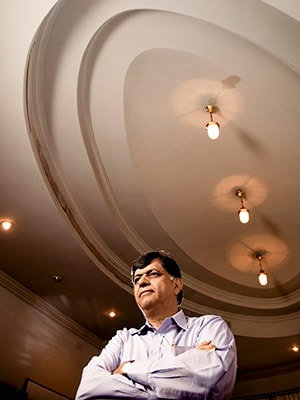

Vinod Ramnani: Time to Grow Opto Circuits Organically

After an acquisition binge, Opto Circuits’ Vinod Ramnani is looking to grow from within

Award: NextGen Entrepreneur for the Year

Name: Vinod Ramnani, CMD, Opto Circuits

Age: 56

Why He Won: For methodically moving up the value chain from non-invasive medical products to high-tech branded devices. For building a research-driven cross-border organisation.

“In three years, we want to be $1 billion [Rs 5,400 crore] in revenue,” says Valiveti Bhaskar, CFO, Opto Circuits. From its current revenues of nearly $440 million (about Rs 2,376 crore), that implies a growth of over 2.2 times.

A stretch target like that would have been eminently possible in the past for Vinod Ramnani, 56, the canny, reticent and measured co-founder and CMD of Opto Circuits.

After a modest IPO in 2000 for the company he started in 1992, Ramnani spent the next 10 years slowly but surely taking it from being just an unknown OEM (original equipment manufacturer) supplier of pulse oximeters—external medical devices that measure oxygen levels in the blood—to something much bigger. “He has the equal ability to spot timely opportunities or pass up on hyped trends,” says a financier who has worked with Ramnani for well over a decade now.

From 2001, Ramnani started acquiring companies, starting small and in India, before acquiring those in Europe and the US for much larger sums. By 2010, he had turned the Bangalore-headquartered Opto Circuits into a fairly formidable healthcare products company on the back of 10 acquisitions. From relatively simpler products, like patient monitors, Ramnani moved Opto Circuits up the value chain to stents, ECG machines and defibrillators. Each of the acquired companies was solid and profitable, throwing out predictable cash flows in short order. None were flashy or hyped up.

India, meanwhile, would serve as the base for low-cost manufacturing and access to capital. To keep investors happy, Ramnani announced bonus share offers almost every year. For instance, a single Opto Circuits share from 2002 would be 17 today.

At the same time, he also returned to the same investors much of the cash generated from his operations every year as dividend. The amounts weren’t small, with payouts ranging from 30-40 percent. It is only in recent years that it came down, falling to 14.9 percent in 2012.

But since early this year, Opto Circuits, which remained the perennial stock market darling for most of its listed life, fell out of favour with investors. Its stock was down 34 percent since April compared to the 6.5 percent that the BSE Sensex gained.

After a debt-fuelled, decade-long acquisition binge, investors now want Ramnani to take it easy. And Ramnani, who hasn’t made an acquisition since 2010, isn’t in any hurry. “We have stopped looking at acquisitions. We have to digest the ones we’ve already done.”

The next phase of Opto Circuits’ growth will have to come from within. Organically.

Organic Is in Fashion

“Our portfolio is now broad enough to support significant organic growth, which is why we now want to maximise returns through organic growth,” says Thomas Dietiker, a co-founder and promoter of Opto Circuits.

With further debt and acquisitions off the table for the next couple of years, Ramnani is adopting a dual-pronged strategy of organic growth and cost-cutting to remain in the good books of his investors. “We want each of our group companies to introduce at least one new product every year,” says Jayesh Patel, also a co-founder and promoter.

Many of the new products are being created or targeted specifically at countries like India, China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Brazil and a few from Africa. “In the US, clinical trials and [FDA] approvals can take a lot of time. So our focus will be on the European, Asian and Latin-American markets instead, where just a ‘CE approval’ [the European quality control mark] is enough,” says Ramnani.

Take Cardiac Sciences, Opto Circuits’ last major acquisition in 2010. Its leading product, the automatic external defibrillator (AED, a portable device that administers electric shocks to a patient undergoing a cardiac arrest) though popular in the US, is virtually unknown in markets like India. Opto Circuits is spending money in these countries, trying to create awareness of the product and its need in hospitals and public places like airports.

Ramnani hopes to repeat the success of Criticare, a manufacturer of patient monitoring systems acquired by Opto Circuits in 2008. Since then, its sales in India have gone up from $0.5 million (Rs 2.71 crore) to well over $4 million (Rs 21.7 crore) annually. “As more governments in Western markets continue to cut costs, we’re balancing that with emerging markets where more hospitals are still being built,” says Patel.

But, in order to do that, he has to make sure that scattered sales forces across countries are able to sell all his products. “We didn’t have proper marketing or sales channels earlier. With the acquisitions we have those now; we now want to sell more products through them,” says Ramnani.

So the company’s sales forces, hitherto isolated within the acquired companies, have been unified into a single force that has been trained over the last year to use and sell most of its products.

The long learning curve involves pairing a salesperson selling a peripheral artery disease (PAD) monitoring device but with no clue on how to sell an ECG with another employee who does. The team does demos and sales calls together. “The biggest challenges are egos, because some of the people have been selling for 20 years,” says Patel.

The other equally important aspect is reducing costs. “For companies in our space in the US, a 50 percent gross margin often translates to a 5 percent profit margin. This is due to the high cost of sales, marketing and manufacturing. All of those can be controlled without affecting the quality of a product,” says Bhaskar.

New products for emerging markets are being developed and manufactured from India and Asia. Ramnani says he has tripled his R&D team in Bangalore to 75 during the last year alone. As a result, Opto Circuits is today doing both “maintenance”, “sustenance” and “upgradation” R&D from India instead of the US for most of its products.

The cost of new products is also being brought down by reengineering them to suit the needs of emerging markets and regulatory environments. Non-critical manufacturing activities, like cable harnessing, are being done in India at 10-20 percent of the cost in the US.

At the management level, the company now has one CEO each for its invasive and non-invasive international businesses, instead of having one for each company in its fold. All the marketing layers have been “collapsed to just one”, says Ramnani. All departments have been given cost-cutting targets ranging from 7-10 percent, with the exception of sales and marketing. “We have realised cost savings of 5-7 percent in our raw materials alone because of bundling,” says Ramnani.

In September 2009, when I had met him for an interview, he told me, “There are no acquisitions on the horizon for us, though in business you cannot say yes or no to anything forever.” The very next year he went on to do three acquisitions, spending over a quarter of his company’s $245 million (about Rs 1,323 crore) annual revenue in the process. This time round, Ramnani may just have to go slow.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)