The Style Evolution of Artists

These painters, known for their mature vocabulary, had tasted success earlier for work in a style that was radically different

A Journey Through Pain

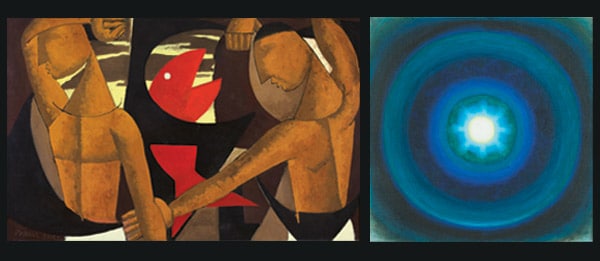

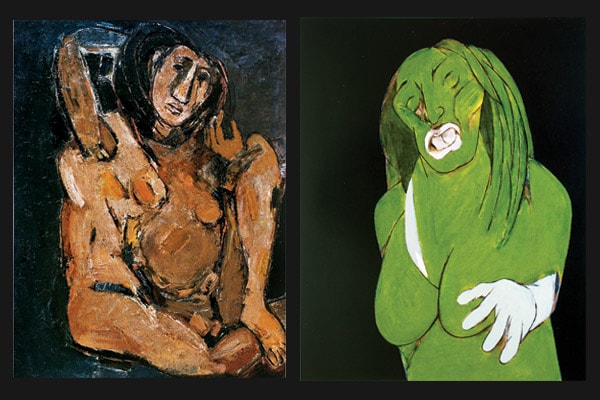

SATISH GUJRAL

b. 1925

Satish Gujral is hearing impaired, yet this has little bearing on his art, for which he trained in Lahore and Bombay. His early work resonates with a feeling of loss, the result of Partition that sundered the country and created geographical barriers which left emotional scars on the people who bore the physical burden of its violence. This series, one of the rare voices that lent to the country’s visual documentation of Partition’s horror, would continue to be enriched after a trip to Mexico and a meeting with Diego Rivera.

His return to India after a stint in America saw Gujral’s work change in more ways than one. Though he remained experimental, the palette became more decorative, the context more affirmative. It was as if he was struggling to project a voice that was celebratory, moving beyond the negative to ideas that found a resonance in what might be considered hopeful. Musicians, dancers, jugglers, athletes: These were components that defined his painterly universe, resulting in his popularity in a society that no longer had space on its walls for laments of despair.

Towards a Transcendental Future

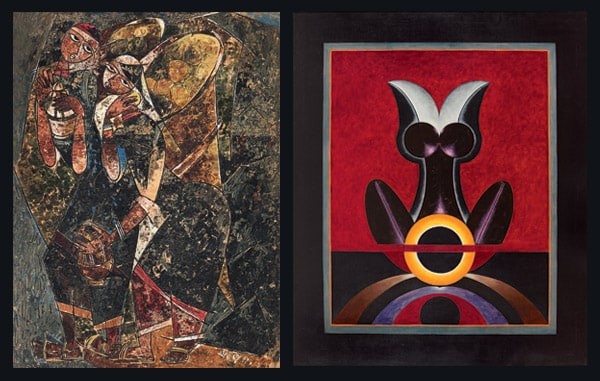

BIREN DE

1926-2011

Despite his early grooming in Calcutta’s Bengal School movement, a stint in New York would find Biren De drawn to the idea of free space and the ability to knit a narrative, and not be defined by the frame of the canvas. His ability to create a theatrical scene and hold it up for the intimate gaze of the viewer was his particular strength based on drawing his subject close. This would define the temper of high modernism for most practitioners of modern art in the ’50s and ’60s, but in De’s case this was set to change dramatically in the ’70s.

At a time when India was providing momentum to the flower power movement and neo-tantra was getting a fillip, De began to work on his defining style around the idea of energy and transcendence. Though devoid of the symbols of tantra that other artists used more liberally, the idea of a powerful force and a focus on meditation is central to the idea of these paintings with their strong, primary colours.

