Jalabala Vaidya and Gopal Sharman: A president, a Beetle and a play

About half a century ago, Jalabala Vaidya and Gopal Sharman, founders of New Delhi's Akshara theatre, started their journey in drama. Here's their story, divided into a few enthralling acts

“The presidential Rolls Royce pulled up at the back entrance of our house in Bengali Market,” says Jalabala Vaidya, co-founder of New Delhi’s Akshara theatre, recalling her first performance on a big stage—and it would be fair to call Rashtrapati Bhavan that. The car belonged to the then President of India, Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. It had come to pick the actress up from her home.

Earlier that year—in 1966—Radhakrishnan had undergone a cataract operation because of which he was unable to read, she tells us. But he wanted to catch up on playwright and poet Gopal Sharman’s work. “Professor Radhakrishnan used to enjoy Gopal’s writing in The Sunday Standard,” she tells ForbesLife India, so he invited Sharman, Vaidya’s husband, to Rashtrapati Bhavan to perform. “However, because of some carelessness on the part of the staff at Rashtrapati Bhavan, when it came to the day, I was invited and Gopal wasn’t,” says Vaidya. So the couple entered the car and Sharman dropped Vaidya to the imposing presidential house. “I still remember watching him walk down the Rajpath slope,” she says.

When she entered, Vaidya recalls, the president, looking perplexed, inquired, “Where’s the poet?”

Seated in a sun-soaked living room on the first floor of Akshara theatre, Vaidya, 79, is immersed in nostalgia, taking us on a journey through her memories. These promise to be more colourful than dull sepia. After all, though their fame has waned, at its peak, in the 1970s, both Sharman and Vaidya were internationally celebrated artists. At home, they were courted by Delhi’s upper echelons. Think politicians, bureaucrats.

Their renown reached the world stage on the back of a play based on Sharman’s interpretation of the Ramayana. Originally written for a full cast, a disagreement with the actors left them without anyone to work with. In retrospect, it was a blessing in disguise. Sharman moulded the script into the form of a katha, the traditional Indian storytelling format. Vaidya performed it as a solo act for the first time in 1970 for a small audience in a space located above the porch of Ashok Hotel in New Delhi’s diplomatic enclave.

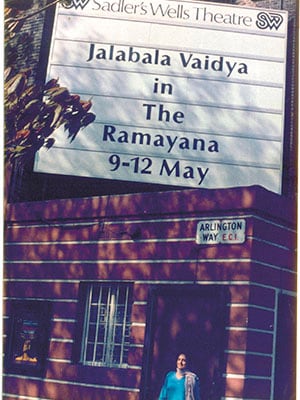

It has since been staged more than 2,000 times over 45 years. The play took the couple and their young daughter, Anusuya, to London’s West End, the Smithsonian in Washington DC and even Broadway and the United Nations headquarters in New York.

They filled the theatres, were adored by the Indian and foreign press, and received the kind of recognition that would make a film star blush. After a performance of The Ramayana in Portland, Oregon, The Oregon Journal reported: “One of international theatre’s very few inspired couples worked strong magic tonight. Gopal Sharman and his actress wife Jalabala Vaidya are possessed of genius.” The New York Times famously referred to their play as “India’s gift to Broadway”.

This, however, was still a few years away. At this point in our conversation, a president was watching.

At home: (Left) Vaidya and Sharman inside the wood-panelled Akshara theatre

One-way tickets

At Rashtrapati Bhavan, after explaining the mix-up to the president, Vaidya proceeded to perform Full Circle for a room full of dignitaries. “The president would make a few interruptions to explain the references that Gopal’s writing made to the Upanishads and Vedanta.” Later, Radhakrishnan called the head of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) and insisted Full Circle be staged at the Azad Bhavan Auditorium which is located near Pragati Maidan in Delhi.

