- Home

- Life

- Life

- A Bittersweet Independence: How an economic enterprise took over India and a political coalition claimed it back after 200 years

A Bittersweet Independence: How an economic enterprise took over India and a political coalition claimed it back after 200 years

Overwhelming even the long trajectory of the oppressive British Raj, the cementing of a communal divide which was the tragic legacy of Partition, continues to wrathfully shadow an independent India, a bittersweet dream that haunts the waking hours of the progressive Indian

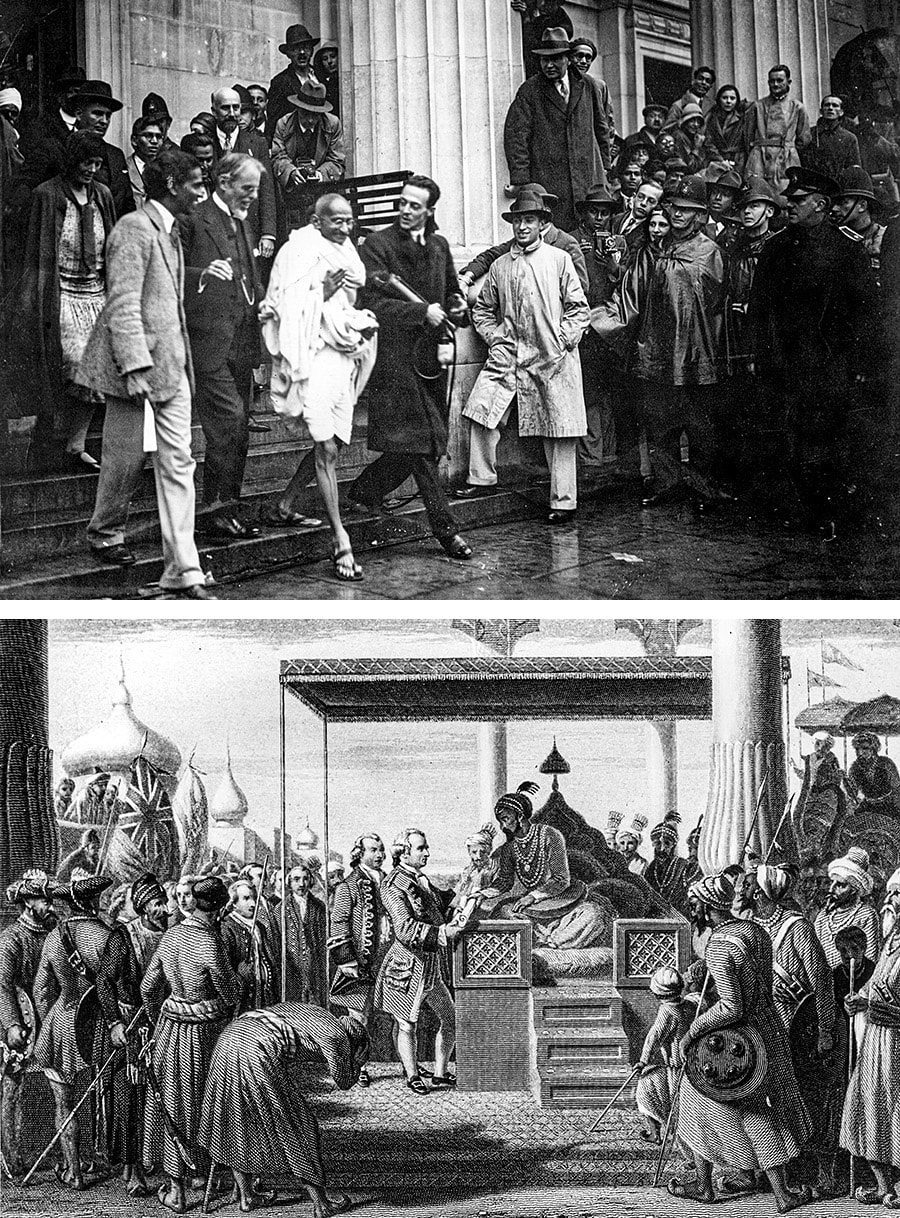

(Above) Indian Congress Leader Mahatma Gandhi leaves the Friends’ Meeting House in London after attending the Round Table Conference on Indian constitutional reform in 1931. (Below)

The defeated Mughal Emperor Shah Alam hands over ‘diwani’ to Governor Robert Clive, thus transferring the tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company in 1758. Image: Douglas Miller/Getty Images; Hulton Archive/Getty Images

(Above) Indian Congress Leader Mahatma Gandhi leaves the Friends’ Meeting House in London after attending the Round Table Conference on Indian constitutional reform in 1931. (Below)

The defeated Mughal Emperor Shah Alam hands over ‘diwani’ to Governor Robert Clive, thus transferring the tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company in 1758. Image: Douglas Miller/Getty Images; Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The East India Company (EIC) was a small enterprise run by a group of London merchants, which had been granted a royal charter in 1600. The charter conferred them with monopoly privileges for 15 years on all trade with the East Indies (the whole of Asia and the Pacific). The group set up a joint-stock company that could issue tradable shares on the open market to investors to attract capital. An administration consisting of 24 elected directors, answerable to the shareholders, oversaw their operations through councils based at their settlements in Asia, who ran the factories.

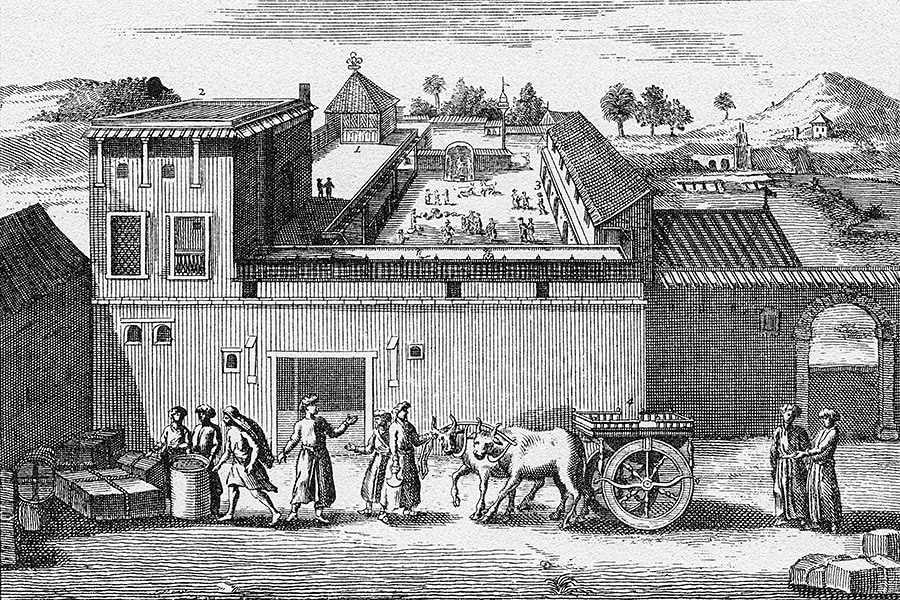

The trading post established by the British East India Company at Surat, India, circa 1680. Universal History Archive/Getty Images

The trading post established by the British East India Company at Surat, India, circa 1680. Universal History Archive/Getty Images

The Company’s ships first arrived in India at the port of Surat in 1608, and gained the right to set up a factory as traders in spices, a primary commodity in Europe back then as it was used to preserve meat. They also traded in silk, cotton, indigo dye, tea and opium.

By the next century, the Company went from being a commercial enterprise to establishing military supremacy; it wrested control of the province of Bengal in 1757, defeating the Nawab at the Battle of Plassey. In August 1758, the Company’s troops led by Robert Clive defeated the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam and forced him to grant EIC the ‘diwani’, which transferred tax collecting rights in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the EIC. It was thus that, within a few years, a trading enterprise had transformed into a ruling colonial power, aided by 250 company clerks and a military force of 20,000 locally recruited Indian soldiers. Answerable only to its stakeholders, the Company looted Bengal and transferred all of its wealth westwards.

A high-ranking English official dwarfs over natives in a procession circa 1754. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images

A high-ranking English official dwarfs over natives in a procession circa 1754. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images

By 1803, the Company, with an army that had now grown to 2,60,000 men, had seized control of almost all of India and was now governed by a bunch of directors from a boardroom in London.

However, 1772 proved to be a disastrous year for the Company. Bengal was devastated by war, and the famine of 1769-70 caused massive shortfalls in expected land revenues. While the British economy spun into recession, the company’s chairman, Sir George Colebrooke, made feverish speculations on its stock that left EIC with debts and led to a run on the banks.

The British government alerted to mismanagement and corruption, stepped in to bail out the company. It passed a bill called the Regulating Act of 1773 that gave it authoritative control over the affairs of the company and placed India under the dictatorial rule of Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General.

