different forms of testosterone and there are a lot of ways to camouflage it,” says Catlin.

While India may not be up to date on masking methods, it is still possible to beat the authorities if you understand the science behind doping. Fitness expert and trainer Firdaus Anklesaria explains, with a caveat that he never advises his clients to dope, the method behind the madness:

Most strength athletes take some form of anabolic steroids to increase their performance during the off season. It’s the way they cycle it that makes sure they don’t get caught. You know there are three drugs that have half lives (the time in which drugs can be detected in your system) of three, seven and 10 days and others that have half lives of six months. So, if you have 11 months to go before your competition, you first use those drugs that have a long half life. Then you use those with a shorter half life. You get clean a couple of months before the tournament. Some amount of strength will drop, but if you have been training properly and the dosages are proper you will still have more endurance and strength than a normal athlete.

A small miscalculation in the time-frame could mean that the drug stays in your system longer and increases your chance of getting caught. Of course, if WADA asks you for your sample during the off season you will be caught and the carefully structured programme is of no use.

“Smart athletes take short-acting drugs. You have strong drugs where a single dose can stay for as long as two weeks in your body and others that go off in a day or two,” says Catlin.

Sports people in India have gotten away with doping until now because India didn’t have an accredited WADA lab to test its athletes.

Sending samples to other countries was be expensive. That’s why most Indian athletes got caught only at international events. All that changed in January 2009 when NADA’s National Dope Testing Laboratory in New Delhi got WADA accreditation. Over 6,600 players have been tested since then and around 242 have been found guilty.

“That’s a very low number for a country like India,” says Catlin. “They should be testing at least 10,000 if not 20,000 athletes a year,” says Catlin who is also the founder of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory, the first anti-doping lab in the US.

Sumariwalla concedes that doping is a huge problem in India, but not at the national level. “It’s huge in the juniors [level]. A lot of coaches at schools and colleges encourage their students to dope to win medals,” says Sumariwalla. That doesn’t explain why so many national level players are

getting caught.

The world over, only 10 to 15 percent athletes are tested for doping. The chances of getting caught are minimal. “Everyone wants to enhance their performance,” says Chandran. “They hope that they don’t get caught.”

The next couple of years will be a tough time for Indian athletes who dope, as WADA and NADA will probably not get their feet off the pedal. This could herald a new era for Indian sport as the ‘system’ gets cleaned. Don’t expect SAI or AFI to help though.

When asked if the AFI can start testing athletes at the school and college level to ensure that the problem is identified early, Sumariwalla says, “It’s just not possible. We don’t have the funds. A national event at that level involves more than 3,000 participants. We can’t test all of them.”

What about the winners then? “If there are 70 events, then there are three winners in each. That’s 210. If there are three national events, we have to test 630 students. It can’t happen.” What about making sure that athletes only buy supplements from authorised chemists outside the National Institute of Sports (NIS) and sports camps? “We can’t regulate from where these guys buy their supplements. We can’t test all the supplements in the shops.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)