At the revamped Taj Mahal New Delhi, a younger interpretation of luxe

Post a refurbishment that has taken around three years and over Rs 200 crore, the iconic hotel's restaurants, rooms and the coveted private members club Chambers have all been 'reimagined' to fit new definitions of luxury for the Gen Z and millennial affluent

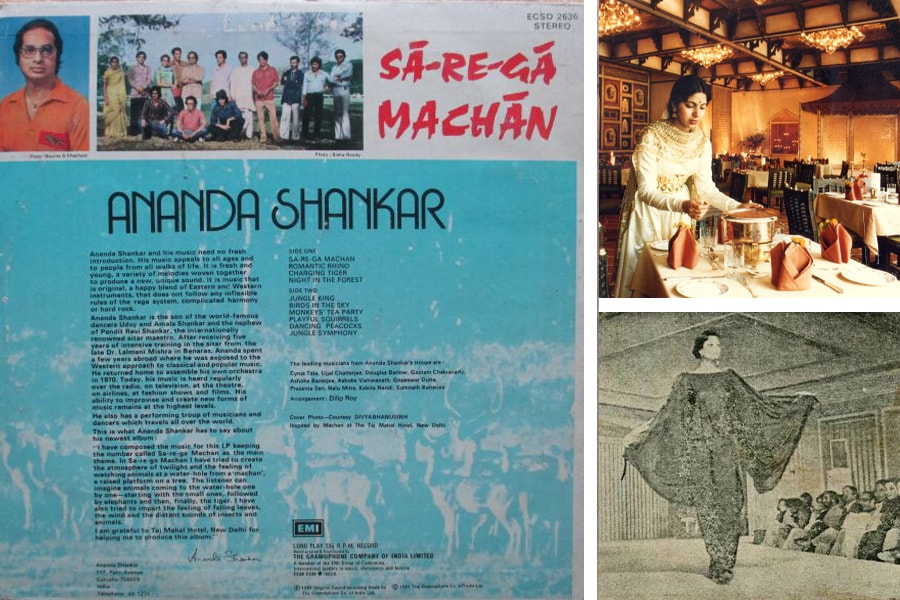

Master bedroom of The Maharaja Suite (above) and Captain's Cellar, the wine bar at the newly refurbished Taj Mahal hotel on Mansingh Road in New Delhi.

Master bedroom of The Maharaja Suite (above) and Captain's Cellar, the wine bar at the newly refurbished Taj Mahal hotel on Mansingh Road in New Delhi.

When the Taj Mahal New Delhi opened on an autumnal Dussehra day in 1978, ‘New Delhi’ was as yet a sluggish town of new money; a political capital but not yet the cultural, social, gastronomic capital of today. The Emergency was just over, a Morarji Desai-led Janta government was in power, and Coca Cola had just quit the Indian market after a change in policy.

It was against this backdrop that the new Taj at 1 Mansingh Road (it would be dubbed ‘Taj Mansingh’ in perpetuity) — just the second hotel to be opened by the Tatas, after the Gateway of India icon they built in 1903 — decided to bring in a dash of sartorial style and glamour. A Yves Saint Laurent fashion show kicked off its events calendar, highly unusual for the times. ‘Lifestyle’ had met Delhi. The rest, as they say, is history.

It’s been 45 years for one of Delhi’s—and India’s—most iconic hotels. But the Taj Mahal New Delhi is not doddering into its middle years. Instead, it is relaunching this weekend with a bang—post a refurbishment that has taken around 3 years and over Rs 200 crore.

Its legendary restaurants, rooms and the coveted private members club Chambers have all been “reimagined” to fit new definitions of luxury for the Gen Z and millennial affluent; the start-up mavericks, creative entrepreneurs and new movers and shakers that make up ‘society’ now.

But there’s dollops of nostalgia nevertheless: The story of the hotel is entwined with the story of India’s capital.