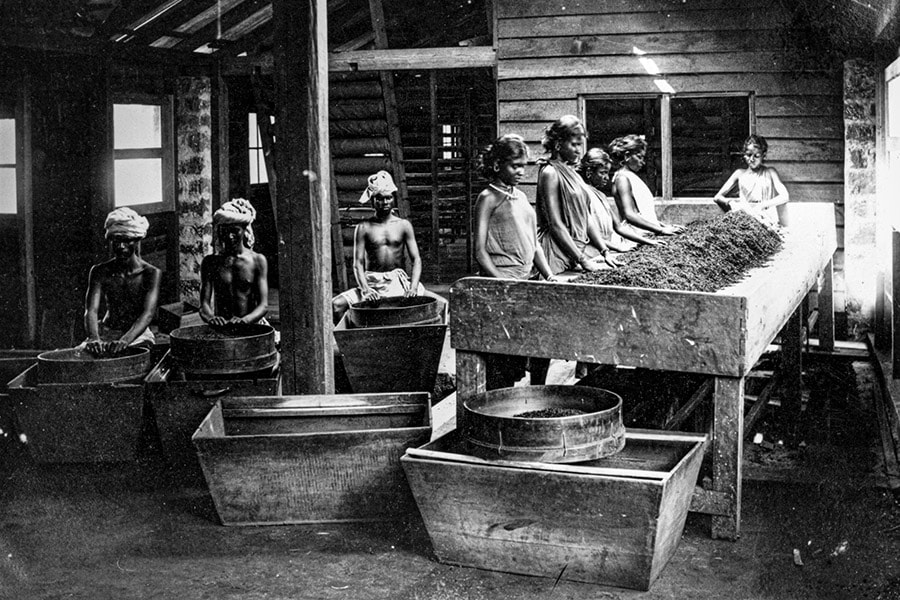

Workers at a tea factory in India. EIC traded in tea and spices, among other goods. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Workers at a tea factory in India. EIC traded in tea and spices, among other goods. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

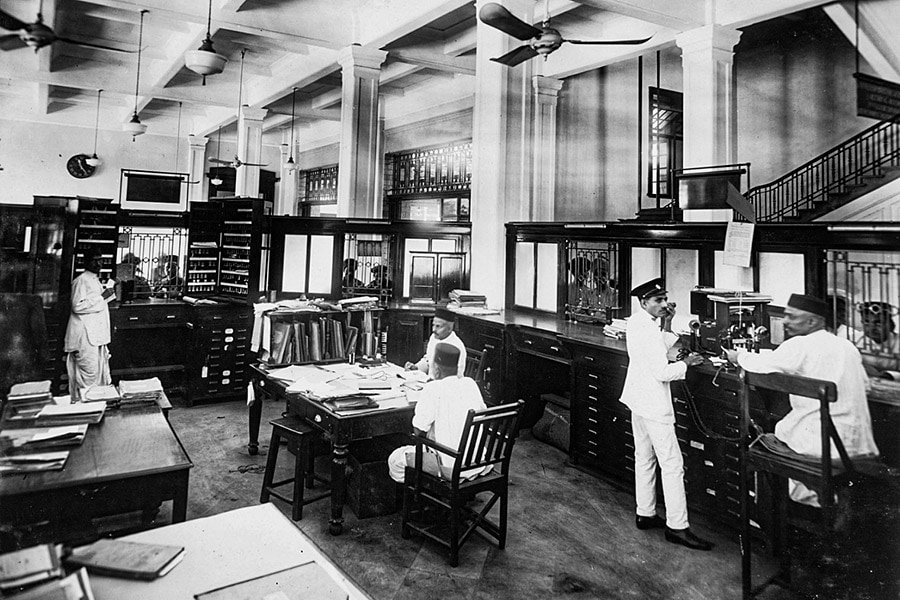

As its commercial monopoly was gradually scaled down, the Company’s imperial ambitions widened. The Company’s army went to war and conquered Tipu Sultan, the Marathas and the Sikhs, annexing native states and establishing their dominion over the entire India. The British introduced a unified system of administration through all the regions and built a network of roads, railways, post and telegraph systems in the country. A Western educational system was instituted in India with the sole aim of creating a class of educated Indians who could serve their colonial masters in the administration of the ‘natives’. Indians found it almost impossible, however, to obtain positions in the Indian administration commensurate with their education and qualifications. In the words of one Viceroy, of the ‘essential and insurmountable distinctions of race qualities’, most British officials did not regard the educated Indian as a suitable material for the more senior positions within the civil service. With so few gaining admission, the majority of English-educated Indians turned instead to law and teaching or politics and journalism or sometimes a combination.

Indian clerical staff at the booking hall of the Victoria Terminus, Bombay, a terminus for the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which by 1870 stretched all the way across India to Calcutta. Image: SSPL/Getty Images

Indian clerical staff at the booking hall of the Victoria Terminus, Bombay, a terminus for the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which by 1870 stretched all the way across India to Calcutta. Image: SSPL/Getty Images

Surendranath Banerjee passed the civil service examination in 1869 but was dismissed in 1874. He turned to teaching, journalism and politics, became editor of The Bengalee and founded the Indian Association at Calcutta in 1876. The Indian Association was designed to stimulate public opinion in India on political questions and to unite Indians around a common political programme. It was the most important of a number of new political organisations being established in the Presidencies of Bengal, Bombay and Madras that were more representative of the newly educated middle classes. In 1877 Banerjee embarked on a nationwide tour, made possible by the development of railways and the continued spread of English as a common language, to gather support for the Indian Association’s political programme of an increased age limit for the civil service examination and increased Indian representation on the legislative councils.

Ironically, the education system created a class of Indians who became exposed to the liberal and radical thoughts of European writers who expounded liberty, equality, democracy and rationality. A common language—English—united this class of Indians from various regions and religions. Alongside the revival of vernacular languages, socio-religious reform movements led by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Jyotiba Phule, among others, sought to remove superstition and societal evils prevalent then and spread ideas of liberty and rational thought, women empowerment and unity among the people. This period also saw the rise and growth of the modern press both in English and in regional languages.

EIC’s own sepoys rose up in anger and resentment against their British employers in Meerut in 1857. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images

EIC’s own sepoys rose up in anger and resentment against their British employers in Meerut in 1857. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Meanwhile, a simmering discontent was brewing among the ‘natives’, caused by the annexation of native states, exploitative revenue policies that had led to poverty and debt among the Indian peasantry, and racial discrimination by the ‘sahibs’. On May 10, 1857, the Company’s own sepoys rose up in anger and resentment against their employer in Meerut. The rebellion was triggered by the introduction of a rifle whose cartridge had to be bitten off before loading it. The sepoys believed that the cartridge was greased with pig or cow fat, which hurt the Hindu and Muslim sentiments. Their united mutiny began in Meerut and spread to many places in Northern India, including Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, Gwalior and Bihar over nine months.

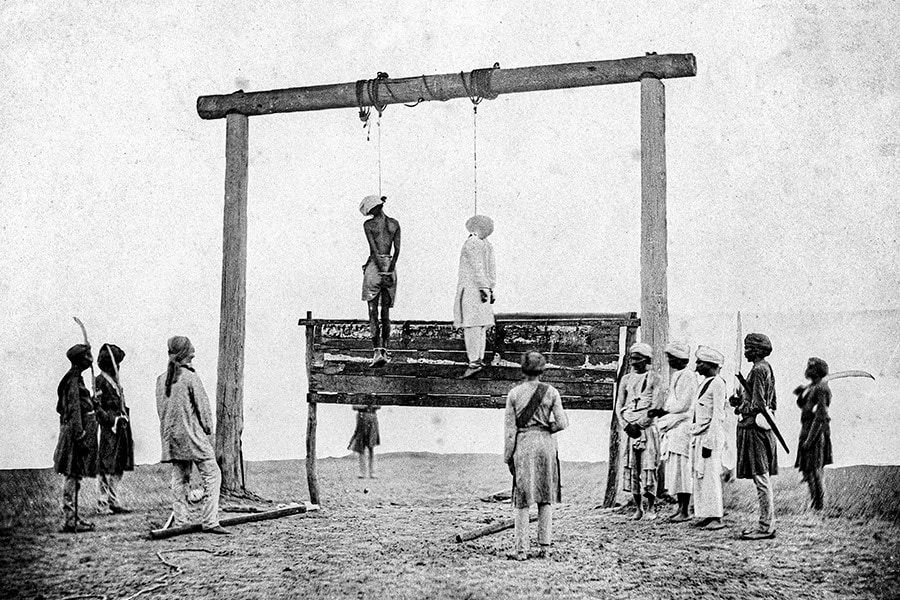

The mutiny was crushed ruthlessly by the British, who killed and hanged thousands of sepoys. Image: Felice Beato/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The mutiny was crushed ruthlessly by the British, who killed and hanged thousands of sepoys. Image: Felice Beato/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The insurgency was crushed ruthlessly by the British, who killed and hanged thousands of rebels, making it the bloodiest episode in the entire history of British colonialism. The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 marked the conscious beginning of India’s fight for independence from the British Empire’s colonial oppression.

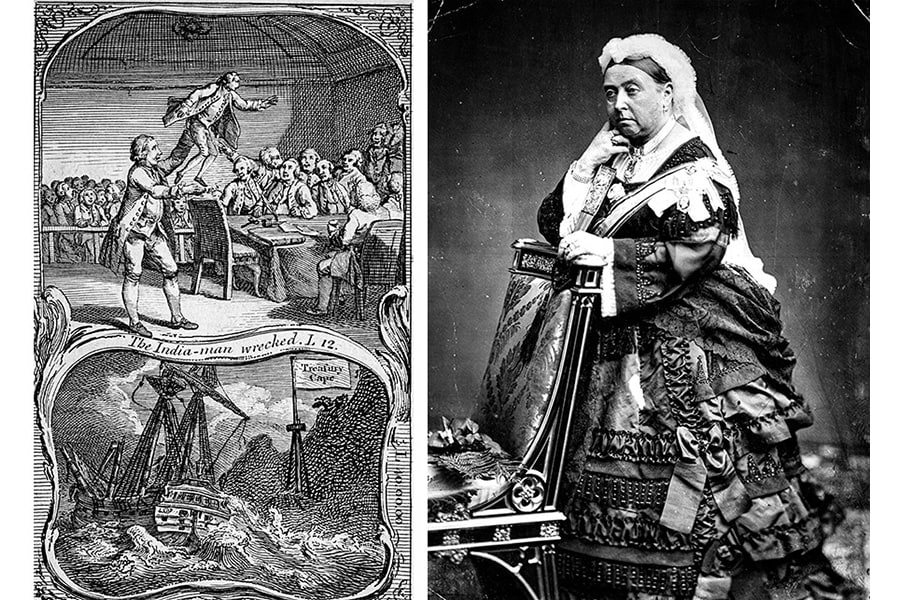

An engraving from 1773 shows Governor Johnstone holding up a distressed Sir George Colebrook by his breeches to the derision of the board of directors and shareholders at the General Court of the EIC; EIC came under the control of the British Crown and Queen Victoria became the ruler of India in 1859. Image: Hoto12/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; Hulton Archive/Getty Images

An engraving from 1773 shows Governor Johnstone holding up a distressed Sir George Colebrook by his breeches to the derision of the board of directors and shareholders at the General Court of the EIC; EIC came under the control of the British Crown and Queen Victoria became the ruler of India in 1859. Image: Hoto12/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1859, it was formally announced that the Company’s Indian possessions would be nationalised and pass into the control of the British Crown. Queen Victoria would henceforth be the ruler of India.

