Extreme poverty has gone down: Bill Gates

Bill Gates says India is the second biggest contributor to poverty reduction after China

Microsoft founder Bill Gates believes political will is essential to meet humanitarian goals

Microsoft founder Bill Gates believes political will is essential to meet humanitarian goals Image: Yana Paskova / Getty Images

On September 18, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation released its report card on the sustainable development goals (SDGs) for 2030 that the United Nations members adopted in 2015. In an exclusive interview with CNBC-TV18, Bill Gates talks about targets that are attainable, those that are aspirational, and the political risks that could come in the way of achieving them. Edited excerpts:

Q Let’s talk about the Goalkeepers report which you first published in 2017. In it you said there is more doubt than usual about the world’s commitment to development. Do you believe that there is less political will today to try and address the developmental needs of the world?

When you have a financial crisis (like in 2008) or the Syrian civil war with lots of refugees, the world is going to get fairly short-term as countries turn a bit inward when they are facing those challenges. The long-term issues of getting rid of extreme poverty, solving climate change, innovating, say for farmers, so that they can deal with new climate and still be themselves… can get squeezed away. So, yes, it is always a risk that countries are turning inward and certainly there are political leaders now who are more nationalistic than thinking about all of humanity.

Q Melinda Gates said the report was meant to be a wake-up call to leaders of certain countries. Has it got the attention of the leaders you were hoping to address?

I think it is impressive that the aid commitments have been maintained despite this wave of more inward-looking politics. The US maintained its aid levels, the UK was generous —all the way up to 0.7 percent (of gross national income). Germany’s aid budget has gone up, France is committed to increasing theirs.

Q You have spoken about how some SDGs are realistic and some aspirational. Which are the ones where you believe that the deficit between reality and aspiration has been bridged significantly?

Our foundation’s deepest expertise is in agricultural output and health. On the health side, we made sure that the objectives were ones that stood a chance of being achievable. The world has gotten so smart about these health things, new vaccines are being adopted, whether it is the pneumococcus vaccine or the rotavirus vaccine. In fact, India is now in the process of rolling that out over time to all the children there. Africa is getting close to achieving that goal. So health is where we are very deep into and it is primal. If you do not get the health of your kids right, then even if you send them to school, they are not fully developed mentally or physically to be able to benefit from that. So education and health are pretty special because that is the capital, that is your next generation. It only pays off over 20 years but it is the primary thing that predicts what will happen to your economy in that next generation.

India has done well on access, but when it comes to the amount of learning, it has a lot of room for improvement... it has fallen behind on the quality of its learning outcomes.

Q But do people get it because the concern is that when you invest in things like physical infrastructure, the results are perhaps quicker, more tangible as opposed to investing in education, knowledge and skills development which are the need of the hour?

Certainly there is nothing wrong with (investing in) infrastructure. Having roads is an absolutely amazing thing. There is a tendency to under-invest in the health of the poorest and as you said it does not pay off immediately; the child to death rate is rarely brought up during a political conversation and so the SDGs are a tool to remind people how important it is that all these children are surviving, all of these children are growing up in a healthy way. India is making progress in both health and infrastructure.

Q But it has been a hard bargain to drive even in India, to get the government to agree to spend more on health. You have been waging that battle for a while...

Right. I would say the best progress has been on taking more risk and making sure that the quality of the system, the number of kids who get vaccines gets improved. I agree there is a limit on how far it can go. India is a lively democracy; people will debate that thing (spends on health), but compared to other countries, the investment level probably does need to be more of a priority.

Q Have you looked at the health insurance scheme (Ayushman Bharat) that Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi has announced? How could that impact India’s health goals?

We are working with Niti Aayog...we spoke about how other countries have brought in insurance, how they use private sector capacity to help in the health sector. There is some good long-term planning and over time this goal of having insurance more broadly is important. However, the affordability challenge means that the health sector will have to get more resources for you to get up to any substantial coverage level.

Q We have a Right to Education Act that is now a decade old. So while we may have addressed the enrolment challenge quite effectively, the quality of education continues to be a cause for concern. What is the way forward when you look at India?

There are exemplars. Look at the way a country like Vietnam, which is substantially poorer than India, trains their teachers. It insists that the teachers be good at their job, and has lots of ways of measuring that and providing feedback. It is now at a level of education that is competitive with the richer countries and so it is quite an outlier. India has done well on access, but when it comes to the amount of learning—which is a recent thing to measure, not just the attendance but the learning—India has a lot of room for improvement. In fact given how much the Indian economy has grown, it has fallen behind on the quality of its learning outcomes.

Q Is this going to be a space that you would want to focus more on? Will education be a focus area for the foundation in India?

Our biggest spending on education by far is in our own country, the US. Globally we have health and agriculture; in the US we have education. We are starting to take some of the lessons and are willing to share with governments that are interested. We are working with the Central Square Foundation in India; we will be a partner, helping share best practices for the Indian states that want to (partner with us).

It is always a risk that countries are turning inward and certainly there are political leaders now who are more nationalistic than thinking about all of humanity.

Q On agriculture, the challenge in India today is that at one level you have record production, but farm income has declined over the last few years. How do you ensure that this promise that the government has made about doubling farm income becomes a reality?

A big reason why the Asian exemplars, and China is by far the biggest, are able to drive up economic growth is that they are able to make farm efficiency productivity for labour much higher. That freed up labour went into other activities. In their (China’s) case, they have the right policies to be competitive in global manufacturing, they have the logistics, infrastructure, labour and land laws that resulted in that (manufacturing) becoming the primary source of increased employment.

