The 10 big questions for 2019 - Part 1

Here's a look at the most important issues plaguing different sectors in the country, and the possible scenarios that may play out in the coming year

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock1. Will the foreign investor return?

Although spooked foreign investors put some distance between themselves and Indian equities in 2018, things might change for the better in the New Year.

In 2018, the BSE Sensex and the Nifty 50 have gained just 3.4 percent and 1.06 percent respectively, with foreign investors being net sellers in Indian equities. The net sell figure for 2018 stood at ₹71,700 crore.

Part of the sell-off was due to the Securities and Exchange Board of India taking steps to stop the misuse of participatory notes by registered foreign portfolio investors, unless they disclosed the identity of the investor; this impacted their investments in India. Also, a depreciating rupee and the risk of fiscal slippage on account of high oil prices made them circumspect for most of the year’s second half.

Moving into 2019, a lot of the uncertainty begins to dissipate, because of two factors: Emerging markets, which had underperformed the developed markets in 2018, are likely to be favoured in 2019 because of reasonable valuations and the growth differential; also, the US economy—which witnessed an upswing as funds were ploughed money back from emerging markets to the US—might just start to slow down.

For India, a stable rupee, benign inflation and possibly lower rates remove the risk of a large market sell-off. (A global sell-off would, however, mean all bets are off).

Apart from this macro-economic positive, India could witness a corporate earnings expansion of around 15 percent by FY20 after five years of subdued earnings growth. That’s something well worth buying into.

—Salil Panchal

Although spooked foreign investors put some distance between themselves and Indian equities in 2018, things might change for the better in the New Year.

In 2018, the BSE Sensex and the Nifty 50 have gained just 3.4 percent and 1.06 percent respectively, with foreign investors being net sellers in Indian equities. The net sell figure for 2018 stood at ₹71,700 crore.

Part of the sell-off was due to the Securities and Exchange Board of India taking steps to stop the misuse of participatory notes by registered foreign portfolio investors, unless they disclosed the identity of the investor; this impacted their investments in India. Also, a depreciating rupee and the risk of fiscal slippage on account of high oil prices made them circumspect for most of the year’s second half.

Moving into 2019, a lot of the uncertainty begins to dissipate, because of two factors: Emerging markets, which had underperformed the developed markets in 2018, are likely to be favoured in 2019 because of reasonable valuations and the growth differential; also, the US economy—which witnessed an upswing as funds were ploughed money back from emerging markets to the US—might just start to slow down.

For India, a stable rupee, benign inflation and possibly lower rates remove the risk of a large market sell-off. (A global sell-off would, however, mean all bets are off).

Apart from this macro-economic positive, India could witness a corporate earnings expansion of around 15 percent by FY20 after five years of subdued earnings growth. That’s something well worth buying into.

—Salil Panchal

2. Will startup funding become harder?

Indian startups in their infancy may struggle to find a financial backer, but once they do, and prove the worth of their business, they are likely to find investors queuing up. “The quality of companies in this cycle is definitely better than those in say circa 2015,” says Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder at IndigoEdge, an investment bank.

