Drawings are art too

Far from being viewed only as preparatory works, drawings need to be recognised for their medium and genre

Art schools have always been at pains to teach students draughtsmanship as a true measure of their skill. Since the 15th century, from the time of Leonardo da Vinci, artists have filled thousands of pages of sketchbooks to capture the nuances that escape us—the way a finger crooks around another, or a few strokes to suggest the contours of a body or even how a crumpled leaf floats to the earth. Many artists work on their masterpieces, or their more ambitious paintings, after completing a single or a series of drawings to help them gain perspective on the final result, and to correct any anomalies of scale. But drawings are a separate and legitimate part of their oeuvre, complete in and by themselves. For art connoisseurs, these often-neglected examples reflect an artist’s skill and talent.

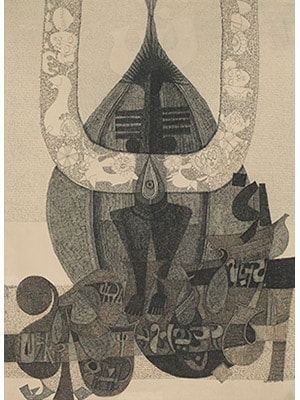

J Sultan Ali (1920-90)

Pen and ink on paper

The Chennai-based painter who had a studio in the artist commune of Cholamandal, en route to Mahabalipuram, was drawn to folk narratives, his vocabulary informed as much by its bas reliefs as by the mythologies of serpents and Shiva that proliferate in the region. The accompanying drawing is replete with these suggestions. Sultan Ali has contrasted depth and shade masterfully to arrive at a narrative that is rich with nuances like Shiva’s third eye and the lingam as stand-ins for the powers vested in the ‘yoni’ or feminine principle of Shakti. He has even linked them through a reference to Nandi as the primal beast, which may have had its origins in Harappa where similar seals have been excavated. The artist has also created an illegible script that runs across the bottom of the drawing in a reflection of continuity with an unknown, distant past. The stories and inferences are engrossing by themselves, but it is the clever hatching and line work in this drawing that makes this piece as powerful as any of his iconic paintings.

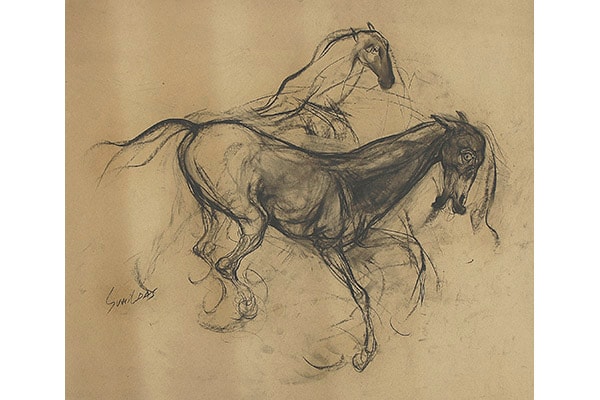

Sunil Das (b. 1939)

Charcoal on paper

The only artist apart from MF Husain who is associated with a profusion of paintings depicting horses is Kolkata’s Sunil Das, who established his career following the stallions of the mounted police in the city. The artist has captured their spirit and energy in charcoal renderings that are among the more outstanding equine studies of the previous century. It wasn’t just horses that captured Das’s imagination. On an earlier trip to Spain, he had been equally fascinated by bullfights. The experience fanned his desire to make charcoal drawings of bulls on paper. Das, be it through his bulls or horses, captures their restless temperament in a series of short, flowing lines that seem to arrest them in motion. The testosterone-inducing quality of his horses is steeped in their masculinity; their untameable personality vividly rendered through a suggestion of neighing heads and startled eyes. His distinctive horse drawings have a huge following, causing the artist to revisit them at different points in his career, and thus becoming associated with them.

