Rajiv Shastri: Containing Subsidies Will Be a Must

While there are many causes for India’s current dismal economic state, the largest negative contributor is the manner in which its recent fiscal policy has evolved

Like every year, the end of 2013 provides an opportunity to reflect on what has transpired and what comes next. On the macroeconomic front, the most noteworthy development in 2013 was the elevated Current Account Deficit (CAD) in the first half of the year and its consequences in the second half. A lot of the narrative surrounding it has focussed on the Indian appetite for gold and its contribution to economic stress. Consequently, managing this appetite has been the focus of our remedial efforts as well. And while visible stress on the current account has reduced, without sustained initiatives to address the underlying causes, this is not a cure.

Since CAD is broadly equal to capital inflows, it can also be seen as the gap between domestic savings and investments.

Savings of all three sectors of the economy—government, corporations and households—have been under stress in recent years. While household savings and corporate profits have responded to economic realities like high inflation and slow growth, the evolution of government dissavings is alarming and worrisome.

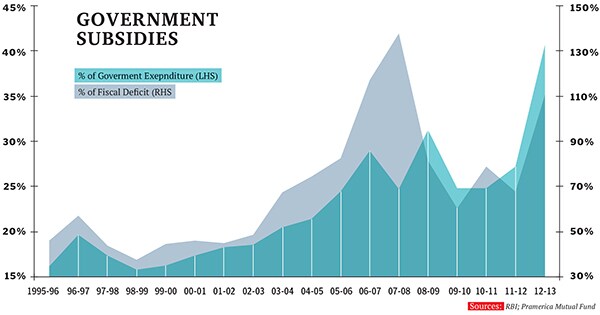

While there are many causes for India’s current dismal economic state, the largest negative contributor is the manner in which its recent fiscal policy has evolved. This does not refer to the deficit in isolation, but the basic structure of government expenses. A growing portion of government expenditure and GDP is now contributed by subsidies. This renders large portions of the economy commercially unviable for both private and public enterprise, and distorts the demand-supply equilibrium.

Since the link between these subsidies and economic growth is tenuous at best, government expenditure is increasingly driven by structural, rather than cyclical, factors. This makes the absolute amount sticky on the downside, increasing the possibility of deeper deficits in bad years and reducing the probability of surpluses in good ones. It also lays the foundation for elevated levels of inflation and higher interest rates which, in turn, may depress economic growth further and reinforce the cycle.

In addition, if the actual fiscal deficit remains elevated at a time when corporate profits and household savings are depressed or even stagnant, the only way to control CAD will be through lower investments, hurting future economic growth.

With subsidies accounting for more than 40 percent of government expenditure, 6.08 percent of GDP, and exceeding the fiscal deficit in FY2013, it is the single most important economic parameter to track in FY2014 and beyond. Numbers for the first quarter of FY2014 are not encouraging.

Even more worrying is the exclusion of pertinent data from the second quarter’s official release. This change in a data dissemination standard, which has existed for more than 15 years, induces questions on the reasons for exclusion, and fear that the data may have actually worsened significantly from already worrying levels.

With the FY2014 budget die already cast, any hope for the future will be based on the FY2015 budget. It is imperative that the government makes a serious attempt to contain subsidies, primarily inflationary subsidies that increase demand in the economy without changing the supply. Else, all that is gained through a possible global recovery will be lost in domestic transit.

The author’s views are personal

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)