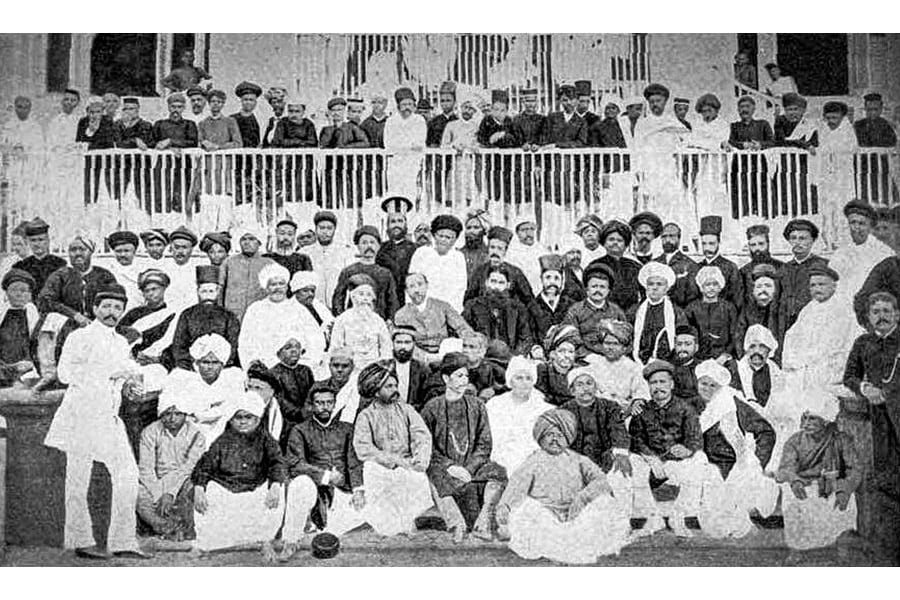

First Indian National Congress meeting in December 1885, attended by representatives from across the Indian continent. Image: History/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

First Indian National Congress meeting in December 1885, attended by representatives from across the Indian continent. Image: History/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

In 1885, Dadabhai Naoroji, Dinshaw Wacha and a group of educated Indians, with the support of Allan Octavian Hume, a retired British civil servant, formed the Indian National Congress (INC) in Bombay. The first meeting, from December 28 to 30, was attended by 72 representatives, over half of whom came from the Bombay Presidency, with smaller numbers attending from Madras, Bengal, the North-Western Provinces and Punjab. INC demanded that legislative councils be introduced in provinces where they did not exist, and more power is given to the legislative councils to make them more representative. It continued to believe that it could influence government policy in India by orchestrating publicity and propaganda campaigns in Britain. In 1889 a British Committee of the Indian National Congress was established in London.

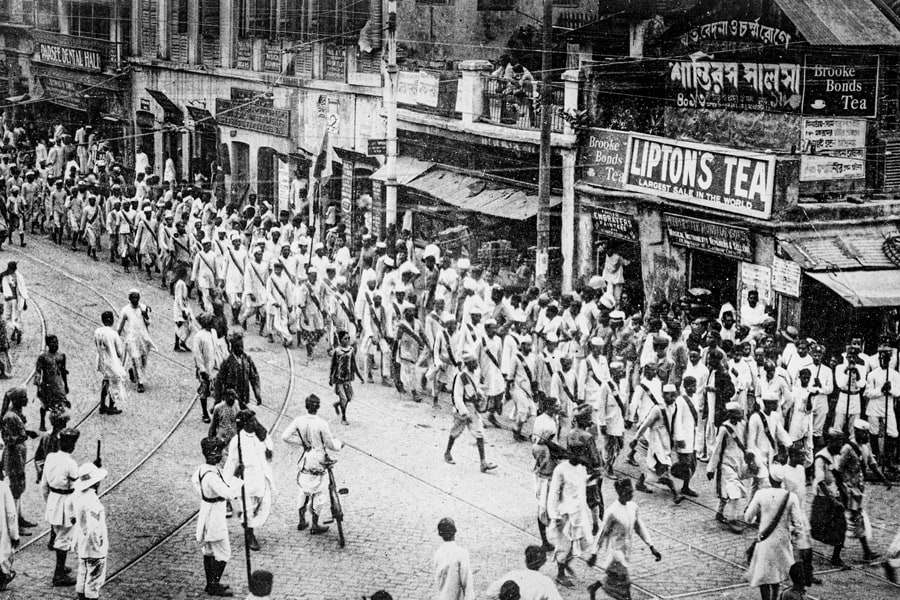

A mass protest against the partition of Bengal in 1905. Image: Bettmann

A mass protest against the partition of Bengal in 1905. Image: Bettmann

In 1903, the British announced their decision to partition Bengal into two provinces, separating the largely Muslim eastern areas of Eastern Bengal and Assam from the largely Hindu western areas of modern West Bengal, Odisha and Bihar. The partition was essentially aimed at debilitating the Bengali nationalists, who were part of the Congress party. While the Muslims were in favour of the partition, as they would have a province they could call their own, Hindus opposed the separation along communal lines. There was widespread political unrest in the Bengal province after Lord Curzon declared the partition in 1905. The English-educated Bengalis regarded this partition as an insult to their motherland. Owing to mass political protests, the partition was annulled in 1911. The 1905 partition of Bengal saw the INC transforming into a mass movement and the emergence of a new ‘Swadeshi’ fervour as Indians started boycotting British goods that had flooded the Indian market.

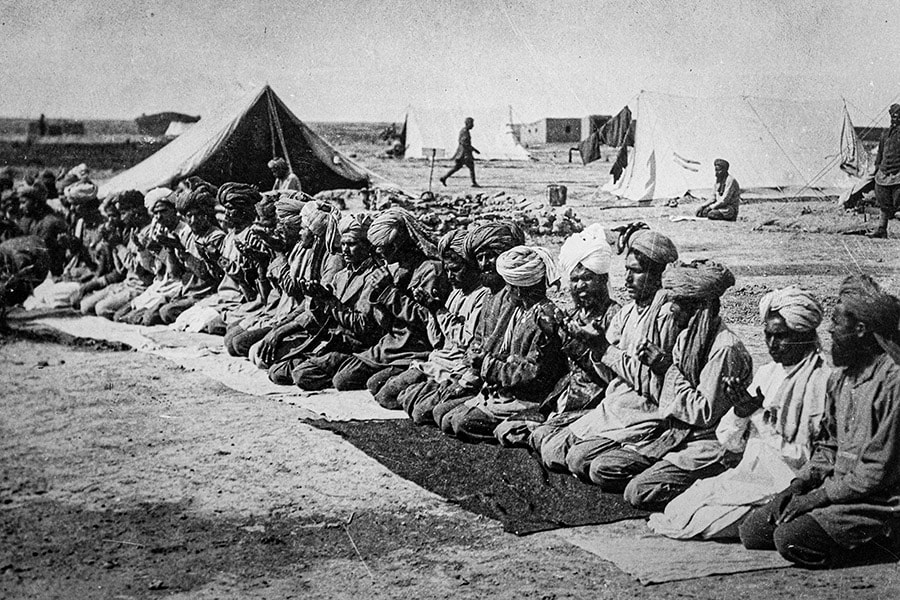

Muslims in British India circa 1906. The Bengal partition gave rise to the Muslim League to protect the interests of Muslims. Image: Bettmann

Muslims in British India circa 1906. The Bengal partition gave rise to the Muslim League to protect the interests of Muslims. Image: Bettmann

The INC-sponsored massive Hindu opposition to the 1905 partition of Bengal had given rise to the need among Muslims for a political representation of Muslims in British India. During the 1906 annual meeting of the All India Muslim Education Conference in Dhaka, the Nawab of Dhaka, Khwaja Salimullah, forwarded a proposal to set aside the self-ban on politics and create a political party that would protect the interests of Muslims in British India, to counter what was then perceived as the growing influence of Hindus under British rule. The motion was unanimously passed, leading to the official formation of the All-India Muslim League.

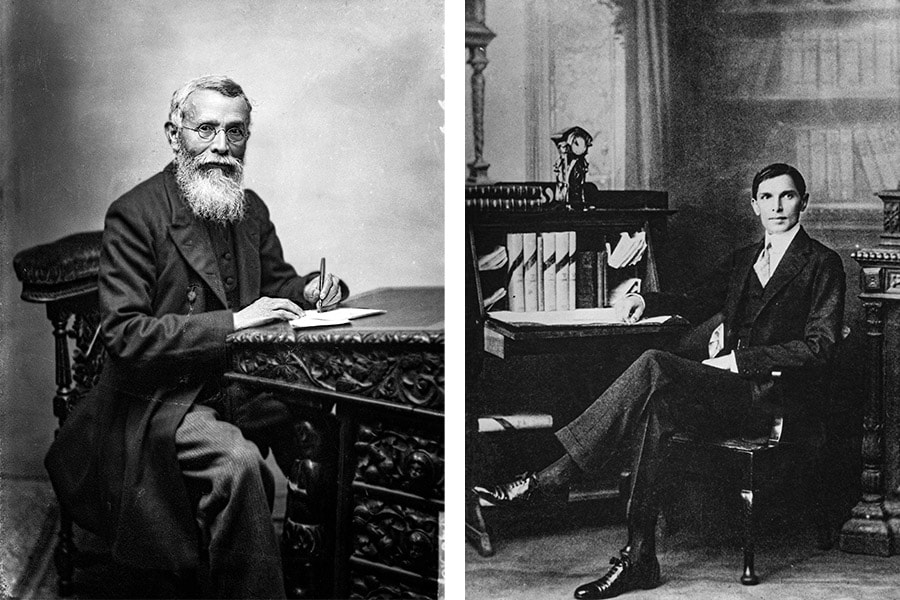

Dadabhai Naoroji, one of the founder members of the Indian National Congress, was a staunch critic of British economic policy in India; It was in England in 1913 that Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a lawyer, joined the Muslim League and advocated self-government for India as its goal. Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Bettmann

Dadabhai Naoroji, one of the founder members of the Indian National Congress, was a staunch critic of British economic policy in India; It was in England in 1913 that Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a lawyer, joined the Muslim League and advocated self-government for India as its goal. Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images; Bettmann

At first, the Muslim league was encouraged by the British and was generally favourable to their rule, but the organisation adopted self-government for India as its goal in 1913. One of its leaders, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a lawyer, advocated Hindu–Muslim unity, helping to shape the 1916 Lucknow Pact between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, which allowed representation of religious minorities in the provincial legislatures. It paved the way for Hindu-Muslim cooperation in the later years.