Q Labour is one of the challenges that you speak of in the report where significant progress has been made especially on poverty alleviation. But now you believe it is going to be a challenge because it collides with the demographic reality. What is the way forward?

Reducing extreme poverty is an ambitious goal, and it has gone down a lot. China was the biggest contributor, India was the second biggest contributor. There are some clear policies (enabling this reduction): Getting kids in school, understanding malnutrition, for which India has a whole mission organised... on which they are a lot smarter about how they can get those levels down.

So Asia as a whole with few exceptions, like Yemen or Afghanistan, is on a track to take extreme poverty down to low levels. China wants to go all the way to zero, and it has an impressive programme to do that. The place that is a concern is Africa. The population growth in Africa is high; there are only a billion people there today but, by the end of the century, that will be up to 4 billion. Most of the population growth on the entire planet is in the continent that is by far the poorest. So it is going to be a challenge to keep making progress on extreme poverty unless we take lessons from India and China and apply those in Africa, particularly in larger countries in Africa.

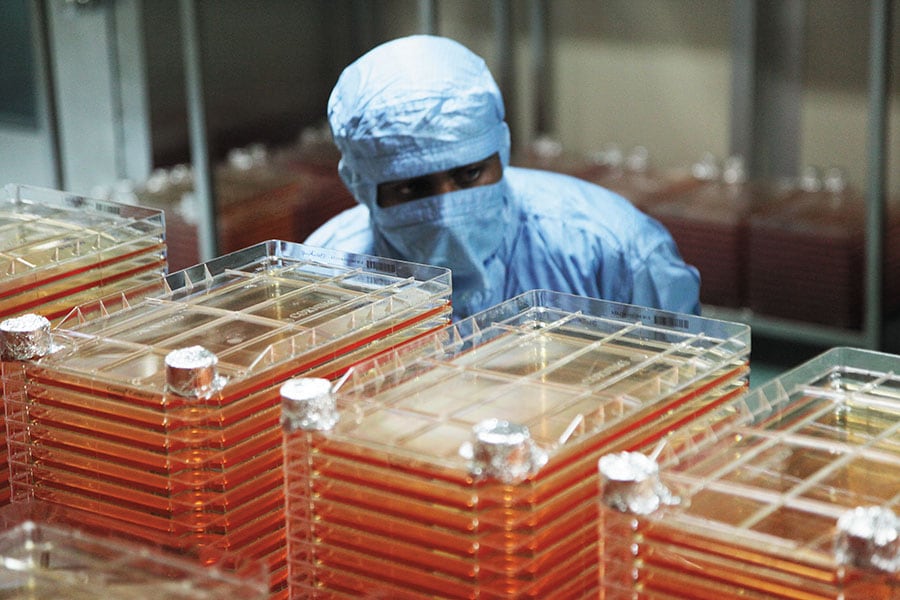

By keeping the quality of its drug regulation high, India has been able to make significant progress in the health sector. It has adopted the rotavirus vaccine while the pneumococcus vaccine is starting to be rolled out; Image: Pallava Bagla / Corbis via Getty Images

By keeping the quality of its drug regulation high, India has been able to make significant progress in the health sector. It has adopted the rotavirus vaccine while the pneumococcus vaccine is starting to be rolled out; Image: Pallava Bagla / Corbis via Getty ImagesQ Last year you were candid that perhaps we would miss some of the SD targets. Do you feel a little more confident about meeting them today?

We are making good progress on the health goals; there’s the kind of upstream innovation where we need new tools like an HIV vaccine, a TB vaccine, seeds that can deal with drought because of climate change. The innovation piece has moved faster than I would have expected. The global priority of helping everyone, including the poorest, is always a little bit crowded out by near-term challenges. Whether it is Brexit or the US trade policies, political commitment is not guaranteed and it is possible that the issue of helping Africa or the poorest will get lost in all the other noise.

I haven’t seen him for a number of months. He has got a new secretary of state with whom I talked about Africa and about how we work with the US government.

Q What was the response?

The budget levels have been maintained and so have the US role in HIV reduction, malaria attack… there is a lot that the US has prioritised and continues to fund at various generous levels. Over half the money that goes to Africa to help solve those problems comes out of the US. Will all these trade issues overwhelm that, how does that affect some of these fragile economies? There is always plenty to be worried about; which of these policy choices would avoid creating damage to those most in need... we see that as a key role that we play.

Q About $15.5 billion over the last ten years has been spent by the foundation on the vaccine programme. What role do you see specifically for India from this perspective because it is a generic hub?

India—by keeping the quality of its drug regulation high—has been able to serve its own needs with low-cost vaccines. We provided hundreds of millions of dollars to these organisations to help them build factories, create new products, make sure that they are taking a high-volume, low-price approach. It is fantastic that India adopted the rotavirus vaccine; it has been over 20 years until a new adoption has happened—the pneumococcus vaccine is starting to be rolled out.

Q What about sanitation, which is PM Modi’s pet project? You have worked with the government on many levels on this front. What gives you the confidence that we will be able to achieve the targets that have been set?

We are partnering with Indian companies to say how can you either process waste or eventually have a toilet that doesn’t create that waste. Most governments don’t talk about sanitation and so it is a hidden problem. It takes political leadership because you have to have capital investment, you have to say dumping sewage into the rivers is no longer going to be allowed. We have a number of projects that are going on with new processing techniques, bringing the cost of that processing down. We had our toilet fair in India where we showed some of those new innovations. The toilet fair will later this year be done in China because there are manufacturers there that are going to be making some of those pieces. So India and China are big partners.