Uday Shankar: Making Star shine

Uday Shankar's appointment as CEO of Star India was an unexpected but inspired choice. Consider the meteoric rise of the media company under a former journalist

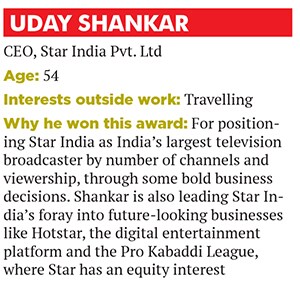

Forbes India Leadership Award: Best CEO – MNC

The corner office on the 37th floor of Urmi Estate, an erstwhile textile mill that has been redeveloped into a skyscraper in Mumbai’s Lower Parel area, is an unusual workspace. It is large enough by Mumbai standards to accommodate a studio apartment (with a breathtaking view of the Arabian Sea), but is conspicuous in the absence of a sprawling desk and a leather-bound chair behind it.

But, then, there is nothing usual about the man who occupies this office. Uday Shankar, the 54-year-old chief executive of Star India, works behind a standing desk (famously preferred by the likes of former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and authors Virginia Woolf and Ernest Hemingway). Standing upright while working helps him keep fit and think better, says Shankar. It has certainly helped him keep Star India, the country’s largest television broadcaster, in good shape.

The meteoric growth in Star’s size and stature in India under Shankar’s stewardship has made him a blue-eyed boy for the Murdochs, especially 21st Century Fox’s new chief executive and Rupert Murdoch’s son James Murdoch. According to industry estimates (Star operates through multiple entities in India and since all of them are unlisted, their financials aren’t available publicly), Star’s turnover has grown fivefold in the eight years that Shankar has been at the helm to Rs 8,500 crore at the end of FY15. Its market share, in terms of cumulative television viewership in India, has also doubled to 24 percent in this period. Though Star’s profitability couldn’t be ascertained, James Murdoch has gone on record to say that Star India aims to report an operating profit of $1 billion (around Rs 6,650 crore) by 2020.

A Morgan Stanley report issued in August this year values Star India at $11.2 billion, making it the most valued broadcast network in India, with over 40 channels spanning genres like sports, movies and entertainment across seven languages, reaching more than 720 million viewers each week across 100 countries. It also operates the digital entertainment platform Hotstar and owns sports leagues like the Pro Kabaddi League.

This growth demanded big, bold steps and Shankar, while an unlikely CEO, certainly wasn’t a reluctant one.

In 2007, when the Murdochs were looking for a successor to the then Star India CEO Peter Mukerjea, Shankar was a surprising choice. Consider that he is a former journalist with a Master’s degree in economic history from Delhi’s prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University. Not many journalists were made CEOs of media companies at that time.

Shankar, who hails from Patna in Bihar, originally aspired to be a civil servant but failed an interview that would have allowed him to pursue this profession. Since childhood, Shankar was inquisitive and loved to travel (an expensive hobby in those days). He channelled his curiosity to pursue a career in journalism, which, he hoped, would allow him scope to travel. The son of a civil engineer, Shankar cut his teeth in journalism as a political correspondent for The Times of India in Patna. He moved to Delhi thereafter and worked for a few publications (including the environment-focussed Down To Earth magazine, of which he was a founding member) before shifting to television journalism in 1995, when it was just about opening up for the private sector in India. He started out as a news producer for Zee TV and worked for a slew of TV channels after that, including as editor and news director at Aaj Tak and then as chief executive of Media Content and Communication Services India Pvt Ltd (MCCS)—a joint venture between the Kolkata-based ABP Group and Star India—the company that operated the Hindi news channel, Star News (which has since been renamed ABP News).

He joined MCCS in 2004. It was during his stint at MCCS, which was based out of the same office building in Mumbai’s Mahalakshmi area as Star India at that time, that Shankar caught the Murdochs’ attention. The company was struggling before Shankar assumed the top job, and he managed to turn things around, positioning Star News as a leading Hindi general news channel in India. This earned him precious goodwill within Star’s ecosystem, Shankar says. And that was to come in handy.

Between 1999 and 2006, Star Plus, the group’s Hindi general entertainment channel, had a great run in India. Soap operas like Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi and Kahaani Ghar Ghar Kii, produced by Ekta Kapoor-led Balaji Telefilms, and gameshows like Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC), anchored by Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan, generated high viewership and advertiser interest.

But subsequent lack of innovation in programming and new rivals who brought in fresh content saw Star Plus’s dominance being seriously challenged. Viewership and ad revenues started waning, so much so that it set the alarm bells ringing in the regional head office in Hong Kong and the global headquarters in New York.

According to a Business Standard article that appeared in June 2012, on one of his trips to India, the then News Corp COO Peter Chernin met Shankar and asked him for his opinion on what ailed Star India (News Corp has since been restructured with the television and film studio business being housed under 21st Century Fox and newspapers and other publishing assets continuing under the restructured News Corp). Shankar didn’t mince words and was soon called to Hong Kong and asked to take over the network.

