Contemporary Indian art on the cusp of change

Understanding and admiring the works of a new generation

Contemporary art arrived in India three decades ago, but it has changed direction since the ’90s, when it found a global voice within a local context. A whole generation of artists has created a body of work that is markedly different from that of previous masters—works that need to be understood as much as they need to be admired.

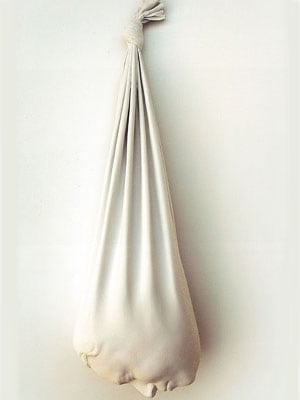

The Burden Of The Body

A Balasubramaniam (b. 1971)

Gravity, 2006

Fibreglass and Acrylic

There could be something gruesome about A Balasubramaniam’s obsession with the body. Despite the wide spread of his art practice, the widely exhibited Bala—painter, sculptor, printmaker, installation artist—is best known for a body of work (pun intended) in which he literally casts himself, moulding fibreglass about his features so they take on his distinctive form. Yet, this preoccupation—the artist choosing to play hide and seek, as it were, with himself—is hardly narcissistic, thereby highlighting that which remains seen, and that which is hidden. In one interesting exhibition, you saw his back disappearing into the wall in one room, the front emerging from another wall in another room. The idea behind this leitmotif is to centre conversations around the body and its relationship with an increasingly material world—based on light, air and shadows—creating a gripping drama through a narrative that could be a fable of our times.

The Dichotomy Of Our Lives

Subodh Gupta (b. 1964)

This Side Is The Other Side, 2001

Bronze, chrome, life-size scooter and milk cans

Arguably India’s most popular contemporary artist for his use of steel kitchen utensils for installations, Subodh Gupta is a master of irony. Like his inspiration, Marcel Duchamp, he uses mass-manufactured products—pots and pans, mostly, but also tiffins—to provoke discussions around the idea of celebration and hunger, aspiration and poverty, the two co-existing in the Indian context. A multi-faceted artist whose painting skills are as astonishing as his gargantuan sculptures, Subodh takes the idea of the everyday to iconicise it—as in this case where the middle-class scooter and the milkpails become a metaphor of urban lives. In his account, the poor and the middle class are often the heroes of their own narratives cast in a nation on the cusp of ambition and nuclear holocaust, instead of concentrating on issues of deprivation and scarcity. Subodh’s body of work is known around the world.

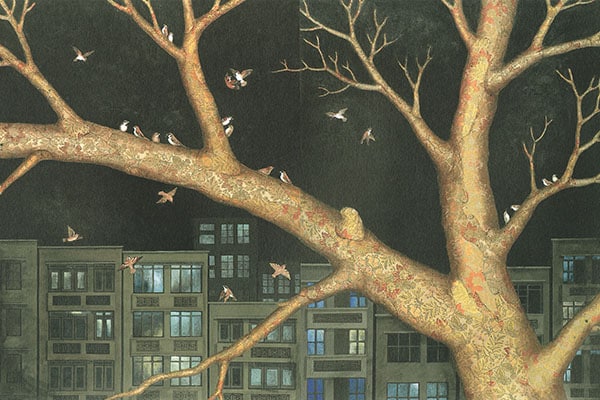

Beyond Ordinary

Jagannath Panda (b. 1970)

Untitled, 2007

Acrylic and fabric on canvas

Jagannath Panda uses a language of such amazing simplicity, it is sometimes easy to ignore the underlying metaphors. The paintings are based on realism. Though devoid of colour, he utilises embellishments to brighten up the everyday through the use of tapestry, fabric, brocade, thread and foil. This canvas reveals little when viewed casually—it is, after all, a cityscape of a darkened skyline. On closer inspection, it spills with portents arising from urbanisation, exoduses and the dislocations of lives. The charcoal sky holds many secrets, prime among which is the absence of human life behind the illuminated windows. Are we strangers in the cities we inhabit? And the sparrows, depicted in profusion, are messengers of those dislocated lives for these are diurnal creatures, not the nocturnal ones as represented by the artist. This deliberate orientation is a pointer to the devices the artist uses to divert our gaze from the seemingly ordinary to the compellingly extraordinary.

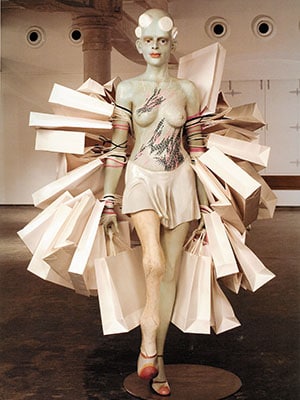

Hybrid Hedonism?

