Women need to be at the front and centre of Covid-19 recovery: Mitali Nikore

The founder of Nikore Associates, a youth-led economics research think tank writes about how women have consistently been left out of India's growth story, and why changing that will make all the difference

A multi-stakeholder approach is required for increasing women’s participation in the workforce

A multi-stakeholder approach is required for increasing women’s participation in the workforce

Image: Shutterstock

The recent release of the fifth round of data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) has been accompanied by a singular focus on one particular statistic—the increase in the total sex ratio from 991 to 1,020 women per 1,000 men. This one statistic led to a misleading inference that there are now more women than men in India. There was collective amnesia about the fact that this statistic was an estimate based on a survey of about 6.4 lakh households, representing 0.2 percent of India’s 300 million (3 crore) households, and a conclusion on the absolute number of women exceeding men in a country as vast and gender-unequal as India, should only be based on the findings of a comprehensive national census.

The recent release of the fifth round of data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) has been accompanied by a singular focus on one particular statistic—the increase in the total sex ratio from 991 to 1,020 women per 1,000 men. This one statistic led to a misleading inference that there are now more women than men in India. There was collective amnesia about the fact that this statistic was an estimate based on a survey of about 6.4 lakh households, representing 0.2 percent of India’s 300 million (3 crore) households, and a conclusion on the absolute number of women exceeding men in a country as vast and gender-unequal as India, should only be based on the findings of a comprehensive national census.

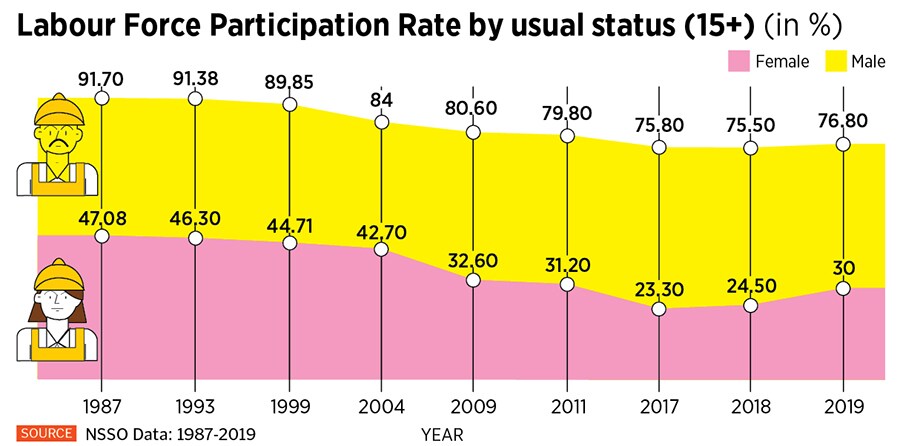

At this time, therefore, it becomes pertinent to reexamine available evidence, and remind ourselves of the persistent gender-based discrimination that limits women’s choices about their lives and livelihoods, and their economic participation.

Different stages of discrimination

First, confirming that discrimination against the girl child begins at birth, there is strong evidence for continued prevalence of the preference for sons. The sex ratio at birth (SRB) has only increased by about 1.6 percent over the last 15 years, between 2005-06 and 2019-21. While at the national level, the SRB has increased from 919 (2015-16) to 929 (2019-21), it has actually declined in 13 states and Union Territories, including some of the most populous states such as Maharashtra, Bihar, Jharkhand, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Kerala.Second, this gender-based discrimination permeates into girls’ education and training, creating barriers to women’s entry into the workforce. Gender gaps in primary and secondary enrolment have narrowed considerably over the past few decades. The gender parity index crossed 1 (indicating parity between girls and boys) for primary enrolment by 2007, and for secondary enrolment by 2011, according to World Bank data.