FN Souza (1924-2002)

Pen and ink on paper

FN Souza had made London his home since the 1950s, but the demons that had haunted him in India chased him all the way to Europe and, eventually, to America. His drawings, whether of heads with distorted limbs or nudes, are rarely pleasant, suggesting a deep-rooted anger. Souza was a genius with graphite pencil or pen. He could instantly turn a piece of paper into a work of art. A critic of the church and the state, he often painted the clergy as damned and damning, and businessmen as corrupt and malfeasant. This 1955 drawing is a slight departure because it paints a city businessman in front of a European skyline. The lines have none of his characteristic virulence, though the man’s face betrays a predatory hawk-like stance. The widespread eyes and jowly angularities are sharp, as though he is searching for a prey. By foregrounding the figure who is looming over the cityscape, he creates a sense of foreboding, a precursor to the nature of his later drawings.

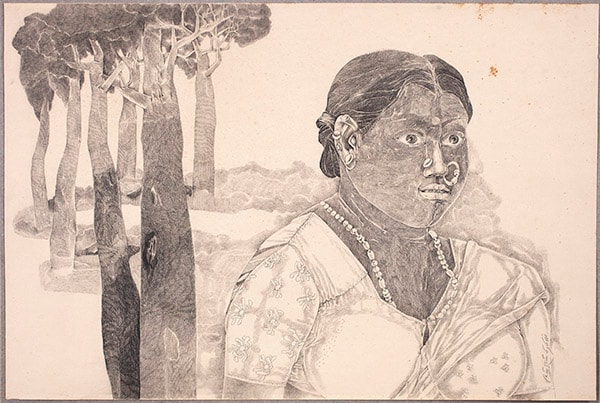

K Laxma Goud (b. 1940)

Graphite on paper

A sensualist, at least when it comes to his art, Laxma Goud is recognised as one of the finest draughtsman of our times, often completing works with a dab of water colour or pastel to add depth and a jewel-like resonance to his drawings. Professionally trained, the auteur turned to his Andhra roots to provide a narrative that combined a tribal vivacity with a rural sensibility and an urban outlook. Merged together, the disparate elements create a distinctive language that contrasts the languor of the countryside with the torrid response of its people, animals and even vegetation. The woman in this drawing could be any one of thousands from his neighbourhood, her full breasts almost bursting from her blouse, her frank gaze and defined lips almost erotic; yet there is nothing out of the ordinary about her. The work alludes to the passions that form the trusses and cords of a society, but escape our attention in the blinding light of the attention-grabbing, tinselly glitz and glamour.

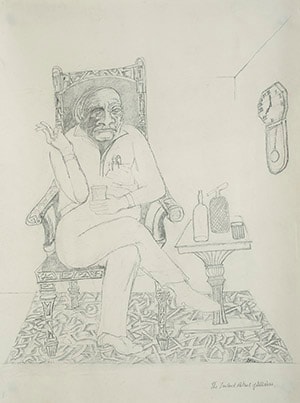

The 7 O’Clock Ritual of Lall Nana, c. 1970s

Krishen Khanna (b. 1925)

Graphite on paper

The London-educated banker might have remained a hobby artist if it wasn’t for Husain who egged a young Krishen Khanna to leave the trappings of the corporate world for a more creative quest. An observer of people around him, he came to be particularly well known for recording the lives of pavement fruit sellers, tea-shop and dhaba customers, and the foibles of those born to class and privilege. This delightful drawing almost caricatures Lall Nana’s activities as soon as the clock strikes 7 in the evening. Grandpa Lall is shown seated in his living room armchair, the mandatory plush carpet under his feet. A side table has all the accoutrements of his evening ritual—a bottle of whisky, a soda maker and a crystal glass. He is formally dressed for the occasion, his crossed legs reveal feet shod in shoes. There is a selection of pens in his shirt pocket, a cigarette dangling insouciantly from the fingers of his right hand. The brooding figure is brilliantly rendered, and just three lines on the upper right hand corner provide depth, both to the room and this drawing.

