Braving the roads in the Himalayas

Fifty-eight bikers thundered out of New Delhi for the Himalayas banking on their untapped reserves of fortitude and courage. But only 27 completed the circuit. And one discovered the deeper meaning of love

The waterfall was not meant to be, its existence an anomaly no one could explain. Our guides insisted that it was not there last year. But it was flowing down a hill now, and across my path, magnificent in its ferocity unlike the many water crossings I had encountered earlier in the route since leaving Kaza in the Spiti Valley of Himachal Pradesh. I was among the 58 bikers trying to reach the Himachal village of Jispa in the Himalayas, where the terrain always seemed to be changing. Having left the nearest village far behind, we could not turn back.

The first rider accelerated his bike—hands off the clutch and brake, a prayer on his lips—and made the crossing. A few others followed with some difficulty. Under the unusually warm afternoon sun, the mountain ice was melting faster than ever; the force of the water flow was increasing with every passing minute. As it rushed and swirled past my bike, I could see this water body that was not meant to be dislodge football-sized rocks from its path.

It was impossible to map a safe route. Many bikers found themselves stuck between massive rocks and had to be pushed by fellow riders who had no alternative to standing knee-deep in freezing water. Some bikers fell, and a few were simply scared to cross to the other side. Four-and-a-half-hours later, the last motorcycle made the crossing even as darkness enveloped the Valley.

And then it rained.

Stretching across 2,400 km and spanning six countries—India, Nepal, Pakistan, China, Bhutan and Afghanistan—the Himalayas demand to be conquered. Their existence is an exaggeration, a hyperbole of the natural world. The mountain range, which separates the Indo-Gangetic Plain from the Tibetan Plateau, has over a hundred peaks, including Mount Everest, which towers over the world at a height of 29,029 ft. The Himalayas are home to 15,000 glaciers; they are the birthplace of three of the world’s largest river systems, the Indus, the Yangtze and the Ganga-Brahmaputra; they have the third largest deposit of ice after the Arctic and the Antarctic, and stores as much as 12,000 cubic km of fresh water in its vast expanse. The range has earned the moniker, Third Pole.

For centuries, the Himalayas have inspired adventurers to tame it; Mount Everest alone has claimed the lives of more than 200 ‘known people’ since 1922. But perhaps New Zealander Edmund Hillary, who, along with Nepalese Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, was the first to climb the world’s highest peak in 1953, got it right when he said, “It is not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves.” This was the lesson that the motorcyclists who participated in the 12th edition of the Himalayan Odyssey 2015 learnt over a fortnight, from July 11 to July 26, as they traversed some of the more treacherous but stunning routes through the mountains. I accompanied them for the first leg of the journey from Delhi to Leh.

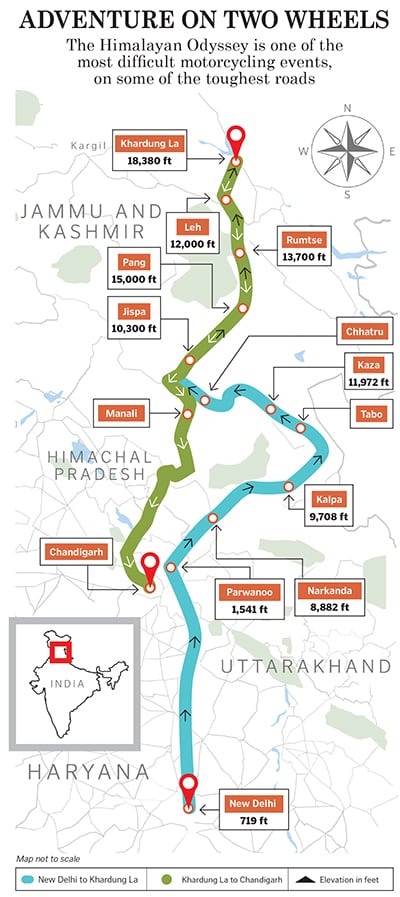

Organised by Royal Enfield (a division of Eicher Motors and the largest player in the Indian leisure bike segment), the Himalayan Odyssey is one of the most challenging adventure motorcycling events of the year. It takes riders across three mountain ranges, six passes (including two of the highest in the world, Khardung La at 18,380 ft and Taglang La at 17,582 ft), one of the world’s highest deserts in the Nubra Valley and a flat stretch of a 43-km-long road set across the barren landscape of Moore Plains in Ladakh.

