Budget 2019: Farmers want loans, not just waivers

Apart from agricultural loans, farmers in Marathwada also want general loans to develop their farms and start small businesses

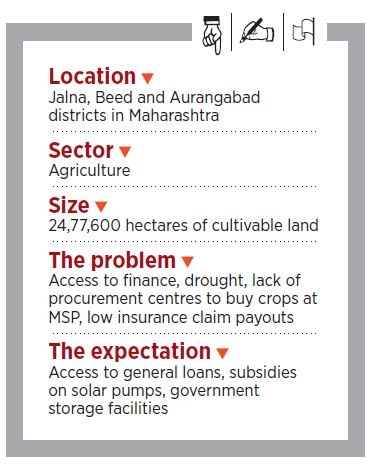

For four years, Marathwada has been reeling under drought, with 2018 being the worst

For four years, Marathwada has been reeling under drought, with 2018 being the worst Image: Satish Bate / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Farmers of Marathwada have a term for how they use bank crop loans disbursed during the July-October kharif season—“Nava juna”, meaning ‘new old’. They take the new loan to pay off their old loan, which they had taken the previous year from the shopkeeper of the store from which they buy seeds, fertilisers and the like.

Bank loans usually come too late for sowing purposes. Besides, farmers get only agricultural loans from banks. But since agriculture is reliant on the vagaries of nature, they also want general loans to develop their farms or start small businesses. Farmers want these loans to be based on their land value and proposals to develop their farms, rather than having banks think they will eventually seek loan waivers.

Banks, say farmers, do not entertain them for anything other than agricultural loans. “If a villager has 10 acres of land, the bank can mortgage his land and give him a loan of, say, ₹25 lakh to develop his farm as he pleases, and do some side business,” says a farmer from Georai taluka in Beed district. “Give us the money, without telling us how to build something or which buffalo to buy,” adds another farmer. Some have managed to use government subsidies for installing drip irrigation systems or for digging ponds; but the subsidy amount comes only after the irrigation system or pond has been built.

In a good monsoon year, farmers wouldn’t even think of having loans waived. But for the past four years, the region has been reeling under drought, with 2018 being the worst—it received only about three days of rain, as against the normal of 25-30 days. Acres of dry farmland stand barren, with most farmers skipping the rabi crop (sown in mid-November), or sowing only a part of their land.

*****

Gangaram Bandurao Kapsi, whose family has 25 acres, took a bank loan of ₹3 lakh to dig a well a few years ago. Today, it has doubled to ₹6 lakh, and there is no way he can repay it anytime soon. “I used to produce nearly 50 tonnes of sugarcane each year, but right now there is nothing to sell. I am growing food only for personal consumption,” he says, adding that he cut down 4 acres of sweet lime trees in 2017 because of the drought.

In 2014, the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana was approved with an outlay of ₹50,000 crore for a period of five years (2015-16 to 2019-20) to extend irrigation coverage and improve efficiency of water usage. In Marathwada, the scheme is also focussed on sugarcane farmers, and the state government made drip irrigation mandatory for the water-guzzling crop in July 2017.

Lack of water, and the need to build conservation and storage systems are not limited to drought-affected areas, and will remain a major demand in other regions too, says Milind Thatte, an activist who works with tribals in Palghar district. “The ground water is at good levels in the Konkan region, but it is difficult to reach it because of the terrain. So the government has to intervene.”

Another area that requires intervention and can help increase a farm family’s income, according to Thatte, is a farmer’s ability to sell seeds. “There should be a national seed production mission, where the farming sector can get indigenous, good quality seeds produced by farmers. If a small farmer is, say, farming onions, and the market falls, he can grow onion seeds and make money by selling them the following year. So, for a huge chunk of small farmers, seed production can be a great boon,” he says.

*****

In Marathwada, farmers are also facing a kharif crop loss. The Indian Meteorological Department had forecast 100 percent rainfall in 2018, and farmers had planned their sowing accordingly. “I faced losses because of that,” says a farmer in Padali village in Badnapur taluka of Jalna, who lost all the money he had invested in sowing.

Although crops are insured and premiums are deducted from the crop loan amount, the claims paid out, say farmers, are too little. “The insurance should at least cover the crop loan,” says Harishchandra Surashi, a farmer from Pagirwadi village in Jalna district.

Marathwada received only about three days of rain in 2018, as against the normal of 25-30 days

Marathwada received only about three days of rain in 2018, as against the normal of 25-30 daysImage: Kunal Patil / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Surashi and others list the approximate cost per acre of growing cotton: ₹2,000 for seeds, ₹3,000-4,000 for fertilisers, another ₹4,000-5,000 for pesticides, ₹3,000 for weeding, and ₹8,000 for picking. These add up to ₹20,000-22,000 per acre. The yield varies from 8 to 10 quintals per acre. With a minimum support price (MSP) of around ₹5,400 per quintal, in a good year they would recover the input costs, but in 2018, says a farmer, his yield was 2 quintals per acre.

The government is mulling three options to help alleviate the crisis: A revamped crop insurance scheme, a direct income support plan, and a cash handout to cover the difference between the sale prices and the MSP.

Shweta Saini, senior consultant at Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, says the monthly income support option works the best right now as a quick fix, because loan waivers only benefit those farmers who have taken loans from institutional lenders. A 2016-17 study by the Nabard All India Financial Inclusion Survey found that only about 30 percent of farmers who take loans, do so from institutional lenders. Saini adds that monthly income support has to be targeted well, after correctly identifying beneficiaries. When it comes to paying the difference between the sale price and MSP, there is a possibility of large-scale rigging, she says.

*****

With no government procurement centre for maize in Aurangabad district, farmers often end up selling to traders at prices lower than the MSP. A ‘producers company’ of farmers, set up by the NGO Savitribai Phule Mahila Ekatma Samaj Mandal (SPMESM) in 2016, helped farmers get the same rate as, or better than, the MSP, in 2018, says Yogesh Singare, an agronomist with SPMESM. The idea is to work towards a farm economy, where the overall farm income goes up, rather than a crop economy, which is focussed on how much a single crop is earning, adds Suhas Ajgaonkar, secretary, SPMESM.

Crop warehouses, subsidies for solar powered pumps and a pension scheme for farmers with a lower retirement age are some of the other concerns they want addressed. The Kisan Urja Suraksha Evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan, a ₹1.44 lakh crore scheme proposed in Budget 2018 provided for 17.5 lakh off grid solar pumps to begin with, according to Minister of Power RK Singh.

But the basic problem remains: The inherent bias against the farmer, and declining farm incomes. “Farmers need to be looked upon as businessmen. A businessman buys at wholesale prices and sells at retail, while a farmer buys at retail prices and sells at wholesale. To look at it as a businessman, we need to give them a conducive stable environment,” says Saini. “The bias towards consumers is inherent... it has to be neutralised.”

The prices of fertilisers, pesticides and seeds have gone up, but not the price of produce. “A bag of fertiliser that cost ₹700 four years ago, today costs ₹1,300. Whereas the rates of maize are the same,” says a farmer. “Only our produce has no worth.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)