Bharti Kher (b. 1969)

Arione’s Sister, 2006

Mixed media

First glimpses can be misleading. What appears a figure of a fashion model morphs into a hybrid with equine legs (and presumably hooves) on closer viewing. This part-animal, part-human with a tonsured head, which seems straight out of a sci-fi feature, is characterised by the shopping bags that adorn her like wings, creating an almost-mythic creature as an ode to our material world. Bharti Kher, one of the more intellectual among the younger generation of Indian artists, is more associated with the use of bindis in profusion, responding thereby to issues of gender, fertility, inequality and class on one hand, and of anthropological and environmental concerns on the other. That the bindis are also decorative adds an aesthetic layer to this questioning. But in works such as these, the artist steps out of her groove to explore other interesting aspects, the investigation of which results in a visual language of staggering dimension and provocation.

Beyond Time

Pushpamala N (b. 1956)

Hunterwali Sequence from Phantom Lady or Kismet, 1996-98

Gelatin silver print

Trained as a sculptor but known as a photo and visual artist, Pushpamala found her photographic oeuvre in the ’90s, when she began her journey creating mis-en-scenes. A votary of popular culture that informs mass opinions, hers has been a journey of documenting her own self in various mythological or historic representations while playing the central role around a series of iconic images. Among these are spiritual calendar kitsch images, political figures and—as here—filmic characters. The imagining of these figures over time gets re-imagined and re-invented in that particular trope by her, as she re-enacts each familiar scene, allowing herself to be photographed as Lakshmi and Saraswati, or, as here, Hunterwali, the female masked scourge of the underworld from popular ’50s cinema. In giving a fresh lease of life to these seminal characters, Pushpamala extends the longevity of prevalent iconisation through individual enactments and as a personal tribute.

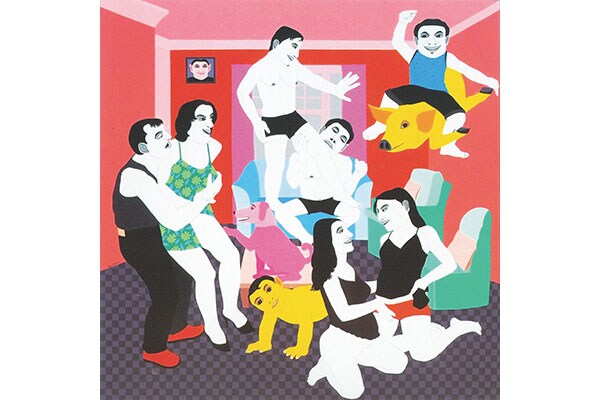

Sexual Transgression

Farhad Hussain (b. 1975)

Body Language, 2008

Acrylic on canvas

Farhad Hussain’s canvases are as full of colour as they are of people within social environments who seem to expend all their energy in having fun. They wear smiles and smirks, laugh openly and with apparent honesty —but are they truly joyful? The settings seethe with incest and sexual deceit, almost as though the artist is pointing to the artifice in our lifestyles. This exploration of interpersonal relationships within mostly interior spaces—and sometimes in city parks—is a bold imagination of the tensions that run between people, whether friends or families. The illustrated figures seem languid but there is between them an unease, even though their bodies appear to be responding to suggestions of suspicious intimacy. The artist’s satirical hint is at something more dark beyond the lightness of colour, of malice and incitement that is intended. An undercurrent of sexuality marks each work when every movement or relationship appears one of seduction and the power of sex.

Distorted Lives

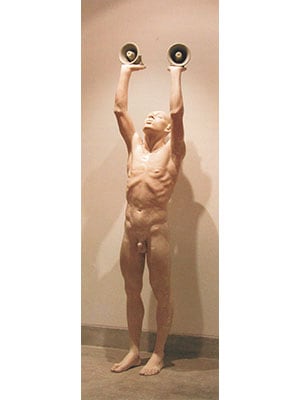

GR Iranna (b. 1970)

Silence Please, 2005

Fibreglass and metal

The human figure has been central to GR Iranna’s work, as a sculptor and installation artist moved to create voluminous works around the world’s desecration and human pain, torment and struggle. Drawn to images of human suffering and misery against a panorama of death and destruction, his commentary can range from wars around the world to the humiliation of soldiers at Guantanamo Bay with equal aplomb. A commentator on the human circumstance, his metaphors have a global voice and reach, cutting across known geographies, thereby transcending time and space. The nakedness of his human figures is deliberate, as it erases any identity so that every man becomes the victim of global politics on the one hand, or of social discord on the other. In the neighbourhood, it can take the form of urban chaos or—as in this case—noise pollution, something that can bring with it attendant health risks that need urgent ministration.

A Chronicler Of Lives

Atul Dodiya (b. 1959)

The Post-dated Cheque, 1998

Watercolour on paper

Atul Dodiya, best known for using his garage shutters to create a narrative in which the social and spiritual mask of Indian society is shown to reveal its inherent hypocrisies, wields the dichotomy of duality as a lethal weapon.

A painter of great skill, he has often also used Gandhi as a motif for his interpretation of social ills. The figure of Gandhi has been used and misused in a post-independent India as people and corporations act out their selfish interests, something Atul reinforces with acerbic wit and scathing humour. The use of historic references—and personages—adds to his metier. A chronicler of social change, Atul has been at the forefront of drawing a narrative for India that distinguishes the selfless from the self-centred, creating a dialogue that significantly discourses the cataclysms of our history across a displaced timeline.