This year, the Odyssey started from Delhi and participants rode through the Union Territory of Chandigarh, Parwanoo, Kalpa, Kaza and Jispa in Himachal Pradesh, and Rumtse and Leh, the highest desert city in the Himalayas, in Ladakh. On the return journey, the ride took the Leh-Manali Highway and concluded at Chandigarh after the riders had traversed 2,280 km.

Barring a few patches of well-paved stretches, the journey is off-road riding at its most daunting. It snakes through what avid riders call the “Mecca of endurance motorcycling”—the Spiti Valley. “Terming the route treacherous is a terrible understatement,” says Sachin Chavan, head-rides & community, at Royal Enfield. “The elevation profile is steep. The bikers start at almost sea level in Delhi and then ride up to 18,380 ft on roads that barely exist.”

The Himalayan Odyssey tests the limit of the riders’ physical and mental endurance. More often than not, participants are cut off from the trappings of civilisation and communication. No emails, no cellphones, no land-line connections. I travelled through virgin terrain untrammelled by human settlements. The occasional sighting of a lone man tending to his yak

was comforting.

Each participant rode a Royal Enfield. Most were more at home in the corporate world as employees or entrepreneurs, a few held government positions and some were from the Indian Army. All were united by their passion for off-road biking, happy and willing to pay the Rs 40,000 entry fee that covers logistics, stay and support. A few like 37-year-old Delhiite Ritesh Mehra, a captain with the Merchant Navy, had participated in the event before, but several were new entrants.

“You go up the mountains as a rider, but come back as an explorer,” said Rudratej Singh, president, Royal Enfield, as he flagged off the Himalayan Odyssey 2015 at India Gate in the capital on a wet Saturday morning.

As we thundered towards the Himalayas, Edmund Hillary’s pithy quote on conquering oneself became a reality. “The foremost learning is conquering the fear of the unknown,” says Major Shantanu Krishna (retd), a resident of Gurgaon. “We start out on the road every day with a plan, but have no idea what to expect when it comes to the nature of the terrain or the weather.” Krishna, 35, who runs a business risk consultancy, decided to participate in the rally as he was missing the bustle of his army days.

He got what he had bargained for. “In the army, we always say no one can be branded brave or called a coward,” he says. “Circumstances determine that. This ride brought out the bravery in each and every rider as it gave him the opportunity to

overcome fear.”

Bravery aside, the Himalayas also imparted numerous lessons in patience, acceptance and the futility of changing forces beyond our control. For instance, in the mountains, the weather is a fickle friend and can have far-reaching consequences. Think rain, hailstorms, the occasional snowfall, and their aftermath: Landslides, flash floods, swollen rivers and innumerable water crossings.

This is a lesson we learnt every now and then as the sun and clouds played hide-and-seek. On the third day, for instance, we were manoeuvring our bikes in agonisingly slow movements over slushy pebble-ridden slippery roads between Jeori and Wangtoo—a stretch where most of Himachal Pradesh’s hydropower projects are coming up.

The following morning, we tackled a particularly difficult stretch between Kalpa and Kaza in the Spiti Valley. It involved riding our bikes for 210 km, most of which was off-road through areas whose names were unfamiliar on my tongue: Jang, Spello, Pooh, Chango, Sumdo and Tabo. Narrow roads with slippery pebbles and steep cliffs marked most of the terrain. By early evening, the exhausted bikers were keen to reach civilisation… and Kaza.

But as the group crossed Tabo and headed towards Schichling, the last Himachal village before Kaza, a landslide cut off the road. After a frustrating wait for an hour, we decided to return to Tabo and hunt for accommodation for 70-odd people, including the support staff that manages logistics, a doctor for the riders and a few mechanics. “Spiti Valley is notorious for landslides, which can upset even well-planned schedules,” says Mehra.

Fortunately, Tabo village has around 50 houses with homestay options. It is also home to the ancient Tabo Monastery, the oldest functioning Buddhist temple in India that dates back to 996 AD and which is famous for its exquisite wall paintings. All the houses in the village display colourful flags with the Tibetan mantra, ‘Om Ma Ni Padme Hum’, printed on them. In the mountains, the violence and peaceful facets of nature—the calm of a cold night and the destruction wrought by a landslide—are within a whisker of each other.