On January 13, 1966, the couple staged its first-ever public performance. Full Circle was a dramatic recitation of stories and poems with strong philosophical underpinnings. “They were told through the voices of regular people,” recalls Anasuya, who is also the technical director of Akshara. Vaidya would perform and recite the stories and poems, while Sharman, who is a classically trained singer, would sing some of his favourite songs. “These ranged from Mira bhajans to songs written by Muhammad Iqbal,”

says Anasuya.

The performance at Azad Bhavan had important individuals in attendance, including several European diplomats. After it concluded, the ambassadors of Italy and Yugoslavia both invited the duo to perform in their respective countries. “We were delighted,” says Vaidya. However, with this news came the first of many challenges. The cost: The ICCR refused to pay for their travel expenses.

By this point in the conversation, Sharman, 80, dressed in a crisp, red kurta, has joined us. They now take turns in telling parts of the story, and interrupt only to embellish the other’s account with little facts or humour. After listening to our conversation, Sharman adds with a reflective smile, “It wasn’t that the tickets were very expensive, it’s just that we had no money.”

Vaidya travelled to Mumbai (then Bombay) to raise money for the tickets. Air India agreed to provide them with one ticket, but there was an odd condition. They were to print brochures that carried Air India advertisements and distribute them among people they knew, Sharman tells us. While he printed the brochures, Vaidya arranged the money for a second ticket. “There was none of this anti-immigration fuss,” says Vaidya. “So we just bought one-way tickets [to Rome].”

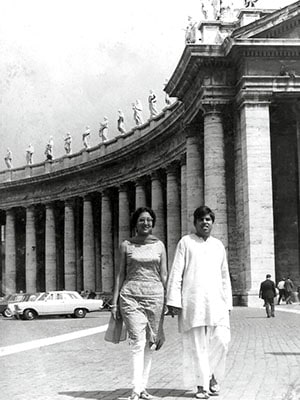

In Rome, the beauty of the city contrasted with the dull, academic look of the space at the Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East (IsMEO), where they performed. It was here that they met “a very nice lady named Mrs Riley, who invited us to perform at her theatre”. Mrs Riley ran the Teatro Goldoni theatre, a more aesthetically appealing venue.

In the interim, they had to travel to Yugoslavia, where, says Vaidya, “I must admit, we had a rather good time, eating and drinking, and drinking.” After one of their performances, at a dinner party, Vaidya remembers, a man raised a toast to her, yelled “La Bella!”, drank from his glass, and smashed it on the floor.

They then returned to Rome and to Teatro Goldoni which, Vaidya tells us, usually hosted performances in foreign languages. So when they arrived at the theatre, they weren’t surprised to learn that another English language performance was to be held on the same day as theirs. “Joan Baez was to perform on the same day!” says Vaidya. “I was a fan,” she confesses. They met the legendary American singer, and then proceeded to perform Full Circle later that day. “The next morning when we saw the Italian papers, we were huge, and there was a small mention of Baez,” she says. “And that’s the story of how we really began.”

London calling: Vaidya and Sharman along with invitees to their performance at the Indian embassy in London in 1968

A Little Black Car

It would appear logical that they came back from Italy after this. But “no, we didn’t return! Why should we?” asks Vaidya, with mock incredulity. Their good fortune in Rome continued.

They performed for a group of Jesuit priests, followed by an audience with Pope Paul IV. They were then invited to perform on television by the Italian public broadcaster. After the broadcast, Vaidya remembers that the officials were “awfully squeamish and apologetic. They said that they were sorry that they wouldn’t be able to pay us too much money.” However, “when they actually paid us, it was so much money,” she laughs.

It was, in fact, so very much that they went across the road to a used car salesman and bought a black Volkswagen Beetle. “In its later years, the car would often break down or simply refuse to start,” says Anasuya. English actress Vanessa Redgrave and a serving Qatari ambassador to India were among the many distinguished personalities over the years to get off and push that car, she adds.

