Afghanistan: Emerging From The Rubble

India could play an anchoring role in transforming the country into a modern state but it must first work on the Gordian knot of contemporary geopolitics

There is no hint in Mahammod Khan’s boyish face and gentle demeanour that he is a member of Parliament from Kandahar, a province in southern Afghanistan where ordinary citizens have blind dates with violent death almost every day.

As he talks of leaving Kandahar for the relative safety of Kabul, Khan, a 30-something doctor of medicine, pours green tea into white china cups and leans back in his faux leather office chair that still sports remnants of a UNDP sticker. Suddenly he pulls out a paper from the desk-top printer and starts drawing a map of southern and eastern Afghanistan. He carefully sketches Helmand, Kandahar, Zabul, Khost and other adjoining provinces and then makes a large circle that includes parts of neighbouring Pakistan up to Quetta.

Then he looks up and says with a wan smile, “Here live the unfortunate Pashtuns.”

Within Mahammod Khan’s circle lies the Gordian knot of contemporary geopolitics, untying which will not only bring peace to Afghanistan but also alter international relations far and near. Here Pakhtunwali, the ancient code that guides its numerous Pashtun tribes, potently mixes with ultra-orthodox Islam and perverse interests of various states. While the Pakhtunwali ensures magnanimous treatment of guests, radical Islam enforces untrimmed beards for men and burqa for women. It is in deference to Pakhtunwali that Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar sheltered Osama bin Laden 10 years ago, despite knowing it would invite the wrath of the bald eagle.

The Taliban, a group of largely Pashtun tribesmen, belong to this region. All international efforts are now focussed on getting this group (there are, in fact, several groups with different agendas under the umbrella called Taliban) to give up arms and help save the country from total ruin. Insurgents, many reckon, are minuscule in number.

“The Taliban does not have more than 10,000 fighters. And they do not have much support of the people,” says Elham Gharji, chancellor of Gawharshad Institute of Higher Learning, a one-year-old private university supported by Afghan intellectuals, academics and politicians.

Yet insurgency is expanding despite the US-led efforts with guns and dollars, the traditional carrot and stick. After waging an exhausting war for 10 years, America wants to go home. So do its 48 allies in the International Security Assistance Force. Managing Afghanistan after 2014, when international forces are scheduled to leave, will be the main agenda of the upcoming Bonn Conference in December. A complete withdrawal in three years will be catastrophic.

“It will certainly be civil war,” says Hussain Ali Yasa, chief editor of the Afghanistan Group of Newspapers that published the Daily Outlook Afghanistan in English and Dari.

That is why the government is hoping the foreigners will stay until 2024.

“At the Bonn Conference we expect the international community to commit another decade of support but in a more clear and transparent way,” second vice president Karim Khalili told Forbes India in an interview at his heavily guarded Victorian-style office in Kabul.

In the milieu, the one country that seems to be close to the ordinary Afghan’s heart is India. It is also the only major nation with deep involvement but no military presence. India has committed $2 billion to rebuilding efforts. It has almost completed construction of a new parliament complex. It supports scores of small, community-based development projects such as building small bridges, digging tube-wells and providing vocational training to war widows in many villages, according to India’s foreign ministry. India also recently doubled the number of scholarships to Afghan students to 1,000.

In early October, in a widely welcomed move, India signed a strategic pact to train and equip Afghanistan’s defence forces. India also wields considerable soft power through its widely popular television soaps and Bollywood movies. Its influence in Afghanistan’s politics is still disproportionately small compared to Pakistan’s and the US’, or even Iran’s, but inching up slowly. At a conference in Istanbul in early November, India’s position as an important regional player in Afghanistan was affirmed by President Karzai.

Meanwhile, the mistrust of Pakistan is increasing. In fact, many, including senior government officials, hold Pakistan and the US responsible for the state of their country. One top official in the commerce ministry points out that despite signing a trade and transit agreement, Pakistan officials routinely harass Afghan trucks and traders on flimsy grounds.

“Pakistan has always used the border as a political tool, opening and closing it as a pressure tactic,” says Waliullah Rahmani, executive director of the Kabul Centre for Strategic Studies (KCSS).

The Lost Years

In the decade since the first Bonn Conference — held in December 2001 after America routed the Taliban, who withdrew to the region in Mahammod Khan’s circle — more than 50 countries have been involved in stabilising Afghanistan, with little success. The international community pledged a total aid of $90 billion, of which about $57 billion has been disbursed. Of that, $29 billion was spent on the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Police alone, says International Crisis Group (ICG), an independent organisation that works to prevent and resolve deadly conflicts across the world. But that is not enough.