Guilt And The Voyeur

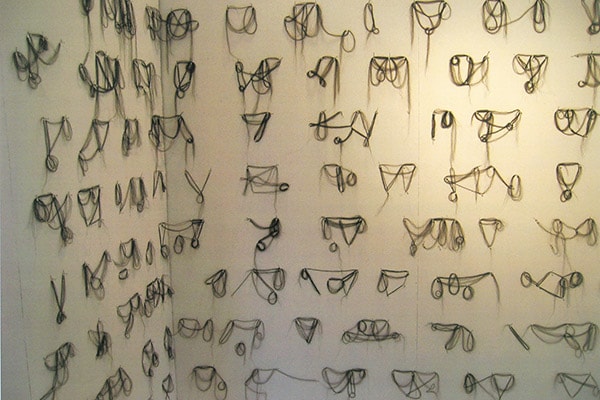

Mithu Sen (b. 1971)

No Star, No Land, No World, No

Commitment, 2004

Thread and nail on walls

Mithu Sen is a watercolourist who uses pigments delicately, but her subject is often the result of a remarkable imagination. She subverts the popular notion of sexuality and femininity—and also masculinity—by confronting it head on and processing it as art. Conflating forms float, whether mere objects, or human and animal body parts and limbs. Look closely at these seemingly ephemeral castings and you could be shocked to discover in them suggestions of genitalia—penises and vaginas—of the excesses of an S&M boudoir. Here, she layers the relationships that pass through the night, laid in nothing more concrete than hasty couplings and as hasty detachments. Her wonderful sense of humour and joie d’ vivre cuts a passage through this commentary of fractured lives and lost loves. Mithu Sen is nothing if not realistic —something her fragile art belies.

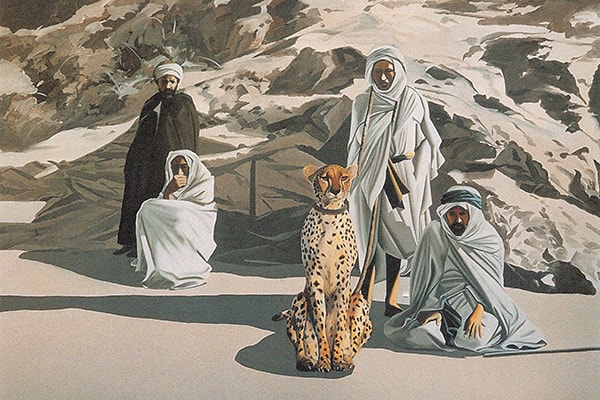

Reflected Unreality

Shibu Natesan (b. 1966)

Existence of Instinct-2, 2004

Oil on canvas

Shibu Natesan is known for the heightened photo-realism of his work, paintings with an almost surreal sense of awareness that makes itself manifest in his amazing canvases. Drawn to subjects that deal with feudalism and patriarchy, he often uses elements of archaeology, landscape and nature, portraiture and animals, to develop his themes. A sense of power and its authority becomes the mover of his template. The context could thus be historic or contemporary—the cheetah in this painting, a recurring motif in his work, has been used with a sports car, for instance, with extraordinary effect. Yet, there is more to these paintings than just the superficial interpretation of the subject. This altered elucidation lies at the heart of his work as he questions the hand of influence, its unseen representation becoming a stand-in for the invisible hand of power. The impact of his paintings is often dramatic, but the veiled reference has even more effect.

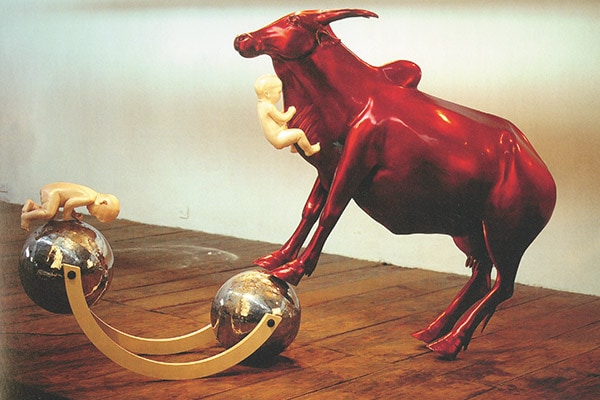

Transient Memories

Sudarshan Shetty (b. 1961)

Home, 1998

Fibreglass and wood

Sudarshan Shetty’s name became familiar to Mumbaikars when his Flying Bus docked on to a city road, resulting in one of the largest works of art on public display in the city. But Shetty has been known for his large sculptural installations around the world, infusing scenes of everyday domesticity with new meaning and life to the point of fetishising middle-class being. Together with simple mechanical objects and forms, he uses repetitive movements to such an extent that they become commonplace, obliterating the aspect of novelty, raking up issues of transience and mortality. The play of the cow as a holy object as well as an idea for giving of herself (think of the Kamdhenu in Indian mythology), the nurturing of children, and the mechanical rocker balanced on two globes creates an unexpected work of art infused with meanings that go far beyond the bucolic simplicity of the sculptured scene.

(This story appears in the Sept-Oct 2014 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)