Heart of Darkness

Forbes India's Neelima Mahajan-Bansal grew up during the trying times of Ugandan civil war. Here, she recounts her family's experience

Uganda was a country straight out of the movies — amazingly beautiful, moderate climate and calm. The tranquility was disturbed when a military coup staged by Idi Amin in 1971 to upstage President Milton Obote was successful. African countries have always been plagued by political instability, this was no different.

There were no immediate repercussions; the country seemed to have settled into a rhythm. Amin traversed the country giving speeches and garnering support of the people, and he visited Kapchorwa as well. My father, a district medical officer, lived in Kapchorwa then. He was amongst those who welcomed him. Amin’s charming oratory skills calmed the citizens of Uganda.

But the peace and quiet didn’t last for long. After systematically getting rid of Obote’s supporters, Amin trained his guns on Asians, the vast majority of whom were Gujaratis. Their crime? They had created highly successful enterprises in Uganda, virtually controlling most of the country’s trade and manufacturing sectors. Amin’s resentment towards the affluent Asian businessman was evident. In 1972, 80,000 Ugandan Asians were asked to leave — and left — the country.

My family moved to the capital, Kampala in 1976 where my dad was posted at Mulago Hospital, Uganda’s largest hospital. My mother, who had came to Uganda in 1975, was working as a lecturer in Makerere University, Uganda’s only university back then. Our family was never asked to leave because the two things that Uganda really needed were doctors and teachers.

Things started to change, a food shortage hit the country as private investors fled. Salt and sugar were in short supply. Milk was scarce. My brother and I grew up on a Swedish milk powder called Meadow Milk Powder. Expats and diplomats could sometimes get a fixed quota of these essential food items from duty free stores. Typically of a crisis, people hoarded necessities and used them sparingly. The petrol pumps were dry, though the doctors at Mulago received a special quota each week. Life was becoming difficult.

Kampala was increasingly becoming unsafe. Those who Amin perceived as threats or took a dislike for would vanish mysteriously. Looting — more often than not by the military — was rampant. We, however, lived cocooned in our relatively safe Makerere University campus apartments.

There were jarring incidents that would increase our sense of insecurity — like the infamous Air France hijack at Entebbe Airport in 1976 where 105 Israelis and French Jews were held hostage by Arab sympathisers. The Ugandan government due to their pro-Palestine cause supported the hijackers.

Dora Bloch, a 75-year-old Israeli hostage, choked on her meal and was sent to Mulago Hospital where my father worked. The doctors did not discharge her long after she recovered to save her from a massacre they believed would eventually follow. But after the Israelis launched a sensational operation and rescued all the hostages at Entebbe, Amin was furious. He sent his soldiers to Mulago who dragged Bloch out of her hospital bed, dragged her down six storeys, took her into the jungle and killed her. A few doctors and medical staff who were believed to have been giving her refuge went missing and were never heard of again. There was an eerie silence in the hospital the next day when my dad went to work and discovered this had happened the night before.

Escape to Kenya

I was due to be born in April 1979 but somewhere around January-February 1979, civil war broke out in Uganda. The rebel forces (against Amin) had started marching in from Tanzania. They approached Kampala from the south. In March, the rebels were near Kampala and there was a danger of a big attack on the capital.

The Indian High Commissioner asked Indians to leave the country. Most of them left on the March 30th. My family couldn’t leave in a hurry because my mother was pregnant and this was a 400 km drive to Nairobi. They didn’t know where they could go and what could happen.

The Makerere campus, where we lived, had around 30 Indians. On the 31st March, there were just a handful left. Once a sanctuary, the campus suddenly felt unsafe. My parents decided to leave for Kenya on the 31st which was a Sunday.

They had just 80 Kenyan shillings and some traveller’s cheques. My family piled into our Fiat 127 and drove to the High Commissioner’s house. On the way, they were stopped by soldiers but we sped away in fear. All the Indians started their journey towards Kenya in a convoy of 30 cars, trucks and a minibus. The High Commissioner’s car led the way to avert the possibility of lootings and trouble on the way.

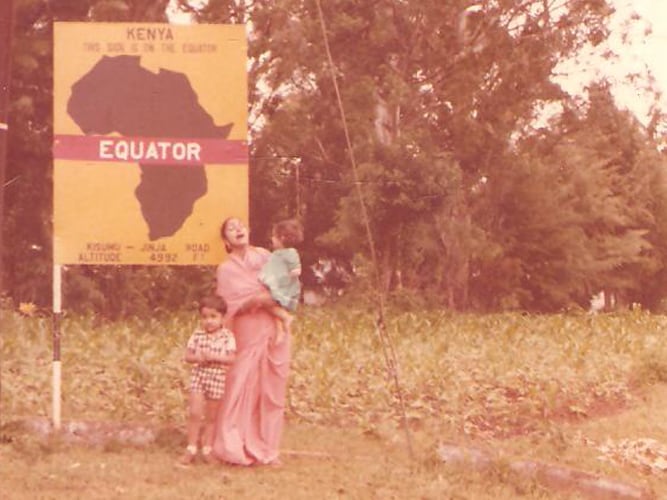

The convoy stopped at Tororo, a small town on the Kenyan border. Indians from Webuye, a neighbouring town had come to receive them. The Birlas were setting up a paper mill in Webuye and had employed several Indians. Among those Indians was our acquaintance, VB Sachdeva, someone my father knew through a medical college friend. He was a chemical engineer in this paper mill. He took them home. The other Indians rested in a guest house and proceeded to Nairobi where they stayed in Gurudwaras, temples and other places that the Indian High Commission in Kenya had arranged for. My parents stayed with the Sachdeva family in Webuye for about 12 days and looked for a good hospital in a neighbouring town called Kisumu. The Kisumu hospital was not equipped to handle emergencies and it was 60 km away from where they stayed.

My family decided to drive to Nairobi which was 200 kilometres away. With borrowed money from the Sachdevas and other Indian friends, we drove the 200 kilometres to Nairobi. They stayed with other family friends in Nairobi and I was born in Aga Khan Hospital.

Return to Uganda

Amin was ousted and fled to Libya. So on May 11, we decided to head back to Kampala. When we crossed the border to Uganda, we were stopped by hardened soldiers. Their intentions were not clear. But my brother, who was three years old then, in his innocence, started conversing with the soldiers in Swahili. The soldiers let us pass without any further questions or checking. It was either my brother’s fluency in Swahili or the Mulago Hospital and Makerere University stickers on the windscreen which enabled us to speed through the checkpoints.

On our arrival back to Kampala, our neighbour, Mr Mugambe, a Physics lecturer, welcomed us back. Mugambe had moved all the things from our house to his to prevent our house from being looted. Most other Asians’ houses had been looted in their absence.

The civil war became a constant feature; on evening walks the sound of gunshots would not disturb us. The immunity to the sounds of violence even triggered a few jokes. A professor from Makerere at the time used to say that it sounded like kernels popping in a popcorn vending machine.

Finally, we had had enough of the insecurity and the economic instability. As it is, by July 1981, there were very few Asian families left in Kampala and it didn’t feel safe to stay on anymore.

My father accepted a position with the Government of Zambia and like migratory birds fleeing the winter we moved on from Uganda. We lived in Zambia for seven peaceful and happy years, but that’s another story.