“There is no possibility that any amount of international assistance to the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) will stabilise the country in the next three years unless there are significant changes in international strategies, priorities and programmes,” ICG warns in an August 2011 report. The ANSF was 305,600 strong by October and was to be ramped up to 352,000. However, talks are already on to scale down this number. A report released in October by the US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) says that its audits of contracts and programmes to provide infrastructure, sustain forces, and assess ANSF capabilities have repeatedly found problems related to costs, schedule delays, and sustainability.

Many believe that the international community’s strategy in Afghanistan was flawed from the beginning. “The international community doesn’t know what they are playing with and how,” says Rahmani of KCSS. “Each country is following its own national interest,” says Rahmani, a long-haired, boyish looking political science and strategic studies scholar from UCLA.

Former British Ambassador to Afghanistan Sherard Cowper-Coles writes in a recent book, Cables from Kabul, that the international community had no cohesive strategy. “In Kabul, the US embassy never succeeded in taking overall charge of the US effort in Afghanistan,” he writes. “One of the main principles of COIN (counter-insurgency), unity of command, is honoured more in the breach than in the observance.” All that after the US spending about $125 billion on Afghanistan every year, he says.

Earlier, when the hunt for Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda members was the most intense, the US shovelled millions of dollars to local warlords to fight as its proxies. Until 2010, only 18 percent of foreign aid was routed through the Afghan government.

The Development Cooperation Report 2010 of Afghanistan’s finance ministry concludes that “overseas development assistance delivery by-passing government budget channels results in missed opportunity of the Afghan government to learn by doing and thereby develop the required capacity to design, implement, monitor and report on development programmes”.

At last year’s Kabul conference it was decided that by the end of 2011 the proportion of assistance channelled through the government would increase to 50 percent. It still has not, and leakage is heavy.

A lot of international aid is spent on advising the Afghans. There are 282 advisors in the interior ministry alone, 120 of whom are contractors, absorbing a total of $36 million a year, according to ICG. In its logistics department, international staff reportedly outnumber the Afghans they advise by 45 to 14, it says.

Still, international funding has helped build 4,000 km of roads, get power supply to 30 percent of the country (against a mere 10 percent in 2001), and helped make steady progress in education.

There are now about 10,000 schools across the country. Enrolment in schools has gone up six times since 2001 and now stands at around 6.3 million, more than a third of them girls. Before 2001, the Taliban had banned girls’ education. Even now schools are frequently destroyed. In the third week of October two girls’ schools with a combined student strength of 3,150 in Nangarhar province were gutted by unidentified gunmen. Clearly, the initial strategy of ‘capture, hold, build’ is unravelling in many places, holding the country at the bottom of human development rankings and second among corrupt nations.

Recent World Bank estimates show that Afghanistan remains the lowest of low-income countries. More than half of its population of 29 million lives on $30 a month or less. There is no sustainable livelihood alternative, especially in far-flung provinces such as Uruzgan and Nimroz, to primitive farming. A large part of its GDP is made up of poppy farming, which is smuggled to other countries. Hardly any revenue from poppy cultivation reaches the government but a lot of it goes to enrich warlords and insurgents.

“The insecurity is rising. The overall graph of our system is going down and it will have an end point — total collapse,” says Daily Outlook Afghanistan’s Yasa.

Political Weakness

At the 2001 Bonn conference, India played a crucial role in installing Hamid Karzai as the leader of the interim government. India’s then ambassador to Afghanistan Satinder Lambah is said to have played a fine diplomatic hand in convincing the Northern Alliance to accept Karzai and then springing him as an alternative to the West’s choices. The Northern Alliance’s support gave Karzai, until then an unknown schoolteacher from an influential Pashtun family of the Popalzai tribe, the aura of pan-Afghan acceptance.

However, in the seven years he has been President, Karzai has steadily lost popularity and is viewed with suspicion by both locals as well as foreigners. He runs the government with warlords such as Fahim Khan in key government positions.