The formation of the All-India Muslim League in 1906 and the British Indian government’s creation of a separate Muslim electorate under the Morley-Minto reforms of 1909 caused resentment among the Hindus. This was a catalyst for Hindu leaders coming together to create Hindu Mahasabha, an organisation to protect the rights of the Hindu community members, in 1915. The Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating the interests of orthodox Hindus before the British Raj and within the INC. By the 1930s, it would emerge as a distinct party under the leadership of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, developing the far-right ideology of Hindutva (‘Hinduness’) and becoming a fierce opponent of the secular nationalism espoused by the Congress.

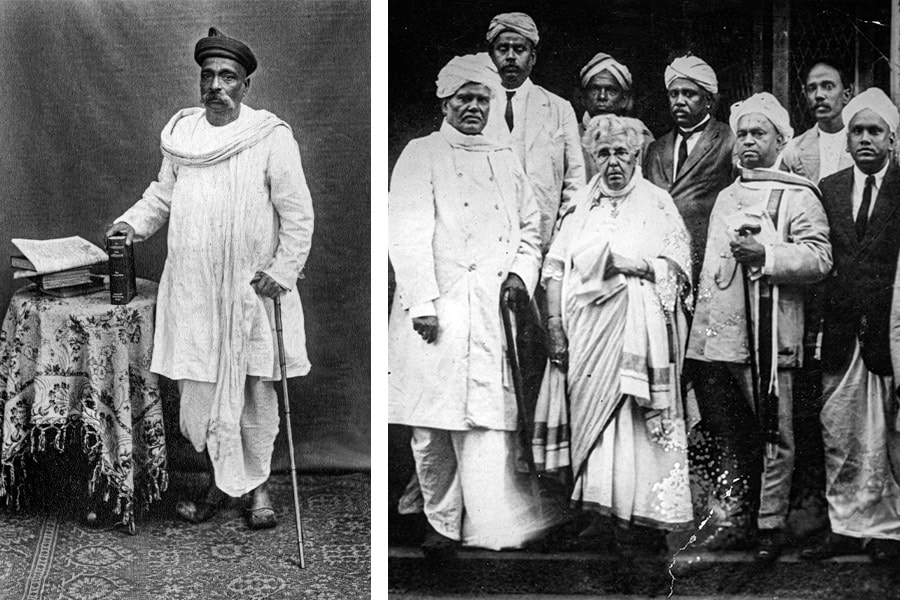

The extremist factions in INC, led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak and an Irish socialist, Annie Besant, spearheaded their separate Home Rule League movements in 1916. Image: Anil Dave/Dinodia Photo; Getty Images

The extremist factions in INC, led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak and an Irish socialist, Annie Besant, spearheaded their separate Home Rule League movements in 1916. Image: Anil Dave/Dinodia Photo; Getty Images

By 1905, there was a clear rift in the INC between moderates in the party and the extremists, who advocated radical methodologies to achieve freedom. The extremist faction, led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak and an Irish socialist, Annie Besant, spearheaded their Home Rule League movement in 1916. The aim of the movement was to achieve self-government in India by its own citizens during British rule. The leagues organised demonstrations and agitations across the country to promote political education and discussion. It garnered huge support from a lot of educated Indians. The Home Rule League merged with the INC party in 1920.

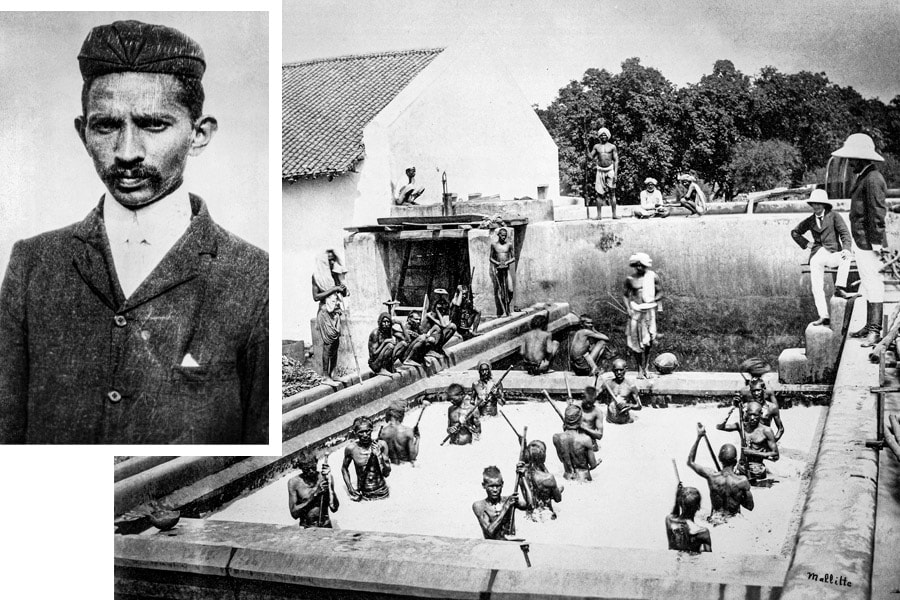

A young activist and lawyer, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress in 1915 after returning from South Africa; Thousands of landless and indentured peasants in Bihar’s Champaran were being forced to grow indigo, paid poorly and taxed heavily by the Brits circa 1917. Image: Bettmann; SSPL/Getty Images

A young activist and lawyer, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress in 1915 after returning from South Africa; Thousands of landless and indentured peasants in Bihar’s Champaran were being forced to grow indigo, paid poorly and taxed heavily by the Brits circa 1917. Image: Bettmann; SSPL/Getty Images

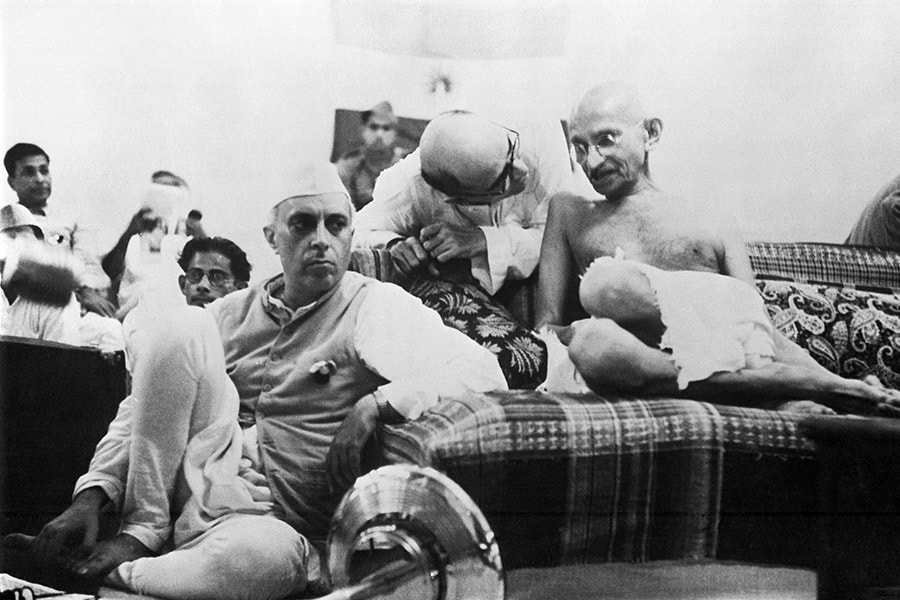

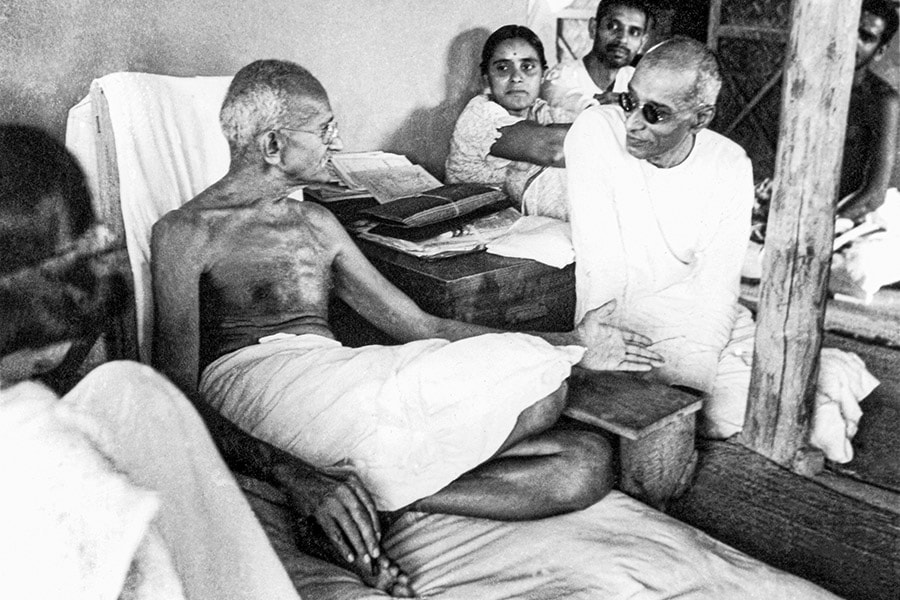

Mohandas Gandhi joined the INC in 1915 after returning from South Africa. By 1920, he was commanding an influence never before attained by any political leader in India. Gandhi revamped the INC into a mass organisation with its roots in small towns and villages. He rallied young leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Dr Rajendra Prasad, C Rajagopalachari, Jayaprakash Narayan, Maulana Kabul Alam Azad and Subhash Chandra Bose and others. Rejecting the new Viceroy’s intention to grant dominion status to India, Gandhi declared that their aim was complete independence.

The Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 was the first peaceful civil disobedience movement led by Mahatma Gandhi, supporting the struggle and revolt of indigo farmers. Thousands of peasants in Bihar’s Champaran, largely landless serfs and indentured labourers, were being forced to grow indigo instead of food crops and were paid for it poorly by landlords while being levied a heavy tax by the Brits, leading to the revolt. Gandhi succeeded in drawing an agreement with the landlords favouring the peasants and setting the framework for future satyagraha.

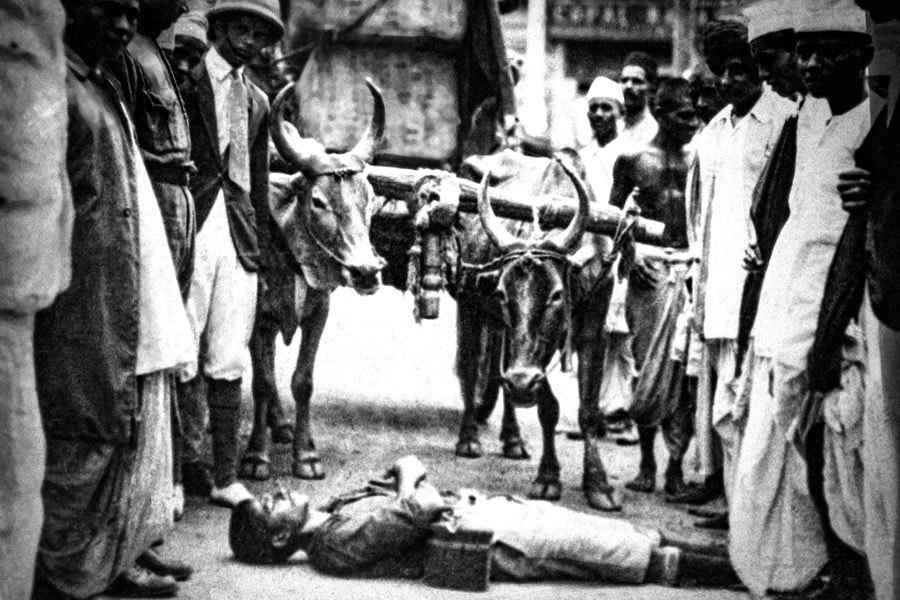

A protestor blocks the way of an ox cart transporting British fabrics from a cargo depot in Bombay during the non-cooperation movement. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

A protestor blocks the way of an ox cart transporting British fabrics from a cargo depot in Bombay during the non-cooperation movement. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Despite fierce Indian opposition, the British passed the Rowlatt Act in February 1919, which empowered the authorities to imprison, without trial, those suspected of sedition. Gandhi promptly announced a satyagraha, and the news of prominent Indian leaders’ arrests sparked violent outbreaks around the country. On April 6, 1919, Gandhi appealed to crowds to remember not to injure or kill British people but to express their frustration in peace, boycott British goods and burn any British clothing they owned.

Also see: India at 75: A Nation in the Making

On April 13, 1919, on the day of Baisakhi, thousands of non-violent protesters, including women and children, gathered in Jallianwala Bagh, a public garden at Amritsar. A martial law had been imposed on Punjab that did not allow groups to gather. Reginald Dyer and his troops blocked the only entrance to the garden and fired on the unarmed crowd without warning, reportedly shooting hundreds of rounds until they ran out of ammunition. It is not certain how many died in the bloodbath, but according to one official report, an estimated 379 people were killed, and about 1,200 more were wounded. Rioting ensued thereafter, and Gandhi went on a fast-unto-death to pressure Indians to desist from violence. The unfolding events, the massacre and the British response led Gandhi to the belief that Indians would never get fair, equal treatment under the British rulers, and he shifted his attention to swaraj and political independence for India.

Women spread the message of using khadi (homespun cloth), using charkhas and boycotting British-made textiles during the non-cooperation movement. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Women spread the message of using khadi (homespun cloth), using charkhas and boycotting British-made textiles during the non-cooperation movement. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

The outrage that spread through the continent led to the launch of the non-cooperation movement by Gandhi on September 5, 1920. The movement was expanded to include the Swadeshi policy—the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. He advocated that khadi (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. Gandhi exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend time each day spinning khadi in support of the independence movement. In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi urged the people to boycott British institutions and law courts, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours. Gandhi thus began his journey aimed at crippling the British India government economically, politically and administratively.

Demonstrators wave one of the first Indian flags adopted in 1921 with a spinning wheel, a symbol of India’s economic regeneration. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Demonstrators wave one of the first Indian flags adopted in 1921 with a spinning wheel, a symbol of India’s economic regeneration. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

The non-cooperation movement in 1920 coincided with the Khilafat movement by the Ali brothers to persuade the British government not to dissolve the Caliphate, the leader of the Islamic world, whom the Muslims regarded as their religious head. Gandhi supported this, and the twin movements saw participation from both Hindus and Muslims, a cooperation that was crucial for political progress against the British in a country where communal disputes and religious riots between the two were common (such as the riots of 1917-18).

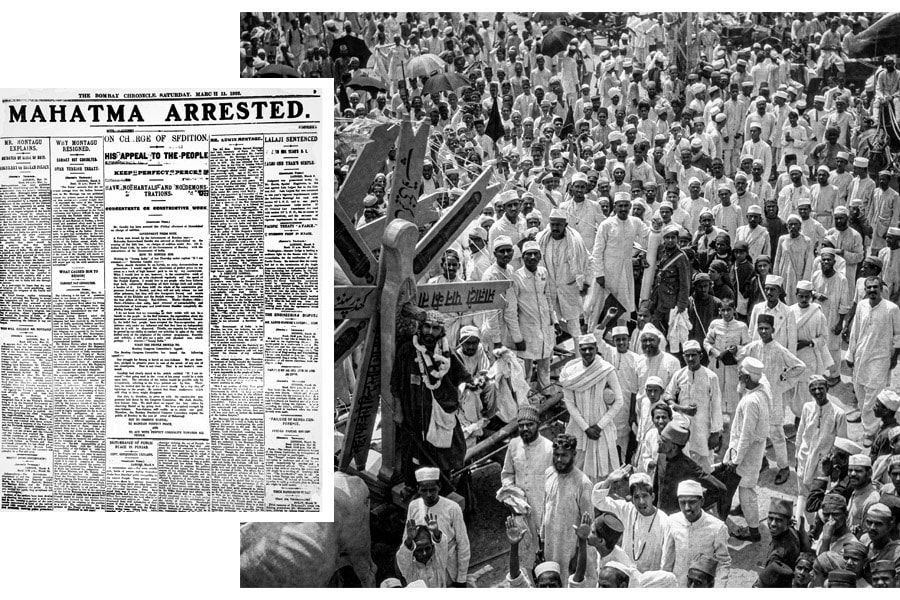

The front page of The Bombay Chronicle of March 11, 1922, reports the arrest of Mohandas Gandhi for sedition; Amidst shouts of ‘swaraj!’, Muslim volunteers protest Gandhi’s arrest. Image: Dinodia Photos/Getty Images; Bettmann

The front page of The Bombay Chronicle of March 11, 1922, reports the arrest of Mohandas Gandhi for sedition; Amidst shouts of ‘swaraj!’, Muslim volunteers protest Gandhi’s arrest. Image: Dinodia Photos/Getty Images; Bettmann

This Hindu-Muslim unity was shortlived as the Khilafat failed, and Gandhi was arrested on March 10, 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to imprisonment. The INC split into two factions, one led by Chittaranjan Das and Motilal Nehru, favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, opposing this move. Muslim leaders left Congress and began forming Muslim organisations. Leaders like Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh began questioning Gandhi’s values and non-violent approach.

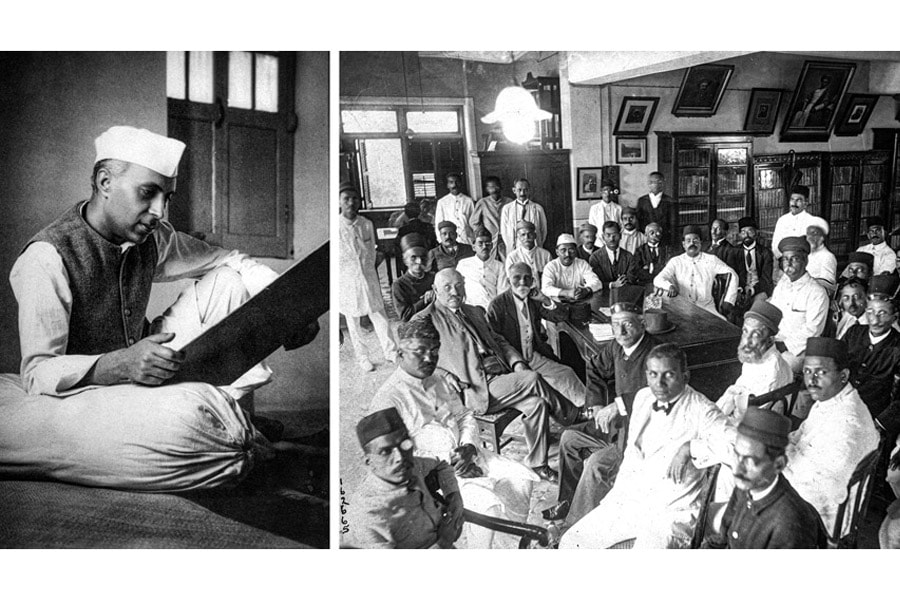

General elections were held in British India in 1920 to elect members to the Imperial Legislative Council and the Provincial Councils. They were the first elections in the country’s modern history. Earlier, two Indian Councils Acts, of 1892 and 1909, allowed a small number of Indians—39 in 1892, rising up to 135 in 1909—to be elected to both the Imperial Legislative Council and the Provincial Legislative Councils. A young Nehru in 1929, who presided over the Lahore session of the Congress;

Members of the Indian National Congress party meeting in 1922, before Gandhi was taken into custody. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images; Getty Images

A young Nehru in 1929, who presided over the Lahore session of the Congress;

Members of the Indian National Congress party meeting in 1922, before Gandhi was taken into custody. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images; Getty Images

At the 1929 Lahore session of the Congress under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, Poorna Swarajya or complete independence, was declared as the party’s goal.