His association with a couple of successful television ventures like Aaj Tak and Star News in the past stood him in good stead, says Shankar. “Star used to be a very successful network but it faced some of the challenges that, I assume, all successful companies face sooner or later,” Shankar told Forbes India. “It stopped innovating as much as it should have. It stopped pushing the creative boundaries and a whole bunch of new competitors mounted a stiff challenge.”

When he was appointed CEO of Star India in October 2007, he not only had the challenge of fixing the company, but also of battling perception, since not many journalists were made CEOs of media companies. Not many understood why he was being handed the reins of the television network. Some even speculated that Shankar’s appointment was an indication that the Murdochs had all but given up on the India business and may exit soon. More than within the company, there were “loud noises” outside surrounding his appointment as CEO, as people thought he had bitten off more than he could chew, Shankar recalls.

In fact, he too was flattered and surprised—not because he doubted his own capabilities but because he didn’t fit the profile of a typical CEO armed with a management degree and sales experience. He wasn’t even a keen follower of the kind of soap operas and dramas that used to air on Star Plus and didn’t know anything about that format of TV programming, he admits. But being a newcomer helped him, as he approached everything with a “fresh pair of eyes”. He was aided in this endeavour by his training as a journalist, which taught him to decode diverse and complex real-life situations, while paying close attention to minute details and asking the right questions. Shankar looked at each piece of the business and evaluated what needed to be changed.

“Uday came in with a fresh, new perspective to the business and it helped that he wasn’t a traditional media or advertising person,” says CVL Srinivas, CEO, South Asia, GroupM, the world’s largest media investment group. “He brought in a certain kind of dynamism at Star that is difficult for large companies to consistently exhibit. He is a pretty disruptive thinker.”

Shankar was acutely conscious that while he understood content and consumer sentiment very well, he didn’t have all the requisite skills for other business functions like finance and operations. So he spent a large part of his time, in the initial years, building a strong team around him.

The next task for the new CEO was to yank Star out of its comfort zone, which was characterised by the continuous airing of a few shows that had done well for the network in the past: For instance, KBC and those produced by Balaji Telefilms, a company in which Star had an equity stake and an exclusive content tie-up. “Shows like KBC were becoming our silver bullets. Each time we had a drop in ratings, we would do another season of the game show. This wasn’t working. We were a creative company but we had outsourced our creativity,” says Shankar.

One of the first things that Shankar did after taking charge was to surrender the rights to KBC. Shankar admits that everyone around him felt this was a “suicidal move” at that time and may even have led to short-term pain for Star, but “I realised that as long as we had KBC, we won’t be wearing our thinking hats to look for new content,” he says.

Next, Shankar decided to wind up not one but all shows produced by Balaji Telefilms that were running on its channel (in August 2015, Star even sold the 25.99 percent stake it held in Balaji Telefilms).

Joint ventures, like the one in sports broadcasting with ESPN, were ended too. This, Shankar says, gave Star the flexibility to target cricket broadcasting more aggressively and look at new sports such as hockey and kabaddi. Not only is Star a sports broadcaster at present, it also owns leagues such as the Pro Kabaddi League and has an equity interest in the Indian Super League (ISL) of football. “We have been able to do all this because we have no joint venture partner with whose expectations we have to align ourselves,” says Shankar.

Star also exited the news business, which Shankar had nurtured and which was, in many ways, responsible for getting him the top job. Star felt that as a minority shareholder in the venture, and with government regulations governing news broadcast being prohibitive, it wasn’t able to do much to act as a change agent in the business. Similarly, Star also exited its investment in cable TV and broadband service provider Hathway Cable & Datacom, where it was, again, a minority shareholder.

But what Star lost on account of the cords cut, it made up through innovative programming and by penetrating deeper into India’s regional entertainment markets that were growing in importance. These were regions in which Star had no presence, as it had built its network to predominantly cater to viewers in the country’s Hindi-speaking belt, including the two largest metros of Delhi and Mumbai. Under Shankar, Star expanded its geographical reach across India with the launch of channels like Star Jalsha in West Bengal, Star Pravah in Maharashtra, and the acquisitions of Asianet and Maa TV to strengthen its foothold in India’s southern states.

New shows like Satyamev Jayate were conceptualised. The show, hosted by actor Aamir Khan, discussed and provided possible solutions to address social issues in India. And it was a risky proposition: With an expensive celebrity like Khan hosting the show and extensive need for on-ground research that the format demanded, it was one of the most expensive shows to be produced on Indian television. Also, it aired on Sunday mornings and sceptics felt that grim tales of social ills may not sit well with viewers. But in terms of advertiser interest as well as viewership, Star proved that these fears were unfounded.

The other element of Shankar’s strategy was to make Star look and feel more Indian. Take marketing campaigns like ‘Rishta Wahi Soch Nayi’ and ‘Inspiring a Billion Imaginations’, which have connected with its audiences.

