Cleaning Up the Indian Patent Office

To seed innovation and attract more patent applications, India needs an efficient system. The new patents chief P.H. Kurian has started with the basics

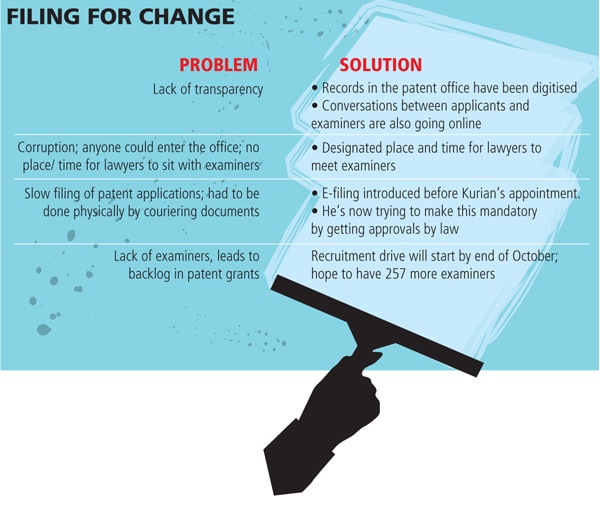

A few years ago, a visit to any of the four Patents and Trademarks offices in India would see all the clichés of the great Indian bureaucracy play out in spectacular fashion. The person who wished to file a patent had no idea if he was scheduled for a hearing. He would have to come and wait in a line day-after-day and hope that it would be his turn today. If his paperwork was not in order — and very often it wasn’t because there was no detailed matter available on how to file a patent — he would have to go back and waste a few more days getting his paperwork done.

A patent costs between Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 90,000 to file. If he finally did manage to get someone — because entry to the patent office was unrestricted, any lawyer could sit with examiners and try to make a quick buck off the applicant — to listen to him and evaluate his application, he would have to shell out anywhere from Rs. 10,000 to a few lakh as bribe depending on the seniority of the people evaluating his application or the potential of his idea/product. He couldn’t apply online because the process required him to write a bunch of letters or keep visiting the office in person.

It didn’t matter if a company had to file a patent. The company would have to operate in secrecy and make sure that no competitor got a whiff of the idea it wanted to patent. Senior officials in corporate legal teams say that companies have pushed their teams to try and block competitor’s patents or find out what they were filing, and see if that application could be replicated in their name.

It was no surprise that the number of patents filed until 2007-2008 was only 36,812 — companies used to file almost 80 percent of their patents abroad. India’s ambitions of becoming a global superpower were taking a severe beating on this front.

As factors like global warming and climate change began to gain importance, the government realised that most of the technology required to check climate change was very expensive, and patented. India may have missed out on several patents that would have probably not been as expensive as the ones developed abroad. Another factor that caused the government to wake up from its stupor was the growing trend of multinational companies shifting their R&D hubs to emerging economies.

GE, Microsoft, Philips, 3M are just a few examples of companies that are looking at innovation out of India very seriously. These companies need a good intellectual property (IP) office to work with to enable smooth filings of IP not just in India, but abroad as well.

In spite of R&D centres shifting their focus to emerging markets, the number of patents filed in India is relatively low compared to the patents companies file abroad. Himalaya, a herbal products company, has filed for 83 patents with just seven filed in India. Biocon has 993 patents to its name with just 118 filed in India.

More than two lakh patents have been filed in China. India couldn’t afford to sleep anymore. The government needed someone who could clean up the system. Fast.

Clean-Up Crew

Enter P.H. Kurian, an IAS officer with over 20 years of administrative experience under his belt. He is credited with bringing IT to Kerala in his last position as secretary and director, Industries (Investment Promotion). He has a master’s degree in chemistry but had no experience in IP before taking up the position of Controller General, Patents, Designs and Trademarks on January 22, 2009.

As expected, the senior babus in the IP office took offence to his posting. They were miffed that someone with zero experience had shot over them to the top post. Kurian, 51, knew he had a tough task on his hands. “For me, it was exciting to improve it administratively and create a credible system. That is a challenge in itself and it is possible, provided you get out of all these hurdles,” says Kurian. He rolled up his sleeves and got to work.