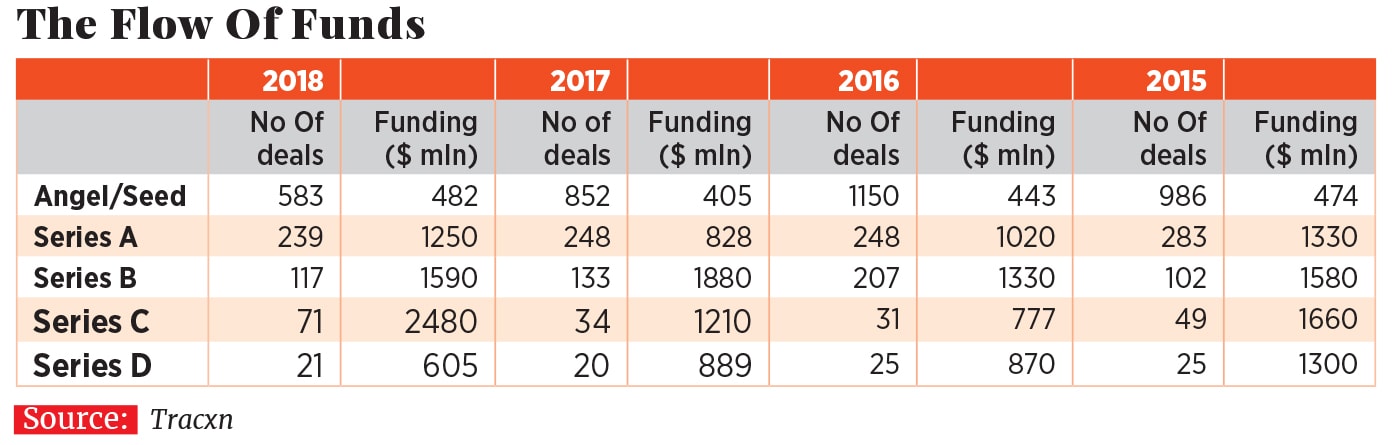

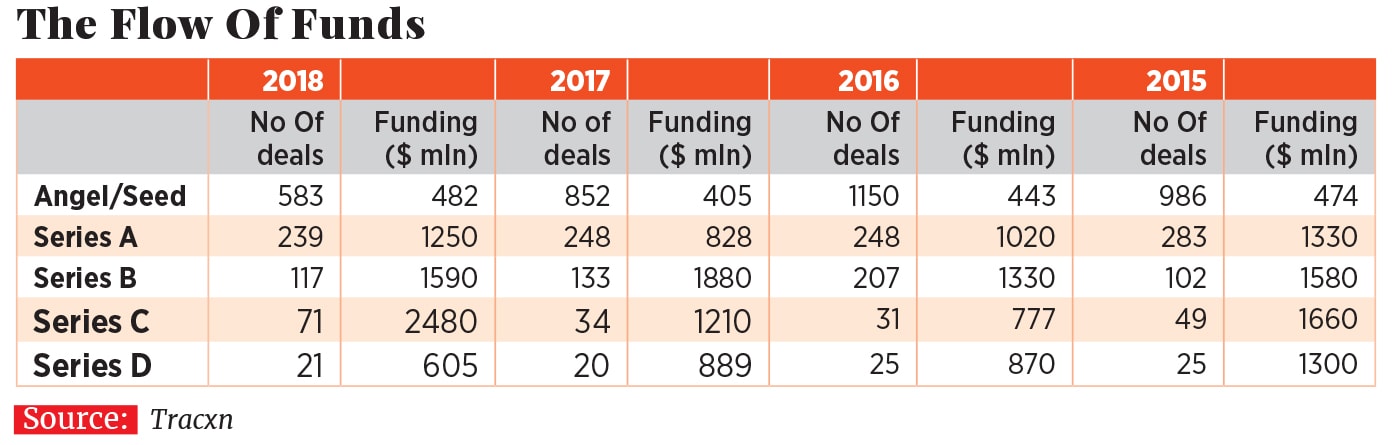

According to Tracxn, the number of early-stage deals shrunk significantly—from 986 to 583—between 2015 and December 21, 2018. However, the money invested remains almost the same—$474 million in 2015, compared to $482 million in 2018—which implies that while investors are backing fewer startups, they are pumping more money than before in the ones they pick. This is in stark contrast to the bursting of the funding bubble in 2015, when all startups were impacted irrespective of the quality of their business.

Indian startups in their infancy may struggle to find a financial backer, but once they do, and prove the worth of their business, they are likely to find investors queuing up. “The quality of companies in this cycle is definitely better than those in say circa 2015,” says Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder at IndigoEdge, an investment bank.