King Making Confession, 1977

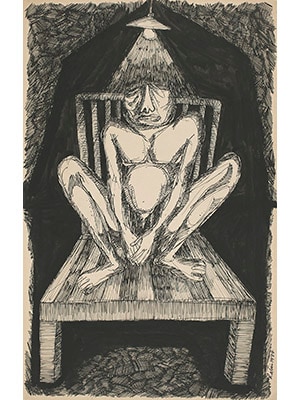

Rabin Mondal (b. 1929)

Brush, pen and ink on paper

The virtuoso primitivism of modernist Rabin Mondal has escaped most serious collectors, but this Kolkata-based artist has been a consistent voice that highlights the moral and political decay of society. Reflecting the bleakness of those who abuse positions of power, he represents high office and wealth as corroding influences that render his protagonists lonely and isolated. He often depicts these authoritarians as naked, therefore weak, as seen here. This drawing, from from one of his most iconic series of ‘King’ paintings, is complete and therefore an unlikely contender as a preparatory work for an oil painting. It portrays the king positioned under a harsh light, the rays forming a dunce-like cap over the confessional figure. In the absence of even a fig leaf to hide behind, the king conceals his nakedness with his hands. Mondal’s powerful use of black, the cross-hatch to represent depth, and the use of white as a negative space serve to dramatise the scene, and one cannot but help feel sympathetic for the melancholic figure who is reduced to an infantile object of ridicule.

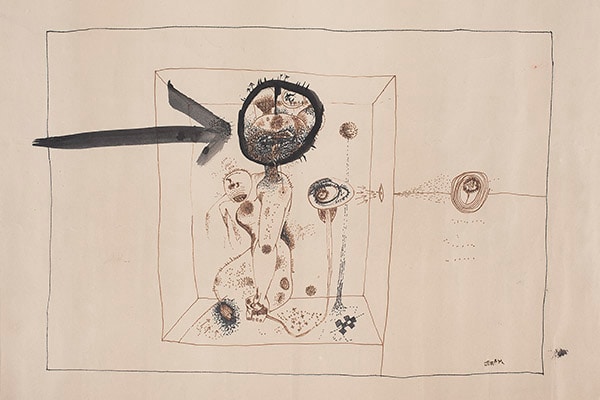

Jeram Patel (b. 1930)

Pen and ink on paper

Space and dimension as a measure of things have been Jeram Patel’s semantic for as long as he has been an artist. The Ahmedabad-based artist rarely involves himself with the pursuit and nuances of narratives from life, choosing instead to concentrate on the more esoteric. Drawn to anthropomorphic forms, he has often worked within the realm of nature, with its weathering and erosion as his chosen metaphor. He did, however, dally briefly with human figures, sometimes disguising or positioning them beside landscapes, the two an indelible part of each other. But his work is not without its use of symbols, especially the ‘tantra’, which is evident here in the way he uses the scientific canon to represent the male and the female—the arrow and the circle—to suggest the concept of fertility and continuity, aspects of life that have absorbed his work. The fine pen lines with and within which the subject has been rendered are not subverted by the dominant brush and ink strokes. They stand their ground by arresting both our eye and imagination.

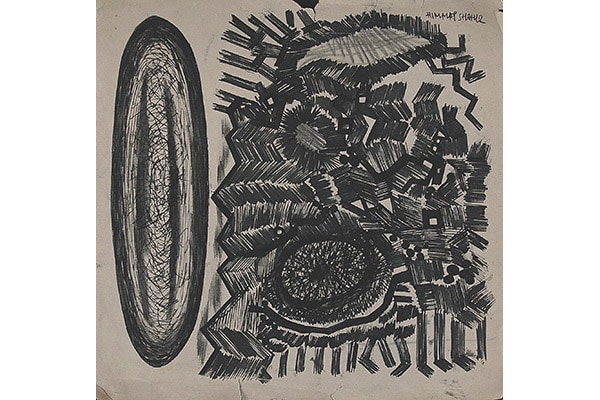

Untitled, 1962

Himmat Shah (b. 1933)