The first thing he did was to organise the filing process. People began to get a specific time and place where they could come to the office. There would be no more rushing into random rooms with lawyers and examiners. Initially, this was met with opposition but people have now accepted it.

The next step was digitisation. He made sure that all forms of documentation were uploaded online. After patent applications went online, people knew who was next in line to get their application examined. This brought down the level of jumps in the queue, which was another area where people could bribe their way through. Kurian says, “I have put in place an electronic system that pushes the overall system to move in a certain direction.”

Another hurdle he faces is that e-filing, while it does exist, is not mandatory. He has put in a request to change the law to allow for mandatory e-filing. He hopes this will streamline the process of filing for patent applications.

Viswanathan Seshan, country manager, IP&S-India, Philips Intellectual Property & Standards, says, “The Indian Patent Office [IPO] has become more transparent over the years, for example with the introduction of the e-filing facility for patent applications, the move to put all prosecution history online, etc. Due to these and other similar measures taken by the Controller General, our experience with the IPO has been constantly improving.”

Viswanathan Seshan, country manager, IP&S-India, Philips Intellectual Property & Standards, says, “The Indian Patent Office [IPO] has become more transparent over the years, for example with the introduction of the e-filing facility for patent applications, the move to put all prosecution history online, etc. Due to these and other similar measures taken by the Controller General, our experience with the IPO has been constantly improving.”

The basic clean-up done, Kurian then focussed on the biggest issue of all: Finding qualified examiners.

Let’s understand what happens once a patent application is filed. An examiner scrutinises the claim, conducts a search to test the patent on the merit of novelty, inventor, and usefulness. Once he examines the application, he gives his report of his findings to the Controller General, who decides if the patent should be granted or not. The examiner needs to be well-versed in the area in which the patent is filed in order to give a neutral report of his findings to the Controller General.

The Indian patents office is severely understaffed. There are 140 examiners who have a case load of 214 patent applications per head. An examiner at the European patents office, in comparison, has to handle only 90 applications at a time.

It is not a lack of talent, though, that is hindering the office from hiring people. Money is also not a factor. The base salary for a patent examiner is Rs. 40,000 per month, which is the highest starting salary for any officer in the government. But this is where bureaucracy rears its slow moving head again. “First, I need to see if eligible people can be promoted,” says Kurian. “Then, I need to see if people can be deputed from other departments, and I need to wait for one year to see this through. And finally, [only] after these two can I advertise for posts in the IP office,” he says.

It’s been over a year since he posted the vacancies. He hasn’t got the kind of people he wanted. He has advertised externally to hire 257 officials for this year.

Nevertheless, the results of his overall efforts are showing. Sukla Chandra, director, PACE at GE, says, “He has done something where patent agents and attorneys can discuss the patent face to face. He has allocated time for that and a special space in the office for that. He has tried to make the process post filing very easy.”

Apart from just hiring more examiners, Kurian stresses the need to have examiners who are specialised in an area of expertise. He says, “The scene when I came was that an engineer could see a pharmaceutical patent without basic knowledge of chemistry. I have done away with that. I have taken a few people from biotech, microbiology, and I have put it in one group; then electronic engineering is one group; mechanical engineering is one group, etc.” This is something he models after the Japanese patents office, the third largest office globally in terms of patent applications, and patent grants. In Japan, there are four main groups of examiners, and then there are sub-groups.

Kurian has tried to get the patent office to get its act together but this is just the beginning. Often, inventors don’t understand the need to file patents and this is something Kurian is trying to change.

He is aware that the IP office allows him to cater to just 5 percent of the population, but for that individual inventor, he is trying to create a system that will allow them the benefit of having thorough guidance as they come to the office on how to file for IP, and the importance of IP. “Technically, they have progressed. Their understanding of a search report is far better,” says Sushila Ao, who heads IPR at Biocon. “I would not say it is perfect. They still have a long way to go when I have to compare it with the US and European patent office, but it is a start,” she says.

(Additional reporting by Samar Srivastava; edited by Abhishek Raghunath)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)