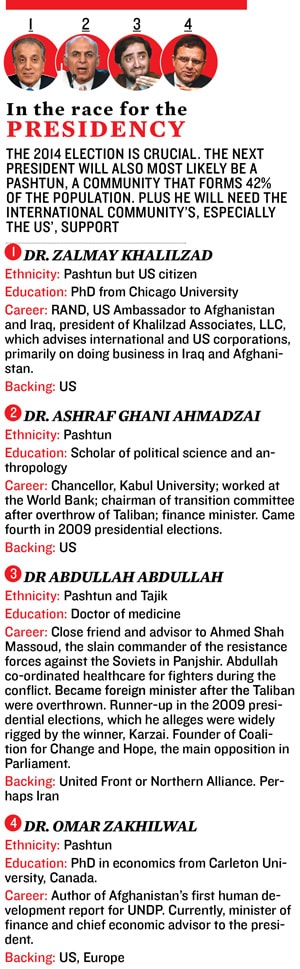

Karzai’s credibility was weakened further in 2009 when he was accused of rigging the presidential polls. Only US support and rival Abdullah Abdullah’s withdrawal from run-off polls kept him in office.

“In the first phase of his presidency, Karzai used the international community as a leverage against his internal rivals,” says Abdullah. “In the second phase he is provoking the local people against the international community using nationalistic and conservative ideas to give a sense of foreign occupation.”

In the second week of October, Karzai earned the wrath of parliament when he ordered police to forcibly remove a woman member from Herat province, Semin Barakzai, who was on a hunger strike in a tent pitched in the parliament car park. Barakzai began fasting to protest the Independent Election Commission removing her along with eight others from parliament membership. Some believe that Karzai ordered the police action at the behest of his deputy Fahim Khan to embarrass the interior minister Bismillah Khan, who could be a presidential candidate in 2014.

Videos of the police roughly removing her and pulling down tents were aired on television, inviting widespread condemnation. Even Karzai’s second deputy Karim Khalili called the police action ‘uncivil’. Barakzai continued her fast in the military hospital, where she was held for days, until tribal elders intervened.

Karzai has also used his sweeping powers to weaken other pillars of the state such as the judiciary. “Afghanistan’s justice system is in a catastrophic state of disrepair,” says ICG, in a 2010 report. The lack of a clearly defined arbiter of the Constitution has undercut the authority of the Supreme Court and transformed it into a puppet of President Karzai. The judges of the court are continuing beyond their tenure. “It is patently illegal,” says Abdullah Abdullah.

There are widespread corruption allegations against many leaders and government functionaries, especially those in the provinces. “Customs posts are routinely auctioned off for millions of dollars,” says Mahammod Khan. A single check post on the Pakistan border has revenues of anywhere between $100,000 and $300,000. “None of it reaches the treasury,” he adds. Despite improvement, Afghanistan’s revenues cover only 70 percent of the government’s operational expenditure.

/Road to Resolution

Afghanistan’s redemption lies in rebuilding its tattered economy by finding ways of increasing government revenues and channelling them towards development. The country does have a plan. It hopes to be the transit hub for oil and gas from Central Asia to South Asia and goods and services from South Asia.

It also wants to develop its vast mineral resources that are mostly concentrated in the Bamiyan province.

China is already investing about $10 billion in Ainak mines to extract copper. An Indian consortium led by the state-owned SAIL is on the verge of bagging a concession for mining high-grade iron ore from Hajigak mines in the province. The Indian consortium may also set up a steel factory nearby.

The US is backing a new Silk Route project that will imitate the ancient trade routes. India has built a 215-km highway from Delaram to Zaranj on the Iran border at a cost of Rs. 600 crore and 135 lives. It offers an alternative trade route ending at the Chabahar port in Iran that is also being upgraded with Indian help. But the environment is also too hot for Indian nationals.

“Five years ago I used to freely travel everywhere, alone. I cannot think of it now,” says Rajiv Wadhawan, who, as assistant general manager of joint venture BSC-C&C, oversees the construction of the Afghan Parliament building. Wadhawan has been in Afghanistan for seven years. He used to travel in a Scorpio to display a bit of national pride. “We had a fleet of Scorpios. But they are too conspicuous and therefore, risky now,” says Wadhawan, who has switched to a bullet-proof Toyota SUV. He doesn’t employ local security to protect the inner perimeter of project sites. “We bring ex-Indian armymen for inner circle security,” he says. The precarious environment is also forcing businessmen like him to think twice before accepting new projects. “I will take up projects only if the rates are that attractive,” Wadhawan says.