Pen and ink on paper

Growing up in proximity to lothal, the Harappan site in Gujarat where excavations have revealed a lost civilisation, sculptor Himmat Shah has often found himself in those labyrinthine digs, a volunteer mapping the terrestrial world. He was drawn to a growing abstract language that he adopted almost by instinct. He rejected the present, choosing instead a metaphor that is rooted in some ancient regime. His drawings from the ’60s are striking for their confidence, almost as though he was a part of the enactment of the mysteries that time has refused to blur. In the same decade, he also worked on paper collages that he burned slightly to give his works a sense of history. It was never the particularities of people and places that captured his imagination. Instead, he concentrated on the passage of time and the warp that has segued a past and present, and will continue into the future, regardless of our individual histories.

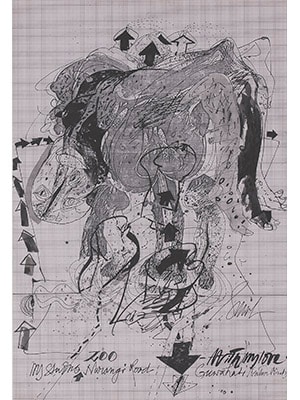

Untitled, 1975

Amitava (b. 1947)

Pen and ink on paper

Among the most significant artists of his generation, Amitava Das is a maestro with pen and pencil, able to make his lines sing—though often, his subjects tend to be dark and not a little threatening. The artist, who minimises the scope of his subject by reducing it to a few articulated lines, leaned towards a more complex, layered field early in his career. The environment and the condition of man are subjects that were close to his heart. He sees mankind as both creator and destroyer, able to survive adverse situations. But there is a grimness to existence in the natural world. Amitava’s comment includes all nature’s creatures, be they animals, birds, trees, rivers or mountains. In bringing them together, he binds them within his universe, even though it threatens to detonate under their combined stress. Yet, he avoids a sense of pervading gloom. The amazing line work here demonstrates his ability to fill up paper while leaving the white space in which a deft but minimal use of contours gives his subject both context as well as dignity.

Untitled, 1997

Ambadas (1922-2012)

Pen and ink on paper

Ambadas Khobragade occupied a space that was relentlessly difficult to read. A quiet, reticent artist who chose the silence of Norway as his home, he was restless when it came to depicting a mosaic of lines that were replete with energy. His abstract works were sometimes livened with figures, as in this instance where a figure seems to be fleeing from another who is wearing a cloak. It’s almost prescient of ominous times to come. But Ambadas was anything if not esoteric, filling this drawing with a landscape that consists of the lost hieroglyphics of some ancient tongue, a warning perhaps of things that we are losing even as we are gaining a little, or an algorithm for our times that only a chosen few have the capability to decipher. Isolated from his homeland but nurtured in another, the artist expressed his demons by reenacting chaos, sublimating it through a clever use of voids and depth, never quite abandoning his lines that seem, almost always, to have escaped from his pencil like a runaway doodle.

Untitled, 1967

MF Husain (1913-2011)

Conte on paper

MF Husain was such a consummate artist that he could work in any medium. Though his paintings garnered the most attention, it was his drawings that remained his strength. He accepted commissions for several series. He avoided detail, and rarely played with dark and void spaces to create depth and perception. Instead, he used his lines expressively to suggest an idea or context, leaving the viewer to imagine the rest or complete the jigsaw. But the sparse lines are replete with multiple narratives, as in this case where a male torso can be interpreted as the trunk of a tree. A burst of leaves and the upraised palm in a benevolent gesture are enough to tell us that the artist is alluding to the Buddha. The twist comes from the female who completes the composition. She’s not quite an Ardhanariswar (a being that combines male and female forms), or a Menaka (celestial nymph), but probably Buddha’s young wife who was abandoned by the prince when he sought enlightenment without considering her emotional state or wellbeing.