Moving from friction to cooperation, how better industry-university linkage can benefit academia

India can make the industry-academia relationship a focal point of developing our research acumen. We need to devote our energies towards converting conflict of interest to a confluence of interest as an ultimate solution

The most significant concern is the conflict between a university's need to protect the right to publish against the industry's need to protect patents and proprietary information

The most significant concern is the conflict between a university's need to protect the right to publish against the industry's need to protect patents and proprietary information

Image: Shutterstock

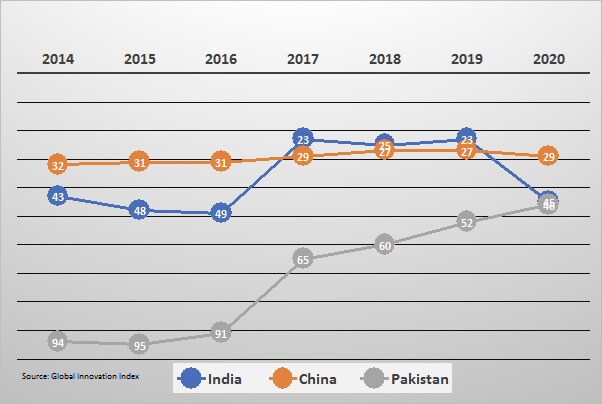

For many, it would be surprising to know that in the SCImago Country Rankings for scientific production, India ranks seventh globally with 2.1 million published documents and 22.2 million citations in 1996-20001. India also has the highest number of universities globally (4381 universities), ranks second globally in startups (10,757) and hosts more than 63 million Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. Yet, paradoxically, the country lags in University-Industry research collaboration. In the Global Innovation Index 2020 ranking for University/Industry Research Collaboration, India is placed 45th, at the same score as Pakistan, at 46th. Figure 1 shows the Indian ranking compared to China and Pakistan between the years 2014-2020.

Figure 1: Global Ranking in University/Industry Research Collaboration 2014-20

Why the paradox?

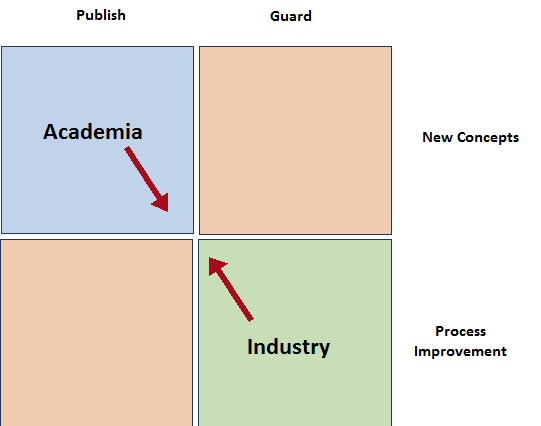

Fowler (1984), in his seminal work, has identified 15 impediments to university-industry relationships. The most significant concern is the conflict between a university's need to protect the right to publish against the industry's need to protect patents and proprietary information. The other significant cross purpose is that academics tend to concentrate on fundamental research that establishes new concepts. At the same time, the industry focuses on process improvement through applied research for short-term profits. To my mind, these are two wholly resolvable frictions behind the paradox.[This article has been reproduced with permission from the Indian School of Business, India]