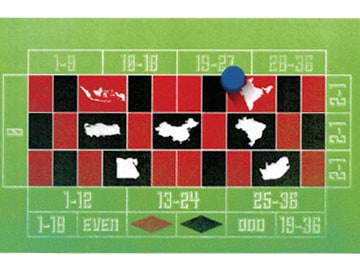

Great Potential. Great Peril.

Required – a roadmap for risk when investing in emerging markets

Emerging markets hold the potential for extraordinary growth, but they contain risks not present in the developed world. Quantifying that risk becomes all the more important to fi rms and portfolio investors as they increasingly look toward the emerging markets, where the most exciting growth opportunities reside.

Finance professor Christian Lundblad emphasizes the importance of accurate risk measures when making corporate or portfolio investment decisions in emerging markets. Overestimate risk and you might miss out on great returns. Underestimate it and you might be in for an ugly surprise.

Lundblad develops a technique to isolate the premium charged for political risk by using information in the relative market yields of sovereign debt. He explains in his paper “Political Risk and International Valuation” with Geert Bekaert of Columbia University, Campbell R. Harvey of Duke University and Stephan Siegel of the University of Washington.

“Looking at the difference between what a borrowing country pays its creditors in U.S. dollars and the interest rate the U.S. Treasury pays over a similar term tells us something about what the market is thinking about that country’s ability to repay its debt and all the challenges that country is facing,” Lundblad said.

For instance, if the Peruvian government wants to borrow U.S. dollars (a likely scenario, because an emerging country wants to attract foreign capital, and lenders are more comfortable lending in their own currency), global creditors will charge the Peruvian government a higher interest rate, presumably, than it would charge the U.S. government (generally perceived to be credit risk-free, recent developments notwithstanding).

A multinational corporation (MNC) investing in an emerging market needs to take into account not only the normal business risks associated with its operations but also risks specific to that country. For example, when an MNC active in China makes investment decisions, it has to factor in the likelihood of corruption, regulatory discrimination that favors local competitors and potential difficulties in repatriating gains. It also needs to consider unusual but important scenarios in which, say, the Chinese political structure is completely overturned.

The catchall term “political risk” reflects these and other related risks important for an MNC’s operations. Standard approaches used to quantify investment risks in developed countries don’t always reflect the factors that might be of first-order importance for an MNC in an emerging economy. Investors active in such markets have struggled to develop a method to assess risk, and, thus far, only ad hoc tools have been developed. Lundblad discovered that the ways firms quantify these risks vary dramatically from firm to firm.

“Some completely ignore it, which means that they are ignoring a serious risk consideration and potentially investing at levels they shouldn’t,” he said. “Some make adjustments that incorporate a composite of many different kinds of risk, some of which aren’t important to MNCs. They are overpenalizing projects and not investing in opportunities they should.”

Unfortunately, the sovereign debt spread, while useful, is determined by many other factors potentially unrelated to the risks that MNCs need to consider. For example, global credit conditions and the local bond-trading environment signifi cantly affect the spread. A spread elevated by a global credit crunch (like that witnessed in the fall of 2008) could incorrectly lead an MNC to adjust for a risk factor that has little to do with the political risk associated with the investment.

Instead, Lundblad created a method to isolate a political risk spread, stripped out from the sovereign spread. A more precise understanding of an investment’s risk, including political risk, reduces the likelihood that an MNC will misallocate capital.

To come up with this political risk spread, Lundblad and his colleagues first collected sovereign spread data for a wide range of emerging countries. They then gathered data on the potential determinants of the sovereign spread, including detailed data on political risk perceptions from the International Country Risk Guide. A statistical exploration then identifies the components of the spread.

Returning to the example of Peru borrowing U.S. dollars – if it cost Peru three percent more to borrow dollars than it cost the U.S. government, Lundblad’s method could determine how much of that extra three percent comes from things that MNCs should be concerned about and how much is attributable to other, unrelated, factors. Isolating the political risk spread might prevent the company from rejecting otherwise good projects. Investing too little not only hurts the MNC – preventing it from reaping good returns – but it does a disservice to the emerging market country by impeding foreign investment in its economy.

“This can matter a great deal for job creation, poverty reduction and economic growth in the emerging market, the recipient of the investment,” Lundblad said.

Lundblad, an expert in international finance and emerging markets, has won wide acclaim for his writings. His paper “Liquidity and Expected Returns: Lessons From Emerging Markets” provides a new measure of liquidity in emerging markets, which are notorious for their difficult trading environments. The data suggest that local market liquidity risk is an important driver of expected returns in emerging markets.

In another widely cited paper – “Does Financial Liberalization Spur Growth?” – Lundblad shows that equity market liberalizations (the regulatory process of opening up to foreign investors) lead to sizeable increases in local investment and economic growth. This issue had been hotly debated, with obvious and important policy implications for countries that might be actively considering opening their securities markets to outside investors.

Lundblad provides a real-time measure of equity market segmentation based on the magnitude of valuation differentials across markets for similar securities in “What Segments Equity Markets?” The new measure permits the exploration of the degree to which international markets have become more integrated, as well as a better understanding of the factors that impede further integration. While globalization has narrowed equity price differentials around the world, partial segmentation in emerging markets remains. Factors that make some countries more frightening from a business standpoint, including the political and institutional risks highlighted above, continue to effectively segment otherwise open markets.

Since the release of his paper on political risk and international valuation, Lundblad has delivered his fi ndings to researchers and central bank staff in Peru, India and the United Kingdom. He presented his research to the Bank of Italy last fall during the Italian government’s transition.

Lundblad’s research has implications for policy. Policymakers in the developing world use the sovereign spread to infer what market participants are thinking about their country’s prospects. Using Lundblad’s method, policymakers can focus on the most relevant components of the spread. To attract additional foreign they can better understand the risk charge for a potentially challenging institutional environment. Then perhaps they can guide reforms to enhance the perception of their country being business friendly.

“If foreign businesses aren’t investing,” Lundblad said, “that affects jobs and the economy in that country. It’s important to quantify the impediments.”

Lundblad already has begun thinking about how MNCs can structure their investments in such a way that they take advantage of the opportunities that emerging markets offer without overly exposing themselves.

“The question going forward is: How do we mitigate this risk?” he said. “In emerging markets, the risk is high, but so, too, is the expected return. Getting that ratio right is really important.”

Christian T. Lundblad is the Edward M. O'Herron Distinguished Scholar and an associate professor of finance at UNC Kenan-Flagler.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from research from the UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School: http://www.kenan-flagler.unc.edu/]