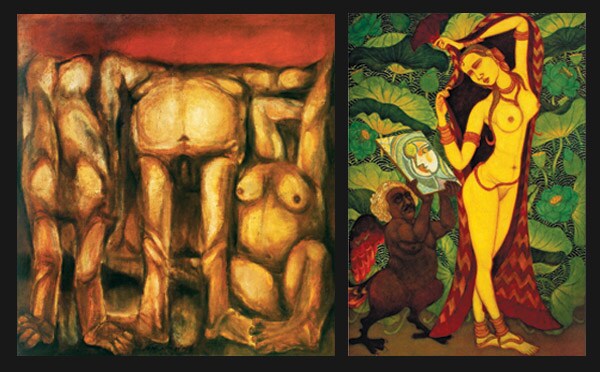

Features Without Form

GR SANTOSH

1929-97

This Kashmiri artist was ahead of his times, taking on his Hindu wife’s name as his own surname to protest their communities’ opposition to the marriage. A landscape painter in Srinagar before becoming a student of NS Bendre in Baroda, under whose guidance he created a rich body of figurative compositions, GR Santosh settled in Delhi and found a reservoir of patronage. Though several Indian artists had been inspired by cubism, in his hands it acquired a lyricism that could only have been borne of the land.

On a visit to Amarnath, he recounts a mystical experience that was to change the direction of his art forever. Taking a few years off to study the role of sufism, Santosh soon developed a visual language of tantric art that was uniquely his. He used the symbols of tantra but abstracted it in the form of a mirror image, locating clues within the field of the painting. This balance of energies was part of the primordial order of nature, and he studied it to develop its evolution into transcendence that is at the root of spiritual awakening. His highly regarded works lay at the cusp of neo-tantra art that was to become popular from the mid-’70s onwards.

Loss and Longing

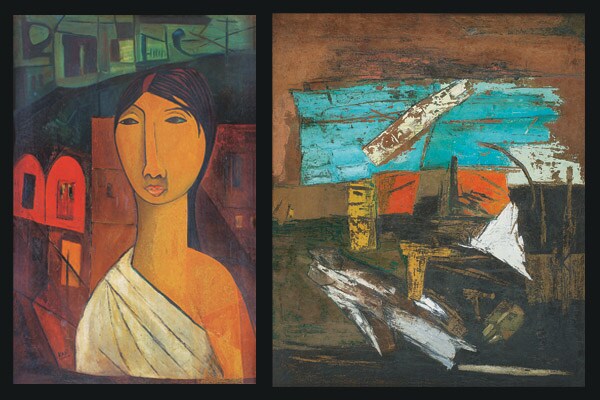

Ram Kumar

b. 1924

A student of economics in India who fraternised with the communist intelligentsia in Paris where he studied art, Ram Kumar’s stint in London resulted in works that featured the homeless. In India, this found expression through his work on the widows of Varanasi. Even during this phase, when his figures were rendered similarly to Modigliani’s, Kumar grappled with himself, drawn to a language that was more abstract than figurative; his initial stint created a riverfront mass of huddled buildings, gateways, arches and paths.

Even though his work was highly regarded, Kumar moved into a language of formless abstract paintings—something that did not enjoy a premium in the market at the time. He continued to paint Varanasi, but it was no longer identifiable, represented by a corpus of colours and a sense of animation and movement. Later, he was drawn to the landscapes of Ladakh, but for most part he devotes his energy to Varanasi, giving India one of her few practitioners of the non-representational that enjoys a critical following.

The Long Route Home

SH RAZA

b. 1922

Among India’s most popular artists and a founder member of the Progressive Artists’ Group in Bombay in 1947, SH Raza began his career as a painter of impressionistic landscapes, something that would characterise his work when he shifted to Paris in 1950. While there, and as a result of a trip to New York, his work developed into a style that came to be known as ‘gestural abstraction’. It consisted of thick impasto applied with a sense of energy that gave it movement, and though he often worked with a dark palette, a sense of his Indian roots was betrayed by the use of vibrant colours as accents.

