How to create enduring social impact

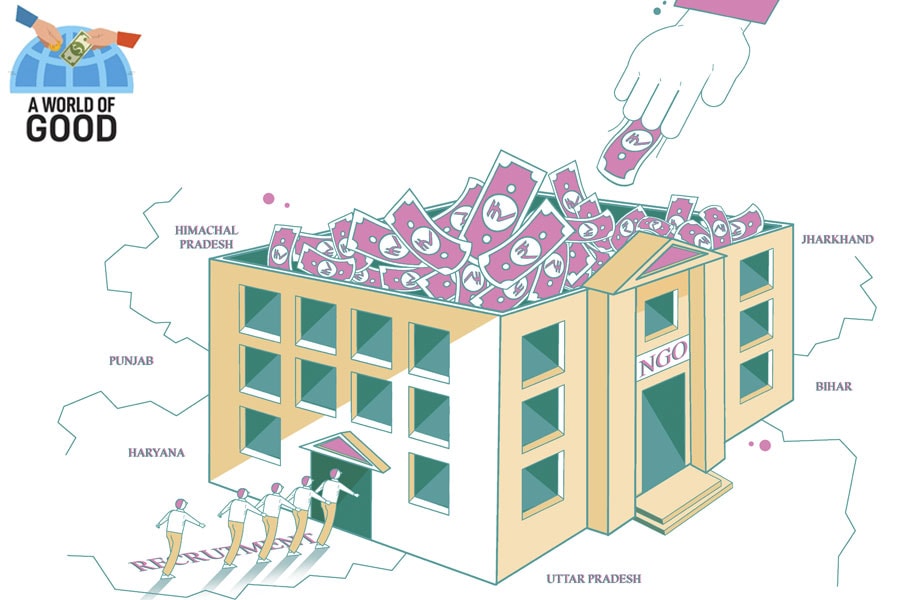

India's NGOs would benefit enormously from reserves and endowments that could translate to financial resilience, and much more significant impact, Pritha Venkatachalam and Anant Bhagwati of The Bridgespan Group write

NGOs in India struggle with financial resilience. The Pay What It Takes (PWIT) India initiative has shown us that even tenured, larger-sized NGOs lack operating reserves, let alone an endowment.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

NGOs in India struggle with financial resilience. The Pay What It Takes (PWIT) India initiative has shown us that even tenured, larger-sized NGOs lack operating reserves, let alone an endowment.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

For Mumbai-based Jai Vakeel Foundation (JVF), 2019 was a pivotal year. Even though the NGO was emerging as a leader in the field of intellectual disability, it was struggling to make ends meet. That was until it built its target corpus—a large sum mobilised from multiple funders to provide many months of operating costs. This key moment allowed the NGO to unlock its potential.

Back then, JVF served 700 students directly with a staff of about 200 and an annual expense budget of ₹11.25 crore ($1.6 million). It supported an additional 2,000 students per year through two rural medical camps.

Back then, JVF served 700 students directly with a staff of about 200 and an annual expense budget of ₹11.25 crore ($1.6 million). It supported an additional 2,000 students per year through two rural medical camps.

When Archana Chandra, who had been with the organisation since 2009, took over in 2013 as CEO, she knew the institute’s financial base had to expand. JVF, established in 1944, had historically been funded through the largesse of the founder’s extended family and their personal networks. At the time, JVF “had two sources of funding: The government and a few individual donors,” says Payal Wadhwa, JVF’s head of fundraising and donor management. “Today, there is government funding, support from trusts and corporates, individual funding, and more.”

It was imperative, Chandra knew, to change how funders viewed JVF. The answer came in the form of a crucial fundraising exercise envisioned as the ‘Champions of Change’ campaign, which would help JVF build a corpus. The campaign involved getting pledged commitments from supporters. The generosity of significant donors was acknowledged and celebrated by works of art created by noted sculptor Arzan Khambatta. JVF then collaborated with other prominent artists, who painted Khambatta’s sculptures in their own unique styles.