A Year On, Didi Is Still Fighting In West Bengal

Mamata Banerjee came to power a year ago, ending a 34-year Communist rule, but she is rapidly losing urban support and is yet to find a way to improve the state's financial health

On the morning of May 7, nobody in West Bengal’s state secretariat had any doubt that the person who would arrive soon was the most important guest to step into Writers’ Building in the past one year. Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee herself had supervised arrangements to welcome the guest.

Banerjee personally selected the flowers. She ordered new silver cutlery, Makaibari Darjeeling tea and the choicest of cookies. When the guest, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton arrived, Banerjee was waiting outside her office to receive her. “We have never seen her wait outside her chamber to receive anyone. But she was standing there five minutes before Clinton was anywhere near Writers’ Building,” said an official in the chief minister’s office.

For the attention-seeking Mamata Banerjee, it was indeed a big deal. She was meeting one of the most powerful women in the world on home turf to talk about possibilities and priorities that would help Bengal, most importantly, attract private capital to build industries and create jobs.

“This is a matter of pride that a US Secretary of State has come and talked to us here for the first time after independence,” a visibly elated Banerjee told a news conference after the visit.

Banerjee herself had joined Clinton on Time magazine’s 2012 list of the world’s 100 most influential people for excelling in New Delhi’s back rooms, where political horse trading is the name of the game.

“On the streets, she out-Marxed the Marxists. And as chief minister of her home state, she has emerged as a populist woman of action—strident and divisive but poised to play an even greater role in the world’s largest democracy,” the magazine said.

Banerjee’s role in Indian democracy, especially when it comes to support for economic decisions, has certainly been divisive. Many have called it regressive. She has blocked a government move to allow foreigners to invest in multi-brand retail in India. Banerjee shockingly forced Dinesh Trivedi, the railway minister from her party Trinamool Congress, to quit when he sought to raise rail fares after a decade-long freeze. She also stalled an international water agreement with neighbouring Bangladesh, presumably because Delhi did not consult her properly. Finance Minister and United Progressive Alliance’s chief trouble-shooter Pranab Mukherjee now refuses to deal with her and prefers to speak with state Industry Minister Partha Chatterjee. In short, Banerjee is now considered the enfant terrible of the shaky alliance.

Her reputation for mercurial decisions is such that the foreign ministry was holding its breath during Clinton’s visit. “She [Banerjee] could have suddenly refused to meet, which could have become such an embarrassing situation for the entire country,” says a senior official of the ministry.

Within the state, former supporters have deserted her. The arrest of Jadavpur University professor Ambikesh Mahapatra for circulating a cartoon of Banerjee and jailing of scientist Partha Sarathi Roy allegedly for protesting an eviction drive has shocked Bengal’s intelligentsia. “This is not the Mamata I knew,” says dissident TMC member of parliament Kabir Suman. Revered Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi, who supported her during the Singur agitation against land acquisition, now calls her government “fascist”.

After meeting Banerjee, Clinton, however, had high praise for her. Clinton said it was a remarkable experience “meeting the newly elected chief minister, a woman, who on her own started a new political party and built that political party over many years, and just successfully ousted Communist Party that had been in office for 30, 34 years or so, and who is trying now to govern a state with 90 million people in it”.

At the meeting in Writers’ Building, Clinton is believed to have promised liberal investments into Bengal if Banerjee eased her stand on issues critical to the US, mainly FDI (foreign direct investment) in retail and insurance. “You take one step and we’ll take two,” she is believed to have told her. Clinton may yet succeed in doing what many Indian leaders have not been able to do: Convince Banerjee to co-operate on crucial national economic decisions.

“There was a clear hint from Clinton that if Mamata allows FDI in retail and insurance, then US will certainly ensure flow of FDI into Bengal,” said a person close to Banerjee.

Within a week of Clinton’s visit, a co-ordination committee led by state chief secretary Samar Ghosh and US ambassador Nancy Powell began working overtime to draw up concrete proposals. A business delegation will visit the state sometime in early June following which a state delegation will visit the US in search of business opportunities. “If there is a firm commitment for investment, Mamata will also visit the US sometime this year,” the person said. But progress is likely to be slow as Banerjee is always worried about political fallouts.

“Be assured that Mamata will not make any concessions before the Panchayat elections due in 2013,” said a senior cabinet minister.

For Mamata, allowing FDI in retail and insurance will not be an easy task as it will give the Communists enough ammunition to attack her where it hurts the most. “Rural voters get easily swayed by the fear of losing their livelihoods. The bogey of losing jobs if international retailers come into the market can really hurt Mamata [in the elections],” the minister added.