A third and final career change saw him reach towards his Indian heritage from Paris when he began to work, from 1979 onwards, on a series that would develop into his popular Bindu, Mandala and Germination body of works. They evoked the discipline of meditation and the harmony of the five elements, and were a celebration of colours that had resonated with him ever since his first glimpse of Basohli miniatures. Gradually, thereafter, he moved his oeuvre to this new found vocabulary and has been entirely consumed by it to this day, even if the bulk of that journey was realised in France.

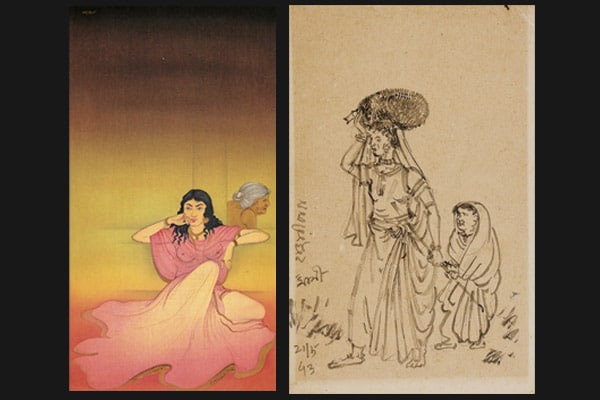

Folk Modernist

JAMINI ROY

1887-1992

No one represents the transition in an artist’s mid-career oeuvre better than Jamini Roy. Trained in the realistic style prevalent in art institutions such as the Government College of Art in Calcutta, and growing up in the midst of the Bengal School at its zenith, his early works are impressionistic, inspired, no doubt, by Monet and Matisse.

But Roy found existing tropes claustrophobic and wanted to create something that was Indian but without the sentimentalism of the Bengal School of art. His inspiration came from the Kalighat pat painters whose bold outlines and simplistic renderings he adopted. His subjects were often the Santhals, musicians and dancers, popular Bengali myths that introduced the parable of the cat and the lobster, and his affinity to Biblical iconography. These folk-like renditions have come to be viewed as India’s earliest tryst with modernism. Wanting to make art accessible to a wider public, Roy created an atelier where his works were copied by disciples and acolytes, resulting in a prolific output.

Loneliness and Fear

TYEB MEHTA

1925-2009

Tyeb Mehta was permanently scarred from witnessing a man being killed during the Partition riots. As a result, he devoted his life to the struggle between individuals for power, without taking a view on the morality of right or wrong. His early works are characterised by the influence of Western modernism, but the strife of the lonely figure remained an indelible part of his work. His expressionistic technique was subject to his perfectionism, and he often destroyed canvases he was unhappy with.

The transition in the ’80s saw his style becoming more minimalistic, paring away all but the essential in flat colour fields. The subject of his articulation was still violence, but the figures were no longer anonymous. Indeed, in many, it was his representation of Kali, the avenging goddess, in a melee with the demon Mahisasura, that exemplified his best works from this period. The represented figure of these protagonists is horrifying—or is it horror that they, in turn, see? The strong outline and the use of only a few colours peels these works down to communicate without artifice.

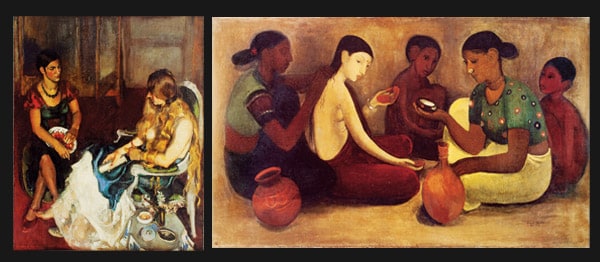

A Bridge Across Continents

AMRITA SHER-GIL

1913-41

Born of a Sikh father and a Hungarian mother, with roots in India and Europe, where she studied at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, Amrita Sher-Gil was flamboyant and impetuous, as passionate about life as about art. In her Paris salon, she painted in the style that was current at the time—studies of young people that lent beauty to their youth and dalliances. Within this enchanted world, she might have prospered but for a visit to India that saddened her sufficiently to return here to create a new language of Indian modernism.