According to Tracxn, the number of early-stage deals shrunk significantly—from 986 to 583—between 2015 and December 21, 2018. However, the money invested remains almost the same—$474 million in 2015, compared to $482 million in 2018—which implies that while investors are backing fewer startups, they are pumping more money than before in the ones they pick. This is in stark contrast to the bursting of the funding bubble in 2015, when all startups were impacted irrespective of the quality of their business.

Funds for the right startups may not be a constraint, especially with most of the top investors—Sequoia Capital, SAIF Partners, Matrix Partners, Nexus Venture Partners, Chiratae Ventures, Saama Capital, Fireside Ventures, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Inventus Capital India, Stellaris Venture Partners and Lightbox—having raised fresh capital in the last 12 to 15 months. Besides, there is the emergence of venture debt—from the likes of InnoVen Capital, Algeria Capital and Trifecta—for those entrepreneurs who don’t want to dilute their stake.

Growth capital of a couple of hundred million dollars, which would have otherwise prodded startups to cut losses and contemplate a public offering, is more readily available. IPOs can wait, with global investors such as SoftBank, Tencent, Naspers and Alibaba emerging as a source of large cheques to the sectoral winners.

“Certain verticals, or certain type of businesses, will get funded more. In segments such as food or travel, only the leaders will get funded. But, what you will continue to see is more consortium funding, where two or three investors come together to back a particular company, instead of each one them trying to fund one company in a hot sector,” adds Ramaswami.

—Sayan Chakraborty

Growth capital of a couple of hundred million dollars, which would have otherwise prodded startups to cut losses and contemplate a public offering, is more readily available. IPOs can wait, with global investors such as SoftBank, Tencent, Naspers and Alibaba emerging as a source of large cheques to the sectoral winners.

“Certain verticals, or certain type of businesses, will get funded more. In segments such as food or travel, only the leaders will get funded. But, what you will continue to see is more consortium funding, where two or three investors come together to back a particular company, instead of each one them trying to fund one company in a hot sector,” adds Ramaswami.

—Sayan Chakraborty

3. Will bank NPAs start falling?

Image: Danish Siddiqui/ Reuters

Image: Danish Siddiqui/ Reuters

Finally, the worst appears to be over for Indian banks, though there could be some more pain till March 2019. After years of aggressive recognition, gross non-performing assets (NPAs), plus restructured standard advances, in the banking system remained high at 12.1 percent (₹10.3 lakh crore) of gross advances, as of March 2018, compared to 9.5 percent for FY17. But a mix of lower slippages and higher provisioning for NPAs is starting to reflect in the books of some of the larger banks. Therefore, a fall in NPAs can be expected.

Gross bad loans, as a percentage of gross advances, for some of India’s biggest public sector banks (State Bank of India and Bank of Baroda) and private sector banks (HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank) have fallen in the September-ended quarter, compared to the June-ended quarter. For a lot of these banks, the leadership has started to understand that it is better to deal with the pain upfront even if it comes at the expense of profitability.

“We are seeing a moderation in slippages, and we do expect NPA levels to drop in the next fiscal,” says Mahantesh Sabarad, head of research at SBI Cap Securities. Besides, credit growth is starting to pick up, which will also result in a fall in NPA ratios.

Recovery of unpaid corporate loans, through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, has improved, but is still slow. About ₹80,000 crore was recovered in 2018, from debtors who had defaulted earlier, according to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs. Most of this has been due to the sale of steel assets, such as Essar Steel and Bhushan Steel. The money is likely to be reflected in bank balance sheets in 2019. For other bankruptcies, the banks will likely write off the loans, enabling them to lend again.

—Salil Panchal

4. Will Indian exports outperform?

Image: Amit Dave/ Reuters

Image: Amit Dave/ Reuters

Since 2014, indian exports have suffered a lost half-decade, and it’s unlikely that 2019 can meaningfully increase their tepid rate of growth. Subdued oil prices and a weakening world economy paint a dismal prospect for Indian exports, which have been stuck in the $250-300 billion range since 2013.

