Chandrayaan-3: Kartikeya V Sarabhai on his family's legacy from textiles to space research

Vikram Sarabhai was nurtured and grew up at a time when there was a tradition of not thinking only of business as your business but doing things for the country and larger society as also your calling, your work, your business, Kartikeya V Sarabhai, writes

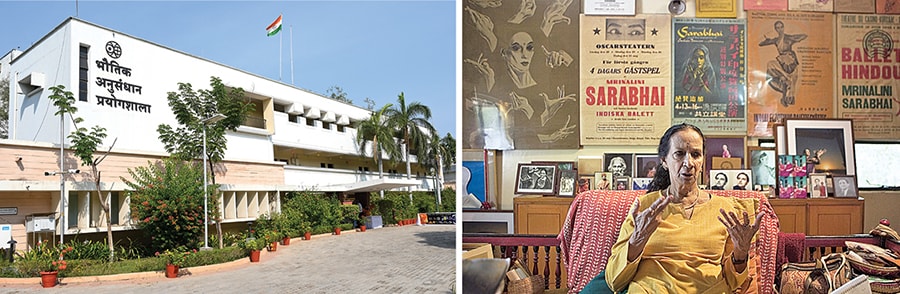

(Clockwise from top) The Sarabhai family; Vikram Sarabhai with son Kartikeya; Mallika (extreme left), Mrinalini, Kartikeya and Vikram (right)

Image: Courtesy Sarabhai Family

(Clockwise from top) The Sarabhai family; Vikram Sarabhai with son Kartikeya; Mallika (extreme left), Mrinalini, Kartikeya and Vikram (right)

Image: Courtesy Sarabhai Family

On August 23, as the time approached 6.04 pm, the nation held its breath. Each of those last few minutes seemed long and there was a lot of understandable tension. My 11-year-old grandson Kavan held my arm tight as we sat in anticipation, glued to the television. Finally, Vikram landed, softly and exactly as it was supposed to. There was a spontaneous outburst of joy wherever the cameras could take their viewers. The phones started to ring. Media channels wanted a sound bite. “How did you feel?” was one of the first questions. “Like every other proud Indian”, I would reply, “full of admiration for the team at ISRO which had so meticulously and without much hyperbole conducted a very difficult operation, one which no other country had done before”. The lander did carry my father’s name in respect of his contribution to establishing the Indian Space Agency, but he belonged to all of us.

Young Vikram Sarabhai was fortunate. Born in what was then one of the leading industrialist families, his passion for science was encouraged by his parents. A small lab was set up, under the water tank, at The Retreat, the family estate in Shahibag, Ahmedabad. Never was there any pressure to only focus on the business which was then largely textiles—the Calico mill was one of the largest in the city. That tradition of not thinking only of business as your business but doing things for the country and for the larger society as also your calling, as also your work, your business was quite unique and rare.

Young Vikram Sarabhai was fortunate. Born in what was then one of the leading industrialist families, his passion for science was encouraged by his parents. A small lab was set up, under the water tank, at The Retreat, the family estate in Shahibag, Ahmedabad. Never was there any pressure to only focus on the business which was then largely textiles—the Calico mill was one of the largest in the city. That tradition of not thinking only of business as your business but doing things for the country and for the larger society as also your calling, as also your work, your business was quite unique and rare.

Ambalal Sarabhai himself belonged to a wealthy family in the city. His grandfather Maganbhai, otherwise a merchant, was known for his love of trees. He started the first girls’ schools in Ahmedabad in 1851. It was Ambalal’s father who, at the young age of 18, took responsibility for running the Calico mill in 1880. Calico was a small unit then. He died at a very young age. Ambalal who inherited this responsibility was determined to modernise the textile mill. He spent time in England studying modern textile manufacturing at Lancashire in the UK. Working with cutting-edge technology and bringing to India what was best in the world was another characteristic of the way the family saw their mission. In 1937, Calico erected India’s first Diamond Mesh Mosquito Netting plant.