Gandhi picking up a handful of salt at Dandi on April 6, 1930, after walking 385 km over three weeks; Women form a human wall during a demonstration against a repressive salt tax. Image: Ruhe/Ullstein Blid via Getty Images; Bettmann

Gandhi picking up a handful of salt at Dandi on April 6, 1930, after walking 385 km over three weeks; Women form a human wall during a demonstration against a repressive salt tax. Image: Ruhe/Ullstein Blid via Getty Images; Bettmann

The Dandi March, or Salt Satyagraha, was the first act in a far-reaching campaign of civil disobedience (satyagraha) that Gandhi waged against British rule. Salt production and distribution in India had long been a lucrative monopoly of the British. Through a series of laws, Indians were prohibited from producing or selling salt independently. Instead, Indians were required to buy expensive, heavily taxed salt that often was imported. The salt tax accounted for 8.2 percent of the British Raj revenue from the tax.

A soldier under British command beats satyagrahis with a lathi at Wadala salt pans while they spirit away some salt without paying tax in defiance of laws. Image: Bettmann

A soldier under British command beats satyagrahis with a lathi at Wadala salt pans while they spirit away some salt without paying tax in defiance of laws. Image: Bettmann

In early 1930 Gandhi decided to protest against the increasingly repressive salt tax by walking from Sabarmati to the town of Dandi near Surat on the Arabian Sea coast. He set out on foot on March 12, along with his followers. With each day’s march, hundreds more would join as they made their way to the sea. On the morning of April 6, after a journey of some 385 km, Gandhi and his followers reached the sea at Dandi and picked up handfuls of salt along the shore, thus technically ‘producing’ salt and breaking the law. No arrests were made that day, and Gandhi continued his satyagraha against the salt tax for the next two months, exhorting other Indians to break the salt laws by committing acts of civil disobedience.

Satyagrahis make salt by the sea in Madras, defying the government. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Satyagrahis make salt by the sea in Madras, defying the government. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Thousands were arrested and imprisoned, including Gandhi himself, in early May. News of Gandhi’s detention spurred tens of thousands more to join the satyagraha. By the end of the year, some 60,000 people were in jail. The government tried to suppress the movement with more laws and censorship. The Congress Party was declared illegal.

Gandhi and Madan Mohan Malaviya at the second Round Table Conference to discuss Indian constitutional reform in Westminster, London, in September 1931. Image: Woodbine/Mirrorpix/GettyImages

Gandhi and Madan Mohan Malaviya at the second Round Table Conference to discuss Indian constitutional reform in Westminster, London, in September 1931. Image: Woodbine/Mirrorpix/GettyImages

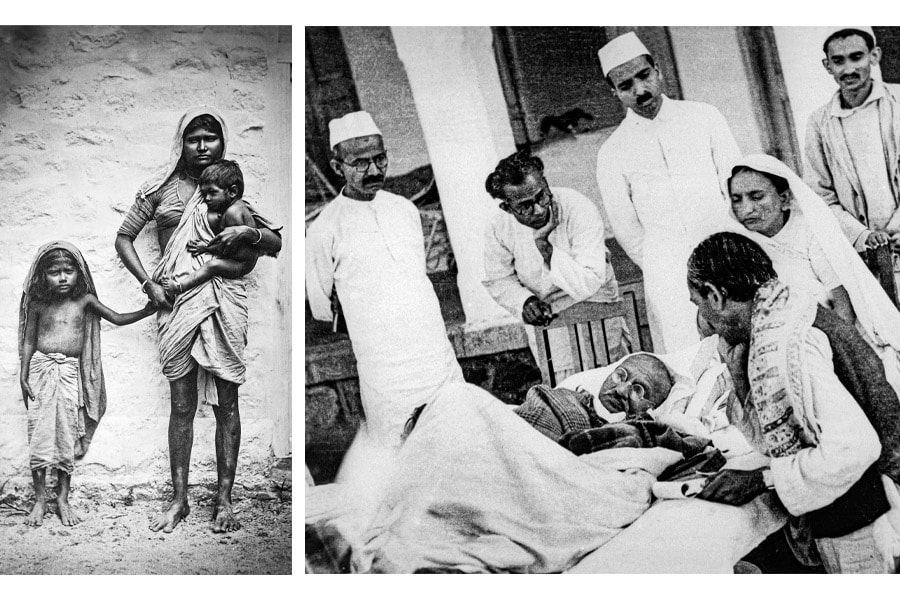

Gandhi was released from custody in January 1931 and began negotiations with Lord Irwin aimed at ending the satyagraha campaign. The Gandhi-Irwin Pact was signed on March 5, allowing Indians to make salt for domestic use. The settlement paved the way for Gandhi, representing the Indian National Congress, to attend the second session (September–December 1931) of the Round Table Conference in London as an ‘equal’.  A portrait of a Harijan mother and her children circa the 1930s; Gandhi often embarked on fasts. Here, he protests the government’s segregation and allotment of separate electorate for Harijans (untouchables) circa 1939. Image: Bettmann; Ruhe/Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

A portrait of a Harijan mother and her children circa the 1930s; Gandhi often embarked on fasts. Here, he protests the government’s segregation and allotment of separate electorate for Harijans (untouchables) circa 1939. Image: Bettmann; Ruhe/Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

In September 1932, again a prisoner, Gandhi embarked on a fast to protest the British government’s decision to segregate the so-called ‘untouchables’ by allotting them separate electorates in the new constitution. The fast became the starting point of a robust campaign for the removal of the disempowerment of Dalits, whom Gandhi referred to as Harijans, or ‘children of God’.

Indian soldiers far away from home in Eritrea during World War 2, 1st April 1940. Image: Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Indian soldiers far away from home in Eritrea during World War 2, 1st April 1940. Image: Mirrorpix via Getty Images

During the Second World War (1939–1945), Viceroy Linlithgow—without consulting with Indian political leaders —declared that British India would go to war against Nazi Germany. He sent over two and a half million Indian soldiers to fight under British command against the Axis powers around the globe. The Congress, the largest and most influential political party, demanded independence before it would support the British war effort, while the Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha supported the British.

Gandhi confers with his secretary Mahadev Desai during the AICC meet to launch the historic Quit India movement of 1942. Image: Bettmann

Gandhi confers with his secretary Mahadev Desai during the AICC meet to launch the historic Quit India movement of 1942. Image: Bettmann

London refused, and the Congress, led by Gandhi, gathered at Mumbai’s Gowalia Tank Maidan on August 8, 1942, to launch the Quit India Movement to bring an immediate end to British rule over India. The British government responded by banning INC and arresting the party’s high command—Gandhi, Nehru, Patel—the very next day. This left the movement in the hands of younger leaders like Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Manohar Lohia and Aruna Asaf Ali.

An injured protestor is taken away as Quit India movement protests in Bombay turn violent. Image: New York Times Co/Getty Images

An injured protestor is taken away as Quit India movement protests in Bombay turn violent. Image: New York Times Co/Getty Images

Over the next few months, thousands of Indians were killed and wounded, and many more arrested, but resistance continued as more young Indians, women as well as men, were recruited into the Congress’s underground.

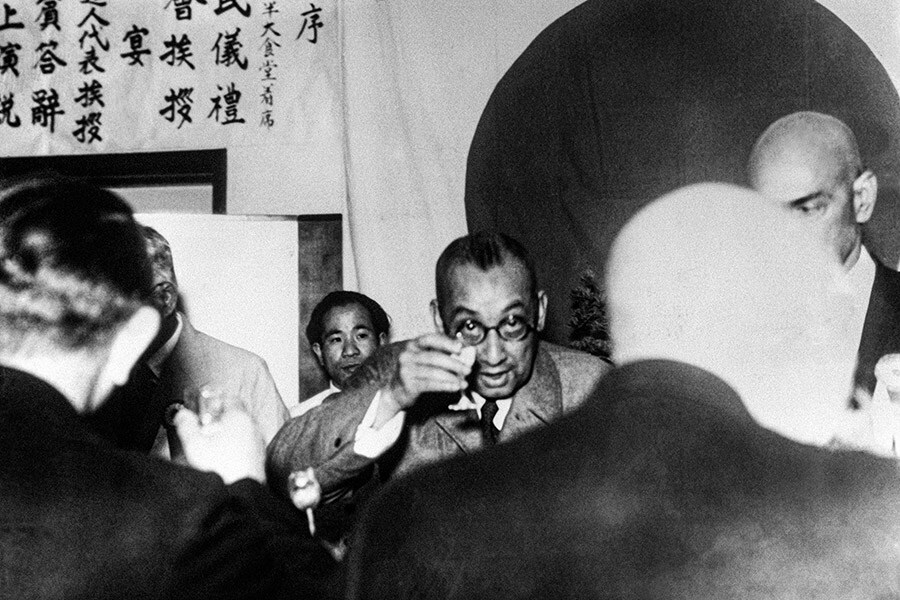

Subhas Chandra Bose at a dinner offered in his honour in Tokyo, Japan in 1943. Critical of Gandhi, Bose sought Japanese aid to form an army to liberate India. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Subhas Chandra Bose at a dinner offered in his honour in Tokyo, Japan in 1943. Critical of Gandhi, Bose sought Japanese aid to form an army to liberate India. Image: Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

Indian leader Subhas Chandra Bose and Japan set up an army of Indian POWs known as the Indian National Army, which fought against the British. A major famine in Bengal in 1943 led to the deaths of millions from starvation and the widely debated issue of Churchill’s blatant disregard for emergency food relief. However, there was opposition to the Quit India movement from the Muslim League, the Communist Party of India and the Hindu Mahasabha. The Muslim League was not in favour of the British leaving India without partitioning the country first.

A British family stepping into a dugout air raid shelter, 1939. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

A British family stepping into a dugout air raid shelter, 1939. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

Britain was facing pressure from the US and other allied leaders over its own imperial policies in India and to secure Indian cooperation for the Allied war effort. Under duress from national movements led by the INC, the war-weakened British were forced to consider leaving India. In response to the Congress campaign that Britain quit India, London sent a mission headed by Sir Richard Stafford Cripps to New Delhi in March 1942. The mission offered a full “dominion status” for India after the war’s end, with the added clause, as a concession primarily to the Muslim League, that any province could vote to “opt-out” of such a dominion if it preferred to do so. This proposal seemed damaging to national unity. The Congress and other parties rejected it and insisted on an immediate transfer of power while the war raged. This produced an impasse and the failure of the mission.