In part, this was a rejection of the Bengal School, and Sher-Gil launched on her career somewhat deliberately. She rejected realism in favour of the Ajanta palette, and evoked the world of miniatures in her flat renditions, although her subjects were chosen from an India she discovered on her travels. A first for Indians, she used models for her paintings, and looked around to spot everyday scenes of life that captured her imagination. She died at 28, but has left her indelible stamp on Indian art in the 20th century.

Student, Artist, Teacher

NANDALAL BOSE

1882-1966

A long with Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose was one of the foremost exponents of the Bengal School style that had its genesis in a ‘national’ idea of art inspired by the Ajanta frescoes and Indian miniature paintings under Tagore. Evolved in the Japanese wash style, its subjects were chosen from Indian mythology and a romanticised past. Elegantly rendered, Bose’s paintings of this period catered to an imagined glory and became a tool of resistance against the colonial power occupying India at the time. Bose’s role as an art teacher further consolidated this idea as a legacy.

It was in his later years in Santiniketan that Bose began to change along with his students Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee, drawn to an expressionistic style and moving away from idyllic notions to the reality of the countryside and its people. It was this transition that would provide the fillip to the genesis of what would develop as modernism as the country grappled to find a painterly language that was its own and not influenced by the West.

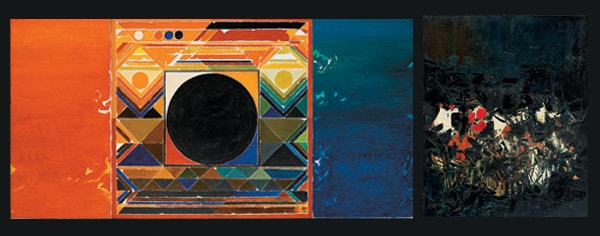

From Form to Formless

VS GAITONDE

1924-2001

V S Gaitonde’s is a parable of posthumous success that re-enacts the popular concept of the struggling artist in a garret who fades away in penury. The tragedy is that he was recognised in his lifetime for the excellence of his work but could not find a market for it. Like most artists, his early works were figurative and drawn to the idea of Nehruvian socialism and the development of a resurgent India.

His works began to change even before a stint in New York, where he was inspired by the colour fields of the artist Mark Rothko. Considered India’s foremost abstract painter, he preferred the term ‘non-objective’ for his non-representational paintings. He developed a style of layering that added depth and luminescence to his canvases, and though they were static in the absence of any form, a zen-like movement nevertheless animates them. Gaitonde’s excellence is only now gaining global recognition and has fetched him record prices and, later this year, a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

From Darkness to Light

A RAMACHANDRAN

b. 1935

A Ramachandran’s was a dark world bereft of optimism in his early years as an artist. He painted scenes that were rampant with grief and violence, macabre scenes of mankind’s depravity. In part, this arose from a communist rejection of beauty in life, but it was also a result of his upbringing in Kerala and the forces that held his imagination hostage.

But the transition couldn’t have been more dramatic. On a visit to the countryside outside Udaipur, in Rajasthan, Ramachandran found himself drawn to a temple beside a lotus pond. Mesmerised by its beauty, as by the tribal women who inhabited the area, the artist found his resistance to what modernists rejected as decorative, melting away. He has been back to that spot scores of times since then, painting the enchanted world of nymphets, dragon flies, water-lilies, often painting himself within the paintings too. Viewed by many as escapism, Ramachandran’s sonnet to loveliness and beauty emerges from the finest tradition of Indian art having the ability to inspire and heal.

(This story appears in the May-June 2014 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)