Ambalal had helped his sister Anasuya to go to London and study at the London School of Economics. When she returned, she started working with the children of textile workers. In 1917, there was a plague epidemic in Ahmedabad. To help the workers, mills in Ahmedabad had started to give a plague allowance along with the salary. But, by 1918, the plague was over and the millowners wanted this allowance removed. The workers resisted and it soon led to a general strike. Ambalal was the head of the Millowners Association, and Anasuya was leading the workers. The brother and sister, while leading opposite sides, would still eat together at night. Nowhere did the family question whose was the right ‘business’? The legitimacy of both stands and actions were equal, even in the eyes of each other. Finally, the strike ended with a formula worked out by Gandhiji, who had returned to India just a few years before this and set up his ashram on the banks of the Sabarmati.

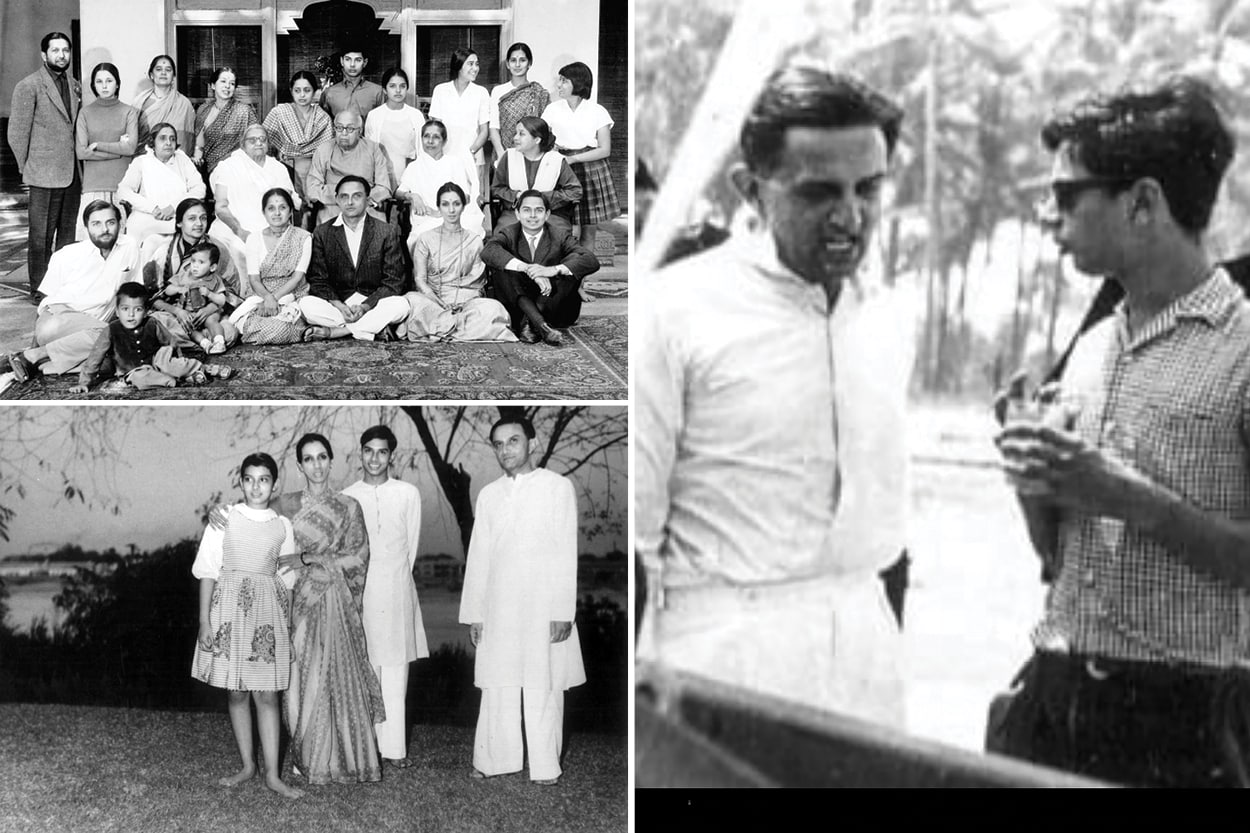

Staff members of Vikram Sarabhai Community Science Centre in Ahmedabad

Image: Sam Panthaky / AFP

Staff members of Vikram Sarabhai Community Science Centre in Ahmedabad

Image: Sam Panthaky / AFP