Queering the pitch further is the unknown impact of the trade war between the United States and China. Companies are unsure about the impact on supply chains and, for now, have adopted a wait-and-watch approach. The small shifts in production that have taken place have benefited Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines, at the expense of India.

“A lot of how we perform depends on the state of the world economy,” says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings. He points to the fact that even at times when the world economy witnessed a synchronised upswing, like in 2017, Indian exports still underperformed. “The world economy doing well is a necessary condition, but not the only one,” he says.

Petroleum exports, priced in dollars and making up a third of India’s exports, are likely to drag growth in 2019 on account of low oil prices. Slowing growth in Europe and the US mean that engineering exports are also likely to be impacted. One bright spot is chemicals, which has been growing at double digit rates in the last five years and now makes up a third of exports. Textiles faces increased competition from Southeast Asia and Turkey.

For now the government has its hopes riding on the rupee depreciation. An 8 percent depreciation in the rupee in 2017 is seen as adding a tailwind to exports. However, data from past depreciation cycles shows that customers quickly ask exporters to give them the benefit of lower dollar prices. At best it may act as a short-term boost to margins.

—Samar Srivastava

5. Will consumer prices remain below 4 percent?

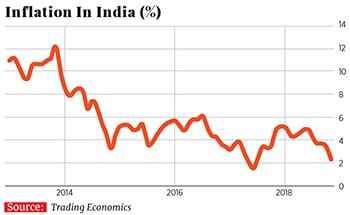

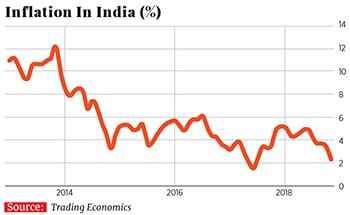

Retail inflation has been falling in both urban and rural India, and stood at a 17-month low of 2.3 percent in November 2018. This good news is unlikely to sustain in 2019. Experts believe that retail inflation will start seeing an uptick in 2019.

The fall in consumer price inflation (CPI) has been due to lower food prices. Fuel, which makes up 6.8 percent of the CPI basket, has remained benign this year. Oil’s spike to above $80 a barrel proved short-lived. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has a medium-term CPI target of 4 percent with room for a 2 percent deviation.

The fall in consumer price inflation (CPI) has been due to lower food prices. Fuel, which makes up 6.8 percent of the CPI basket, has remained benign this year. Oil’s spike to above $80 a barrel proved short-lived. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has a medium-term CPI target of 4 percent with room for a 2 percent deviation.

India has witnessed two normal monsoons (2016 and 2017) and a near-normal one in 2018. The possibility of an El Nino event in early 2019 is likely to have an impact on monsoon in 2019. This, coupled with the base effect of 2018, could mean that the CPI in 2019 will remain high, compared to 2018.

A key reason for CPI’s fall so far may also prove to be its undoing. An election year could see significant hikes in the minimum support prices (MSPs) for a host of agri-commodities.

“CPI inflation will continue to inch up to around 5.5 percent by end of 2019, led by higher vegetable prices,” says Dhananjay Sinha, head of institutional equities, Emkay Global Financial Services. “As the farm sector remains under stress, it is imperative that future governments continue to focus on increasing the MSP.”

The ruling government—and the new government post May 2019—is likely to overhaul the existing system to increase incomes for small and marginal farmers. This could be through input price support or through higher MSPs. This will also impact food prices and future CPI trends.

Do not expect galloping inflation rates either. Moderate oil prices, a stable rupee and muted Indian growth will likely keep it in check.

—Salil Panchal

Image: Danish Siddiqui/ Reuters

Image: Danish Siddiqui/ Reuters Finally, the worst appears to be over for Indian banks, though there could be some more pain till March 2019. After years of aggressive recognition, gross non-performing assets (NPAs), plus restructured standard advances, in the banking system remained high at 12.1 percent (₹10.3 lakh crore) of gross advances, as of March 2018, compared to 9.5 percent for FY17. But a mix of lower slippages and higher provisioning for NPAs is starting to reflect in the books of some of the larger banks. Therefore, a fall in NPAs can be expected.