Staying with Beatles, Sharman and Vaidya were also introduced George Harrison a few years later. “He wore a huge fur coat and it made him look very thin and scraggly. He seemed very cold and distant,” says Vaidya. “I don’t know why, but we didn’t click with these popular icons that we would meet,” she recalls, referring to another chance meeting, this time with rock band Pink Floyd. This was a time when Western musicians were enthralled with all things Indian—it was the ’70s, after all. “[But though] they may have experimented with Indian musical instruments, philosophy and so on, it’s not certain that they understood it,” says Anasuya, explaining the disconnect felt by Vaidya.

From Rome, the two drove to Munich, and after another lucrative television performance for Bayerischer Rundfunk (Bavarian Broadcasting, BR), they headed to London. “You see, Jalabala was born in London,” says Sharman. “I was born in Calcutta, and had come to believe that the British were terribly racist towards Indians.” In short, says an amused Vaidya, “Gopal thought that he was going to be refused entry into England.” When they arrived at the dock, Sharman confesses to being pleasantly surprised at being welcomed by the authorities.

This is where they finally settled down for a while. They continued to perform both in London and in Europe. One of these performances, at a theatre in Brussels, was arranged by a young diplomat they had met in London. His name was Mani Shankar Aiyar.

In London, Sharman also began writing reviews and opinion pieces for The Times. While there, the couple staged their show, Full Circle, at the now-defunct Mercury Theatre on Notting Hill. This performance brought some good news. “The Royal Shakespeare Company asked us if we would like to stage a play at their World Theatre Season,” says Vaidya. While the play did not make it to the season for a variety of reasons, including an actors’ strike and the 1971 war, this was the beginning of The Ramayana. It seems the Tatas got news of this development and awarded Sharman the Homi Bhabha Fellowship to assist him financially in staging the play.

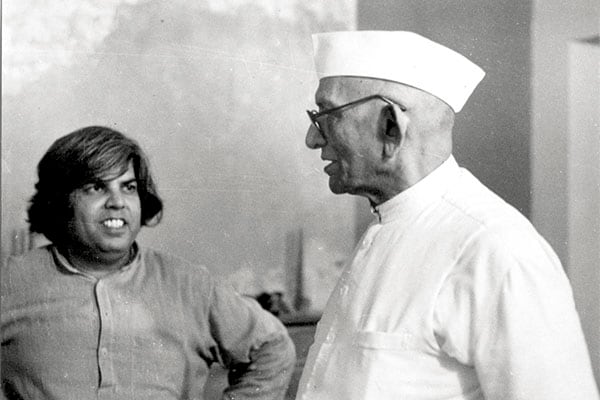

At the end of their two-year sojourn, Vaidya returned just in time to attend Anasuya’s birthday; her daughter had stayed on in India with relatives. Sharman returned to India shortly after. Now they needed to find space where they could begin rehearsing the play. At this juncture, they found an unlikely ally in Morarji Desai, who was deputy prime minister at the time; he was responsible for the allotment of land on which Akshara stands today.

For Anasuya, Full Circle was so much about just the two of them—her parents. “They were always complete in each other,” she says. As they went along, they added more people, including family and actors. But the core was, and still is, the two of them. “That has remained constant,” she says.

Even in the retelling of their story, seated in their living room decades since the first performance, their roles seem unchanged.

“When I met Gopal I liked him because he was fun. He liked making jokes,” says Vaidya. Almost on cue, Sharman chimes in: “When we were driving in Germany,” says Sharman, adding with peals of laughter, “the exit signs on the highway read ‘Ausfahrt’. Aus...fart!”

They first met one evening when Vaidya was working at the Delhi-based Link magazine and Sharman had just begun writing for them. “We were the only people on the floor and I could see a silhouette of him through the several glass partitions that separated us,” she recalls. Vaidya was supposed to edit the copy that Sharman was writing, and he was late. “So I had a note sent to him asking him how long he was going to take,” she says. In a manner that would not be surprising had she known him, he wrote back, ‘Don’t hit the roof, don’t go through the floor’. Infuriated, she walked over to his workplace, “And

as soon as I saw him, I fell in love with him.”