C Rajagopalachari’s Formula of 1944 first acknowledged the inevitability of Partition. Image: Dondia Photos/Getty Images

C Rajagopalachari’s Formula of 1944 first acknowledged the inevitability of Partition. Image: Dondia Photos/Getty Images

The Rajaji Formula of 1944 was the first acknowledgement by a Congressman about the inevitability of the partition of the country and a tacit acceptance of Pakistan. The League was increasingly demanding a separate nation for the Muslims, whereas the INC was against the partitioning of the country. To break the deadlock, C Rajagopalachari, who was close to Mahatma Gandhi, proposed a set of plans. The proposals were thus: The Muslim League would join hands with the INC to demand independence from the British and cooperate to form a provisional government at the centre. All the inhabitants (Muslims and non-Muslims) in these areas would vote to decide on forming a separate sovereign nation (or not), all of these being conditional upon Britain transferring full powers to India.

The talks between Gandhi and Jinnah were a failure as Jinnah had objections to the proposal. He wanted the INC to accept the Two-Nation Theory (that Indian Muslims were entitled to a separate, self-governing state in a reconstituted subcontinent) and wanted separate dominions to be created before the English left India. The Sikhs also looked upon the formula unfavourably as it meant a division of Punjab. Although the Sikhs were a big chunk of the population, they were not in the majority in any of the districts. V D Savarkar and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee of the Hindu Mahasabha and Srinivas Sastri of the National Liberal Federation were also against the Rajaji Formula.

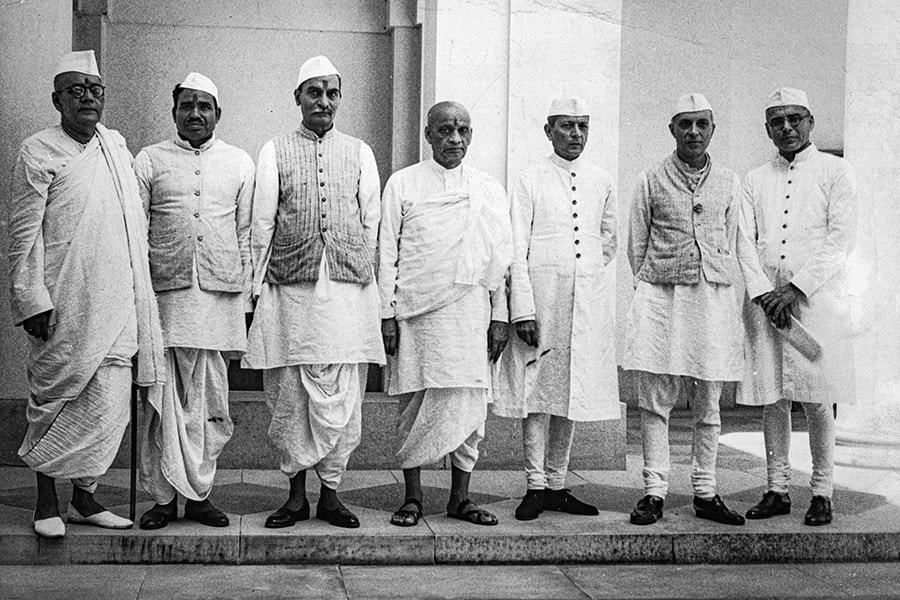

Members of Executive Council of the Interim Government 1946 (from left) Sarat Chandra Bose, Jagjivan Ram, Dr Rajendra Prasad, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Asaf Ali, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Syed Ali Zaheer. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

Members of Executive Council of the Interim Government 1946 (from left) Sarat Chandra Bose, Jagjivan Ram, Dr Rajendra Prasad, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Asaf Ali, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Syed Ali Zaheer. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

In Britain, the new post-war Labour Party government of Clement Attlee that succeeded the Conservative Winston Churchill government was determined to end its authority in India. A cabinet mission led by William Pethick-Lawrence was sent in 1946 with the hope of resolving the Congress–Muslim League deadlock and planning the transfer of power from the British Raj to a single Indian administration. The Mission proposed a three-tier structure: A centre, groups of provinces, and provinces. The ‘groups of provinces’ were meant to accommodate the Muslim League's demand.

Muslim League members gather to show their support for the interim government in 1946. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Getty Images

Muslim League members gather to show their support for the interim government in 1946. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Getty Images

Both the Muslim League and Congress, in principle, accepted the Cabinet Mission’s plan. Days later, a speech by Nehru that effectively stated that Congress was neither bound nor committed to the plan was seen as treachery by Jinnah. The Muslim League withdrew its consent to the plan in July 1946 and decided to launch ‘Direct Action’ to achieve Pakistan and organise the Muslims for the coming struggle. Jinnah, in the concluding session of the Council of Muslim League, declared, “Today we bid goodbye to constitutional methods….”

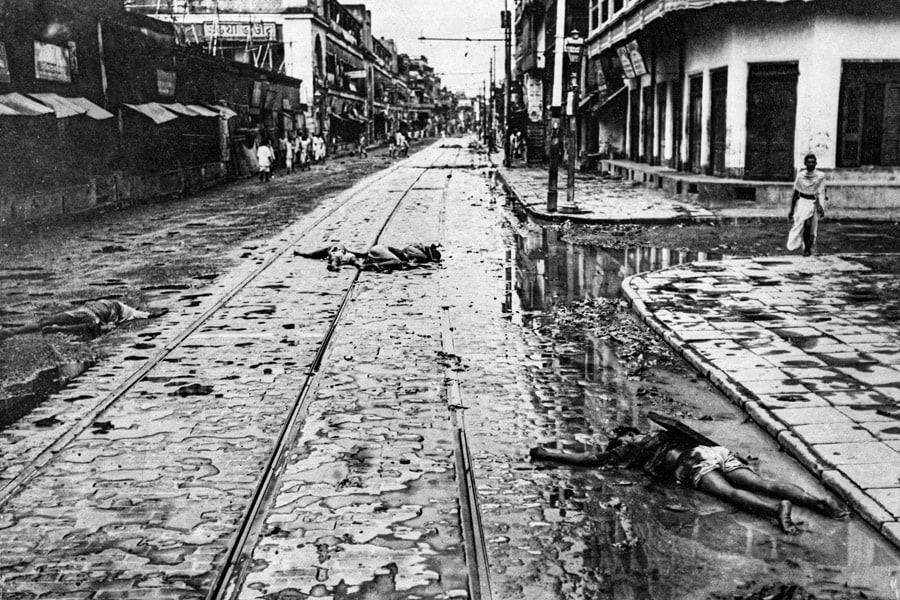

The communal rioting began with Muslim League’s Direct Action Day in Calcutta on August 16, 1946, to demand a separate dominion. Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

The communal rioting began with Muslim League’s Direct Action Day in Calcutta on August 16, 1946, to demand a separate dominion. Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

Jinnah called for ‘Direct Action Day’ on 16 August 1946 in Bengal, the only province under Muslim League’s rule. Trouble started on the morning of August 16 in Calcutta, where the League leaders’ fiery anti-Hindu speeches at a rally got the massive crowds excited. Thus began India’s bloodiest year of civil war since the mutiny nearly a century earlier. The communal rioting and killing that started in Calcutta ravaged Noakhali and spread to the rest of Bengal, Bihar and other parts of Northern India over many days, leaving over 4,000 people dead and a further 1,00,000 homeless, sending deadly sparks of fury, chaos, and fear to corners of the subcontinent.

Pakistani leaders Liaquat Ali Khan and Muhammad Ali Jinnah visiting the India Office in London in December 1946. Image: Keystone/Getty Images

Pakistani leaders Liaquat Ali Khan and Muhammad Ali Jinnah visiting the India Office in London in December 1946. Image: Keystone/Getty Images

For the first time, several leaders of the Congress Party, who had initially opposed partition, thought it a solution to do away with Jinnah and the Muslim League. The British, having lost any remaining vestiges of control, started speeding up their exit strategy. British Prime Minister Clement Atlee announced on the afternoon of 20 February 1947 before Parliament that British rule would end on “a date not later than June 1948”.

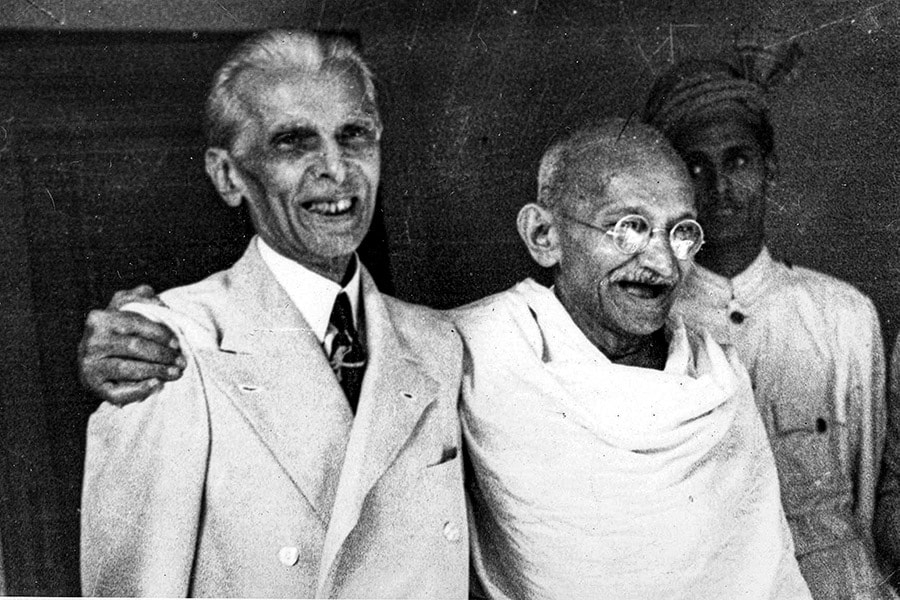

Despite the camaraderie, talks between Jinnah and Gandhi failed in October 1946 as there was anxiety that the Hindu majority would dominate the Muslims. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Despite the camaraderie, talks between Jinnah and Gandhi failed in October 1946 as there was anxiety that the Hindu majority would dominate the Muslims. Image: Universal History Archive/Getty Images

In the aftermath of the communal riots, Gandhi and Jinnah met for talks and presented the Gandhi-Jinnah formula, which stated thus: “The Congress does not challenge and accepts that the Muslim League is now the authoritative representative of an overwhelming majority of the Muslims of India. In accordance with democratic principles, they alone have an unquestionable right to represent the Muslims of India.”