The government, however, is taking the idea of attracting foreign investment into Bengal seriously and state Finance Minister Amit Mitra is preparing a policy on FDI investment. For Bengal, which is keen to tap one-fifth of India’s IT revenue by 2014, will need serious investment in that sector and the government is preparing a road map which they believe will lure huge investment very soon.

Private capital, however, is not easy to attract without appropriate policies and a robust state economy. The TMC supremo has banned new special economic zones in the state and has said she would not allow acquisition of farm land for industrial purposes. She has directed co-operative banks in the state to not dispose of farmlands collected as collateral even if there is a default. The farm economy in the state is in a crisis that is increasingly driving farmers to moneylenders. Reports of debt-ridden farmers committing suicides are increasing.

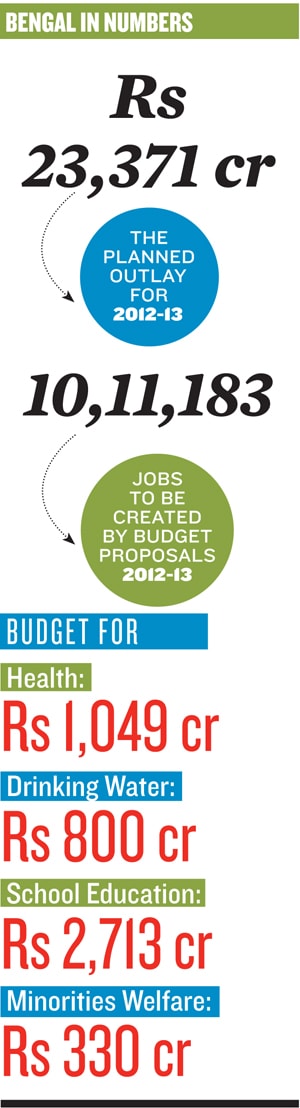

The state itself is groaning under a debt burden. As of March 31, the state’s outstanding liabilities stood at Rs 2.08 lakh crore compared to Rs 1.87 lakh crore the previous year. Budget estimates suggest the number would be Rs 2.26 lakh crore by the end of the current fiscal year. Most of the state’s revenues go into interest and salary payments. Mamata Banerjee has demanded a three-year moratorium on interest payments, saying most of the debt was incurred by the previous regime. Bengal’s annual interest payment of nearly Rs 21,000 crore almost equals the planned outlay of over Rs 23,000 crore for 2012-13.

The Central government has agreed to consider the request if Bengal comes up with a fiscal consolidation plan with clear milestones, but Banerjee does not want to commit. She believes that the powers in Delhi would have to relent as her party’s 19 members in Lok Sabha are crucial for the survival of the UPA government. Pranab Mukherjee stressed in Parliament on May 16 that he cannot give special concessions to Bengal but also said the ministry is working on an economic package for debt-laden Bengal, Punjab and Kerala.

Amit Mitra says the state government has a plan but declines to elaborate. Mitra says tax collections have improved and he is working on a proposal to attract investment into roads, ports and warehouse chains. Bengal prefers investments into service industries rather than manufacturing that require large tracts of land. It is laying out the red carpet to IT companies. It is trying to lure back Infosys which is planning to walk out after being denied SEZ benefits. However, others such as Cognizant Technology Solutions are upbeat.

“We are pleased with our experience in Kolkata,” Subho Samanta, Cognizant’s senior vice-president and head of Kolkata operations, said recently after the company unveiled plans to invest an additional Rs 200 crore to build the second phase of its software development centre on a 20-acre campus at Bantala SEZ.

Bengal recently reformed its land laws and that has largely been welcomed by industrialists even though it has some stringent provisions on land use.

“There had been some genuine move by the government to smoothen nerves, especially with the way government handled the Hillary Clinton visit, and now with this land reforms things look more positive for the state,” said an industrialist on condition of anonymity.

The biggest relaxation in the Act is removing the 24-acre cap on individual holdings. Now more land can be leased with state approval.

After the new law came into force, Banerjee told reporters, “Even before taking charge of the government, my party was termed as anti-industry. But we are trying to solve one of the biggest hindrances to development of industry.”

Even though her struggle for power was over a year ago, Banerjee has continued in the street fighting mode for the past year. She has made every effort to rub out the state’s Communist past from mind and matter. She has deleted Karl Marx from textbooks and banished the colour red from Kolkata, repainting the city white and blue. TMC leader and State Food Minister Jyotipriya Mallick asked party cadres not to marry CPM workers. Yet, it is difficult because though Banerjee is anti-CPM, her ethos is essentially Marxist.

Banerjee is now focussed on dominating grassroots politics by capturing as many panchayats in the elections next year. But she also has to find a balance between politics and administration. So far she has barely paid attention to it. Perhaps after the elections, she will. After all, there is a state to run.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)