Image: Courtesy Akshara Theatre Archive

Sharman with former PM Morarji Desai at Akshara theatre

Chance Encounters

Back in their living room, Sharman quickly moves to another amusing episode from when they performed The Ramayana at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London’s West End. “It was a huge theatre, and I remember being worried about whether the size would diminish the impact of a solo show.” On the final day of the show, it was raining outside. “London had a lot of Indian millionaires, and they all expected to be invited to the play,” he says.

However, their profits were tied to how many ticket sales they made. “So why would we give them to anyone for free?” says Sharman. He recalls looking down from a window with amusement at the bevy of wealthy Indian businessmen waiting outside the theatre. One of them was a man who later went on to become the deputy speaker of the House of Lords, Swraj Paul. Paul later invited them over to his home and they remained friends for some time after that.

The journey that began as a youthful joyride had by now become less uncertain. This, however, did not hamper the inherent dramatic nature of their story. Problems would prop up, but solutions would be at hand, more often than not in the form of a Good Samaritan who would emerge, appropriately, from their audience.

And that’s how they finally reached Mumbai in 1981.

Although Sharman had written The Ramayana after receiving the Homi Bhabha Fellowship grant, they had never staged the play in Mumbai. “One day, TN Kaul, who was then the Indian ambassador to the US, suggested that we perform at the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai,” says Sharman. Even though they wrote to NCPA indicating an interest in performing, they did not get an immediate positive response.

Call it serendipity, but it was also around this time that Kaul invited actors Sunil and Nargis Dutt to watch The Ramayana at Akshara. Following the performance, the Dutts insisted on paying for the play to be staged at the Tata Theatre in NCPA. “We played for 10 days straight,” says Sharman, triumphantly.

During these performances, another pleasant consequence of not reserving seats resulted in a chance meeting with a man, who, as Anasuya remembers it, “had beautiful, twinkly blue eyes”.

The events occurred in the same random manner as they had in their early days. “After one of our shows, a car arrived to pick us up and took us to Bombay House,” says Sharman. JRD Tata greeted them there and, over tea, explained to them that although he hadn’t watched the play, it wasn’t because he did not want to. “He had sent his driver to buy tickets but only the cheap seats were being sold in ‘black’ outside.”

An Old Master

Cars still pull up, but now they do it to bring in audiences for the performances at the theatre rather than to transport them to their next adventure. Because, although Vaidya and Sharman don’t perform as often as they used to, the Akshara repertory continues to stage plays frequently. It also plays host to several independent theatre groups, musicians and even a growing number of stand-up comics.

Akshara, which was founded in 1972, is also home for the couple. It was built in phases over the next decade by Sharman and his team of craftsmen. “I didn’t just order people around,” he says. “I built this with my own hands.” The theatre lies on about an acre of land near the Gole Dak Khana in central Delhi. The two-storeyed building houses an intimate 96-seat indoor theatre, while a larger 300-seat amphitheatre is located at the back of the property. The wood-panelled walls, elegant chairs and intricate carvings on the building’s outer façade all bear marks of Sharman’s artistic genius.

Of late, a rise in demand for affordable performance spaces in the national capital has brought the spotlight back on the theatre. “Akshara has a very special place in Delhi theatre today,” says Aishwarya Jha, 24, a Delhi-based actor who has been visiting the theatre since she was a child. “You can always count on finding the best of both fresh talent as well as old masters on its stage. Akshara itself is one of the last old masters left standing.”

But whether you catch a show there, or not, there’s one sight that you shouldn’t miss: Two people, a man with a strikingly thick head of white hair alongside a tall, elegant woman sitting together. They can sometimes be seen strolling in the garden which lies between the main building and the open-air Pipal Tree theatre, or lounging in their veranda which overlooks the garden. It is, however, more likely that you’ll see them inside the theatre, watching a play, directing or, occasionally, even performing.

Wherever it is that you see them, there is an almost indescribable quality to the sight that is at once arresting and comforting; the sight of two people living in a world that they have created, together.

(This story appears in the Sept-Oct 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)