“The people who live here barely have any roads, transportation facilities, electricity or even a proper livelihood but they seem content and smile all the time,” remarks aspiring actor Karan Puri, 25, who rewarded himself with this ride after completing a course in theatre in Mumbai. And such a philosophical thought isn’t unusual in the Himalayas.

Much like the terrain, the Himalayan Odyssey too is a curious blend of aggression and humility.

To thrive in such a setting, participants have to be mentally and physically fit. “Bikers have to handle the stress of riding, be alert for altitude sickness and hypothermia and adapt to low oxygen levels,” says rider Dr Deepak Chauhan, assistant professor (ear, nose and throat) at Pramukhswami Medical College in Anand, Gujarat. “Altitude sickness is the biggest threat. You have to keep drinking water. Acclimatisation is critical.”

During the journey, one rider suffered from altitude sickness. He was immediately moved to a lower altitude, first to Leh and then to Delhi. (If left unchecked, the symptoms of mild altitude sickness—headache, nausea and vomiting, shortness of breath and increased heart rate—can worsen and become life threatening.)

“Two hundred kilometres in the mountains is equivalent to 600 km in the plains. The ideal riding distance before fatigue sets in and hampers reflexes is 150 km,” says Chauhan. Before the rally, Royal Enfield put every rider through a fitness test which included running for five km, and completing 50 push-ups in a single hour.

Nothing, however, prepares you for the loneliness of riding along stretches of beautiful but sometimes desolate landscape, cocooned in your helmet with only the constant thrum of the Royal Enfield accompanying your thoughts. And sometimes, even the slightest distraction can have terrifying consequences. Two riders learnt that the hard way: One took an uncharted short cut and broke his leg and shoulder. Another lost his balance and dislocated his shoulder. The terrain is such that even the most careful rider will fall. What matters is how quickly you get up and continue. (Every rider had to sign an indemnity bond before the rally.)

Though the team of 58 seldom rode together—each set his own pace—members looked out for each other. No one overtook or passed by a stationary rider without a thumbs-up signal from him. If a bike broke down, the rider would wait for hours for the service truck to reach him. Often, a fellow biker would pull up and keep him company. “For hours you ride alone in a terrain that is bad and empty. The riders know that there is someone behind them just in case something happens. It is this implicit trust that keeps them going,” says Chavan.

This Odyssey taught Rohit Ojha the virtues of working as a team. “The way everyone came together when there was a difficulty (like a water crossing) was fascinating. They helped each other at the risk of catching hypothermia,” says Ojha, who works as an instrumentation engineer at Cairn Energy’s facility in Barmer, Rajasthan. Completing the Himalayan Odyssey was a dream for the 24-year-old, who had booked a Royal Enfield Classic 350 with his first salary. The ties that bound the man to his set of wheels strengthened with each passing day. “My connection with my bike has only improved and I know it better than ever,” says Ojha. Whenever he stopped to take a picture of the vast Himalayan landscape, he made it a point to include his bike in the frame.

This year’s Odyssey was particularly challenging due to weather-related and man-made disruptions. We lost a few days on account of landslides and another due to a bandh in Leh, called by the local taxi union against the proliferation of outstation taxis. The route had to be altered to factor in such delays. And the ride to Hunder in the Nubra Valley—home to the double humped Bactrian camel and Tso Kar Lake (a majestic salt water lake at 14,860 ft)—was dropped.

These disruptions had another effect: Not everyone completed the full 2,280 km. Fatigue and delays forced many to give up the ride and return to Delhi from Leh mid journey. Fifty-eight motorcyclists may have thundered out of Delhi, but only 27 completed the circuit to reach the last stop, Chandigarh.

Did they come back braver?

Well, Kunal Pandit, 32, returned more in love with his girlfriend than ever before. For the very first time in the 12-year-history of the Himalayan Odyssey, Royal Enfield allowed pillion riders. Not the one to miss an opportunity, the area sales manager at Samsung Electronics in Lucknow asked his girlfriend to be his pillion driver. “The ride was difficult with a pillion, but her confidence in me and my respect for her has increased,” says Pandit, one of the 27 to complete the circuit.

So it is then. In the mountains you can find courage, humility and, if you are lucky, even love.

(This story appears in the Sept-Oct 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)