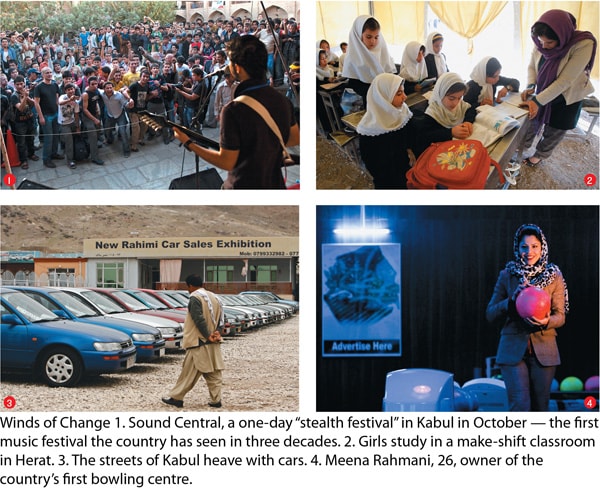

Images: 1. Ahmad Masood / Reuters; 2. Raheb Homavandi / Reuters; 3. Reuters; 4. Ahmad Masoodi

India’s involvement in Afghanistan rests on how well the foreign ministry is able to balance its relations with irreconcilable parties such as the Northern Alliance and the Pashtuns. It has to also manage its relationship with Iran, which wields considerable clout among the Shia Muslims, but is a sworn enemy of the US. Iran is now reported to even support the Taliban (Sunni Muslims who are traditional foes of the Shias) to fight the Americans, making it even more difficult for India to balance the two crucial relationships — with the US and Iran. The US, in fact, torpedoed an Afghan plan to have a tripartite strategic agreement with Iran and Pakistan.

In a recent paper written for the Aspen Institute, political commentator Ajai Shukla quotes former Taliban ambassador to Pakistan Mullah Zaeff as saying, “The belief in New Delhi that the Taliban are looking at India as an enemy… the conception of India always is not clear (sic). They are thinking that the Taliban are working for Pakistan and they are against India. This is not the reality. Why they (New Delhi) are not sitting with the Taliban? Why they are not meeting them, talking to them?”

Shukla says that India has an almost unblemished record of backing the losing horse in Afghanistan and should now begin talking to the Taliban with a long-term view. Officials in the foreign ministry say on condition of anonymity that back channel contacts have already been made but decline to reveal progress, if any. Taliban members who are keen on mainstream politics fear retribution from others, they say.

Pakistan’s strategic ambition in Afghanistan directly undercuts India’s stake. It has withstood US pressure to curb the Haqqani network, which is believed to be behind several assassinations and suicide attacks in Afghanistan. Most analysts and government officials Forbes India spoke to in Kabul believe that Pakistan’s ISI is directly involved in these attacks, including the assassination of chairman of the High Peace Council Burhanuddin Rabbani in September.

A Wall Street Journal report, quoting senior Obama administration officials, says that the US is looking to speed up its exit from Afghanistan by moving to an ‘advise and assist’ role. A strategic agreement between the two countries is already under negotiation. Moving to an advisory role could mean faster military withdrawal and more dependence on Afghans for security. That will also be Pakistan’s chance to increase influence. However, conciliatory gestures such as giving India the most-favoured-nation status indicate that it may be concerned about its own economy that could benefit from regional co-operation. Given domestic pressures on European nations as well US administration for economic austerity, dollar flows to countries like Afghanistan and Pakistan could dwindle. The Pakistan government and the army are well aware of it and that could lead to a more sensitive policy towards Afghanistan. But that is only tenuous speculation.

The solution which seems to have a consensus is a federal republic. More autonomy to different regions will help locals decide their priorities and reduce resentment of ethnic groups such as the Hazaras and Tajiks that feel politically outmanoeuvred by the numerically superior Pashtuns.

The US-led international community is still focussing on reconciliation. While the Pashtuns are pro-reconciliation, the non-Pashtuns are largely against it. Abdullah Abdullah says, “The most, most, most compromise that we, the non-Taliban can do, is that the Taliban can continue to fight for their Islamic Emirate but not through violence.” Abdullah says that they should fight politically. But the moment they give up the idea of Islamic Emirate through Jihad, they lose their identity. They become merely conservative Muslims. “No one has taken into account that existential reality,” Abdullah says, hinting that a reconciliation is near impossible.

Afghanistan’s domestic politics will also hinge on how Pashtun tribal relations shape up. “In Kandahar 80 percent of official posts are with one tribe,” says Mahammod Khan of a rival to his Alokzai tribe. The Pashtuns form about 42 percent of Afghanistan’s population. It is difficult to imagine a non-Pashtun president for years to come. That means federalism may be the only viable option to keep the country together.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)