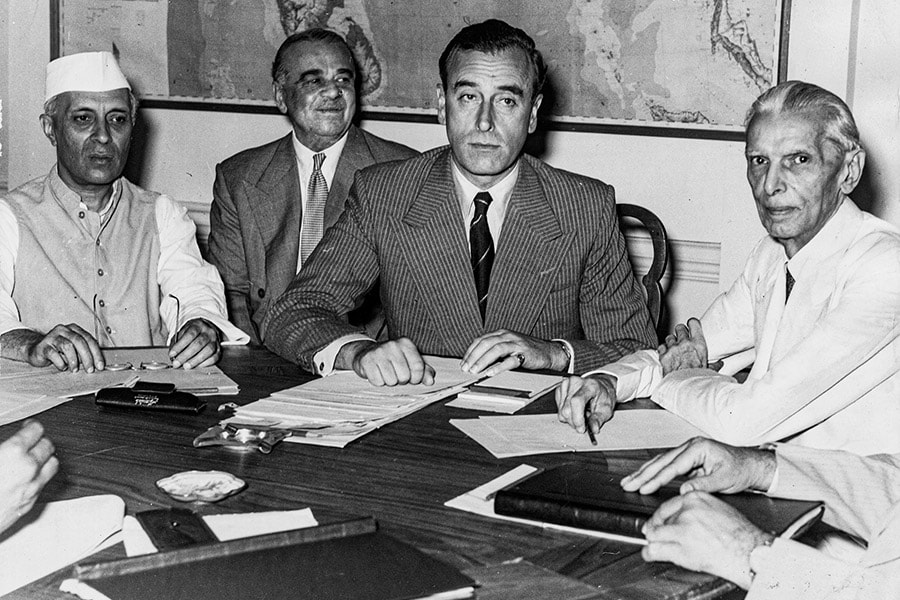

At the meeting of Britain’s partition plan for India (from left) Indian Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru, Lord Ismay, Viceroy of India Lord Louis Mountbatten and All-India Muslim League President Muhammad Ali Jinnah, March 1947. Image: Keystone/Getty Images

At the meeting of Britain’s partition plan for India (from left) Indian Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru, Lord Ismay, Viceroy of India Lord Louis Mountbatten and All-India Muslim League President Muhammad Ali Jinnah, March 1947. Image: Keystone/Getty Images

On 14th August 1947, India was partitioned along communal lines into the dominions of India and Pakistan. Sir Cyril Radcliffe divided the roughly 4,50,000 sq km of territory between the two dominions. Neither the Indian leaders nor the British were prepared for or anticipated the massive scale of the Partition.

Muslim refugees board a train to Pakistan upon the Partition of India, one of the greatest mass migrations in modern history, on August 14, 1947. Image: Daily Herald Archive/NS&MM/SSPL via Getty Images

Muslim refugees board a train to Pakistan upon the Partition of India, one of the greatest mass migrations in modern history, on August 14, 1947. Image: Daily Herald Archive/NS&MM/SSPL via Getty Images

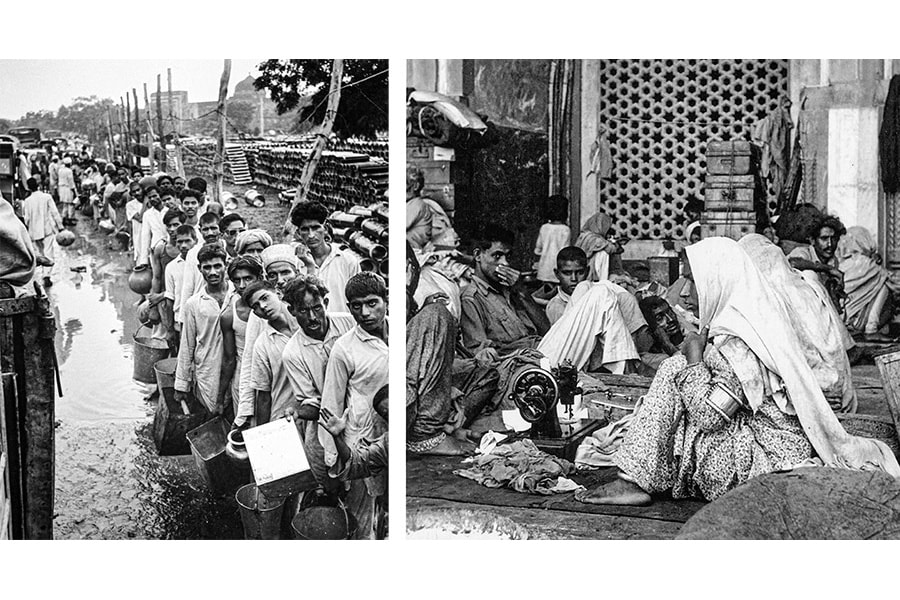

It sparked one of the greatest mass migrations in modern history, on foot, in bullock carts and by train. In the saga that saw roughly 15 million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs move from one side of the subcontinent to the other, leaving their immoveable assets behind, families were uprooted from the soil of their ancestors, many were lost or slaughtered in communal massacres that ensued, women were raped or abducted and the refugee camps overflowed with people who were left with bare belongings.  Muslim refugees wait in line for a jar of water at a camp in Purana Qila in Delhi, where they have taken refuge from riots that ensued after Partition, 25 September 1947; A young family with bare belongings takes shelter at a Delhi monument, circa August 1947. Image Bettmann; AFP

Muslim refugees wait in line for a jar of water at a camp in Purana Qila in Delhi, where they have taken refuge from riots that ensued after Partition, 25 September 1947; A young family with bare belongings takes shelter at a Delhi monument, circa August 1947. Image Bettmann; AFP

The Sikhs, crossing over their new dividing line, suffered the highest proportion of casualties relative to their numbers. An unforeseen consequence of Partition was that Pakistan’s population ended up more religiously homogeneous than anticipated, with a minuscule number of non-Muslim minorities. While a sizeable number of Muslims never supported the migration and stayed back, making it the largest minority group in India.

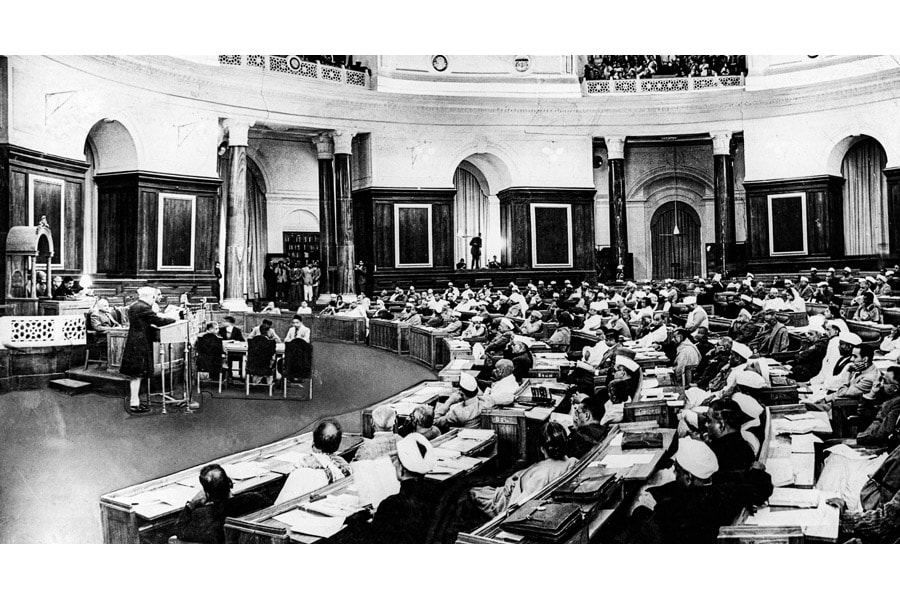

At the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi, Pandit Nehru moves the resolution for an independent Sovereign Republic on January 22, 1947. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

At the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi, Pandit Nehru moves the resolution for an independent Sovereign Republic on January 22, 1947. Image: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

A spontaneous exhibition of joy and happiness erupted around the country on 15 August 1947 as Jawaharlal Nehru became the first Prime Minister of India and raised the Indian national flag above the Lahori Gate of the Red Fort in Delhi in honour of the celebrations. Missing from the festivities was Gandhi, who opposed the partition of India and Pakistan, who was in the midst of a fast that he hoped would bring an end to the violence between the Hindus and Muslims.

Crowds on streets of Bombay celebrate the handing over of power in India with illuminations and fireworks, August 21, 1947. Image: Central Press/GettyImages

Crowds on streets of Bombay celebrate the handing over of power in India with illuminations and fireworks, August 21, 1947. Image: Central Press/GettyImages

On the night of 14 August 1947, thousands of Indians gathered near government buildings in Delhi for the official ceremony celebrating independence from Britain. India chose to become a secular country. Jawaharlal Nehru, who would become the first prime minister of India, addressed the crowd an hour before midnight. “Long years ago, we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially,” he said. “At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

A delegation of Sikhs leaves Downing Street, London, after presenting a petition calling for the whole of the Punjab region to be included in the state of India on August 8, 1947. Image: Central Press/Getty Images

A delegation of Sikhs leaves Downing Street, London, after presenting a petition calling for the whole of the Punjab region to be included in the state of India on August 8, 1947. Image: Central Press/Getty Images

The cementing of a communal divide which was the tragic legacy of Partition, continues to wrathfully shadow an independent India, a bittersweet dream that haunts the waking hours of the progressive Indian.

Sources & acknowledgements: International Center on Nonviolent Conflict; NCERT; British Library; India’s struggle for Independence 1857 -1947 Ed. Bipan Chandra / Penguin; BBC History; The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company William Dalrymple / Bloomsbury; Encyclopaedia Britannica.