Gross bad loans, as a percentage of gross advances, for some of India’s biggest public sector banks (State Bank of India and Bank of Baroda) and private sector banks (HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank) have fallen in the September-ended quarter, compared to the June-ended quarter. For a lot of these banks, the leadership has started to understand that it is better to deal with the pain upfront even if it comes at the expense of profitability.

“We are seeing a moderation in slippages, and we do expect NPA levels to drop in the next fiscal,” says Mahantesh Sabarad, head of research at SBI Cap Securities. Besides, credit growth is starting to pick up, which will also result in a fall in NPA ratios.

Recovery of unpaid corporate loans, through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, has improved, but is still slow. About ₹80,000 crore was recovered in 2018, from debtors who had defaulted earlier, according to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs. Most of this has been due to the sale of steel assets, such as Essar Steel and Bhushan Steel. The money is likely to be reflected in bank balance sheets in 2019. For other bankruptcies, the banks will likely write off the loans, enabling them to lend again.

—Salil Panchal

4. Will Indian exports outperform?

Image: Amit Dave/ Reuters

Image: Amit Dave/ Reuters Since 2014, indian exports have suffered a lost half-decade, and it’s unlikely that 2019 can meaningfully increase their tepid rate of growth. Subdued oil prices and a weakening world economy paint a dismal prospect for Indian exports, which have been stuck in the $250-300 billion range since 2013.

Queering the pitch further is the unknown impact of the trade war between the United States and China. Companies are unsure about the impact on supply chains and, for now, have adopted a wait-and-watch approach. The small shifts in production that have taken place have benefited Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines, at the expense of India.

“A lot of how we perform depends on the state of the world economy,” says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings. He points to the fact that even at times when the world economy witnessed a synchronised upswing, like in 2017, Indian exports still underperformed. “The world economy doing well is a necessary condition, but not the only one,” he says.

Petroleum exports, priced in dollars and making up a third of India’s exports, are likely to drag growth in 2019 on account of low oil prices. Slowing growth in Europe and the US mean that engineering exports are also likely to be impacted. One bright spot is chemicals, which has been growing at double digit rates in the last five years and now makes up a third of exports. Textiles faces increased competition from Southeast Asia and Turkey.

For now the government has its hopes riding on the rupee depreciation. An 8 percent depreciation in the rupee in 2017 is seen as adding a tailwind to exports. However, data from past depreciation cycles shows that customers quickly ask exporters to give them the benefit of lower dollar prices. At best it may act as a short-term boost to margins.

—Samar Srivastava

5. Will consumer prices remain below 4 percent?

Retail inflation has been falling in both urban and rural India, and stood at a 17-month low of 2.3 percent in November 2018. This good news is unlikely to sustain in 2019. Experts believe that retail inflation will start seeing an uptick in 2019.

India has witnessed two normal monsoons (2016 and 2017) and a near-normal one in 2018. The possibility of an El Nino event in early 2019 is likely to have an impact on monsoon in 2019. This, coupled with the base effect of 2018, could mean that the CPI in 2019 will remain high, compared to 2018.

A key reason for CPI’s fall so far may also prove to be its undoing. An election year could see significant hikes in the minimum support prices (MSPs) for a host of agri-commodities.

“CPI inflation will continue to inch up to around 5.5 percent by end of 2019, led by higher vegetable prices,” says Dhananjay Sinha, head of institutional equities, Emkay Global Financial Services. “As the farm sector remains under stress, it is imperative that future governments continue to focus on increasing the MSP.”

The ruling government—and the new government post May 2019—is likely to overhaul the existing system to increase incomes for small and marginal farmers. This could be through input price support or through higher MSPs. This will also impact food prices and future CPI trends.

Do not expect galloping inflation rates either. Moderate oil prices, a stable rupee and muted Indian growth will likely keep it in check.

—Salil Panchal

X