Tatas gamble in a bloodied aviation market

Even as IndiGo, Jet Airways and SpiceJet report combined losses of ₹2,300 crore in the September quarter, the $100-billion Tata group is eyeing a larger play in India's aviation sector

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

In December 2012, as the outgoing chairman of Tata Sons, industrialist Ratan Tata, who nursed dreams of operating an airline and even an airport in Bengaluru, seemed to have given up on his plans. “It [the aviation sector] is somewhat like telecom. It is proliferated by many operators, some of them in financial trouble,” the Press Trust of India quoted Tata as saying. “I would hesitate to go into the sector today in the sense that the chances are that you would have a great deal of competition which would be unhealthy competition.”

Tata’s uncle, JRD Tata, had founded Tata Airlines in 1932; it is now Air India, an entity owned by the government of India.

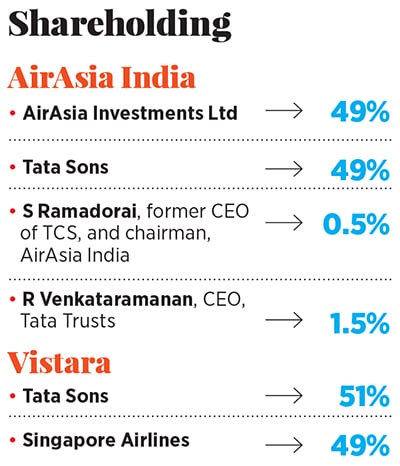

Six months after that statement, Tata Sons, the holding company of the over-$100 billion Tata group, entered the Indian skies with two joint venture partnerships in AirAsia India, with Malaysian budget airline AirAsia, and Vistara, a tie-up with Singapore’s flag carrier Singapore Airlines.

Ironically, in the last six years, nothing has changed with regard to the state of the Indian aviation sector, especially the way Ratan Tata perceived it to be, as well as Tata Sons’ unabated interest in the space.

According to media reports, Tata Sons is in talks to acquire the financially distressed full-service airline Jet Airways. “We do not comment on market speculation,” a Tata Sons spokesperson told Forbes India. Jet Airways has informed the Indian bourses that the news items are “speculative in nature”. And if at all a deal does conclude, it may be some time away; it could even fall through at any stage of the negotiations.

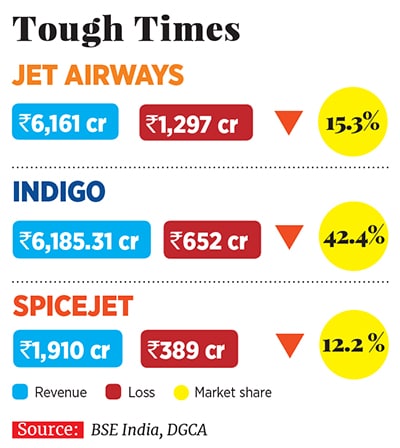

Presently, competition is fierce and the aviation industry is bleeding red—the combined losses of IndiGo, Jet Airways, and SpiceJet, which together control 70 percent of the market, in the July to September quarter of FY19 total ₹2,300 crore. Unlike the other two airlines, Jet Airways reported a loss for the third consecutive quarter; its cumulative losses since March 2018 are more than ₹3,650 crore.

An over-50 percent surge in fuel costs combined with the rupee depreciation and low air fares are hurting the fortunes of Indian airlines. Air travellers though aren’t complaining, as there has been a 20 percent growth in domestic traffic.

Jet Airways is the second largest airline with a 15.3 percent market share and, more importantly, over 50 percent of its revenue comes from international flights. “Jet Airways, with all its international flying rights, is an established airline. It will complete the portfolio for the Tatas who have been interested in aviation [since the 1930s],” says independent research analyst Sanjay Jain.

Tata Sons has been either a significant minority shareholder (it initially held a 30 percent stake which was upped to 49 percent in AirAsia India) or majority shareholder (51 percent in the case of Vistara), but not the actual operator of the airlines.

Given the Tata group’s vast consumer connect, the Tata brand, says Jain, “enjoys a lot of public trust”. “Aviation is a B2C (business-to-consumer) business and the Tatas really understand that,” he points out.

But would it understand the mind of a self-made, belligerent market leader like IndiGo? For one, IndiGo does not seem to be weighed down by prevailing market conditions. Even though fuel prices were responsible for more than half of its profit decline, IndiGo added five new destinations and 35 new routes in the July to September period. Its management has announced a further 35 percent increase in capacity in the October to December quarter. Reason: It has over `13,000 crore in cash reserves.

“Aviation requires deep pockets in order to withstand the irregularities in fuel prices. In Tatas, you get a deep-pocketed, long-term committed aviation investor, which the country always lacked,” says Jain. One could argue that the Indian taxpayer has been the most committed long-term aviation investor by keeping Air India, which has debt overhang of ₹48,000 crore, afloat all these years.

There would indeed be questions over Tata’s capital commitment to the aviation sector as the Tata group, which comprises more than 100 companies, is going through a portfolio churn at this point. In fact, they might need to relook at their existing aviation joint ventures—AirAsia India hasn’t made any significant dent in the Indian market.

If Tata Sons ends up buying Jet Airways, a possible merger between Vistara and Jet Airways could be on the cards. Both are full-service airlines and Jet Airways’ international routes would give Vistara a quick backdoor entry into key markets in Europe and West Asia. Also, Jet Airways’ domestic route network would boost Vistara’s presence in key metro markets.

Besides, history shows that airline mergers in India, whether it is Air India and Indian Airlines, Jet Airways and Air Sahara, or Kingfisher Airlines and Air Deccan, have been a disaster. “A lot of what is happening to Jet Airways [its financial troubles] is because it hasn’t been able to successfully close out the [Air] Sahara merger,” Ajay Awtaney, editor, livefromalounge.com, a business travel website, had told Forbes India in a previous interview.

That said, Tata Sons buying Jet Airways, says Jain, would be good for the Tatas and the owners of Jet Airways. “And I think over and above that, it’s going to be good for the aviation industry, as the Tatas represent long-term commitment.”