While Shankar has spent the last eight years bringing Star back on track as the leading broadcast network in India, his next mandate is to make the company future-ready. Investments in new businesses like its latest digital entertainment platform Hotstar and a focussed strategy to grow the sports business are part of the plan.

By innovating on technology and offering a wide bouquet of content to viewers, Hotstar has arguably become the next big thing on the Indian digital entertainment landscape after YouTube. Sample this: Since its launch in February 2015, Hotstar’s mobile app has witnessed 32 million downloads, according to the company. Its monthly reach averages 20 million unique users, and the average time spent by a user on Hotstar is 35 minutes per day. This makes Hotstar a compelling proposition for media buyers and advertisers looking to reach their target audience over a digital platform. Already, the universe of companies that is advertising through Hotstar boasts of names like Jaguar Land Rover, Nissan, ITC, Marico, Nestle, Coca-Cola, Colgate, Airtel, Idea Cellular, ICICI Prudential, Visa, Flipkart and Snapdeal.

Technologically, Hotstar promises users a better viewing experience by ensuring that videos can stream seamlessly even at low bandwidths. Content-wise, Hotstar streams live sporting events including cricket matches from the Indian Premier League (IPL) and international fixtures played in India as Star acquired the digital rights for these from the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) in 2012 (and for the IPL in 2014). It also streams live matches from multiple sporting leagues in India such as Pro Kabaddi, ISL, Hockey India League, and a tennis and badminton league each. It also features movies and television dramas that are a part of Star’s library of content.

In some aspects, Star is following a digital-first approach. For instance, many of the films for which Star has acquired cable, satellite and digital rights are being aired on Hotstar first and then on the TV channels, so as to drive viewership on the digital platform. It is also creating exclusive long-form content for Hotstar by tying up with content creators like comedy group AIB and Malishka, a popular radio jockey with 93.5 RED FM. This is a reversal of the trend in digital entertainment witnessed in India where content makes its way from TV and movie screens to mobile screens.

There were two immediate triggers for launching Hotstar, says Shankar: A growing trend of content being consumed online in India and the need to make full use of the digital rights that Star had acquired from BCCI for cricket matches featuring India. For the latter, Star is paying as much as Rs 2 crore per match to India’s apex cricket body. While the initial response to Hotstar has been encouraging, its future potential will depend on the quality and cost of bandwidth becoming optimal in India. If there is improvement on these parameters and 4G broadband gains traction then Hotstar may break even in two to three years, Shankar says.

Ajit Mohan, head of digital at Star India, says that Shankar is one of the best non-linear thinkers that he has come across. “Leaders tend to be intellectually and analytically strong but Uday connects the dots in the most non-linear fashion and comes up with insights that haven’t been articulated before,” says Mohan, who used to run the CEO’s office at Star and has worked closely with Shankar before being put in charge of Hotstar and Star’s other digital properties.

Srinivas of GroupM points out that Hotstar was one of the most successful digital brand launches that India has ever seen. “It gets a lot of traction when there is a live sporting event on. But it has still some distance to go before it becomes a regular channel for repeat content. That concept is yet to pick up, though it will in the future,” Srinivas says.

As is evident, Hotstar is intricately linked with Star’s sports business in India. And like it is true for 21st Century Fox around the globe, sports is a cornerstone for the broadcaster’s network in India as well. This explains why James Murdoch is supporting Shankar’s decision to create a larger footprint in the sports broadcasting business in India, even if it means investing in sporting leagues themselves; this is unprecedented for 21st Century Fox.

Like it was with Satyamev Jayate, Star’s decision to commit top dollars to developing kabaddi in the country was a bold and risky bet. There is no history of the sport enjoying much airtime or viewership on television in the past. Yet Shankar was convinced kabaddi had a market if it was packaged and positioned properly. “It struck me that a country as large and diverse as India cannot have just one sport —cricket,” Shankar says. “Kabaddi was a sport that all Indians were familiar with, but it was languishing due to lack of institutional support.”

Though it was a challenge selling kabaddi to advertisers in the first year since it was an unknown commodity, Shankar is happy with the response that the Pro Kabaddi League has received in the second year. In terms of viewership, the bet appears to have paid off for sure. It is only second to the hugely popular and established IPL. The 2015 season registered a growth of around 46.6 percent in television rating over the previous year. Additionally, 2.6 crore viewers watched the kabaddi matches on Hotstar, compared to only seven lakh viewers in 2014.

Shankar’s boss is clearly pleased with what he has achieved over the last eight years. James Murdoch told Forbes India in an email that “[he was] proud of what Star has accomplished over nearly a decade under the extraordinary leadership of [his] close colleague and friend [Shankar]”. Shankar is driven by a fundamental belief in the power of great storytelling as well as in the central role media can play in a dynamic and pluralistic society like India, adds Murdoch. “He brings to his role the deep curiosity and incisiveness of the best journalists but matched by an action-oriented style and a restless sense of pace in seizing opportunities,” he says.

This explains why he doesn’t need a chair. Why does he need to sit when he is always on the move?

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)