Healthy in the wrong way: When food marketers don't listen

The meaning of "healthy" is constantly evolving, and food marketers are not always meeting consumers' expectations

Cereal packaging also makes numerous health claims despite the product having a mediocre nutritional quality.

Image: Shutterstock

Cereal packaging also makes numerous health claims despite the product having a mediocre nutritional quality.

Image: Shutterstock

It is almost impossible to buy food these days that does not purport to be healthy in one way or another. Everyone wants to make healthier eating choices, and food companies often try to present food as healthier than it really is, as I have outlined in previous Knowledge articles based on my research.

However, there is no agreement among experts, and certainly not consumers, about what “healthy” even means. For example, Kellogg’s sued the UK government over new regulations limiting the in-store promotion of foods that are high in fat, salt and sugar. The company argued that the formula used to measure nutritional value did not consider the nutritional elements added when its breakfast cereals are consumed with milk. It lost.

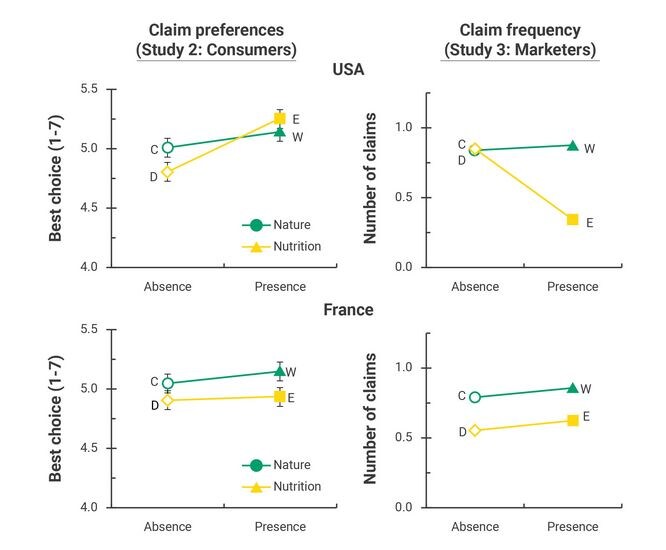

As the number of products that claim to be healthy increases, so does consumer distrust that they really are. A recent European study found that only 43 percent of consumers think that food products are generally healthy, and just 46 percent trust food producers. The growing disagreement over what it means for food to be healthy suggests that marketers’ claims do not match consumers’ expectations.

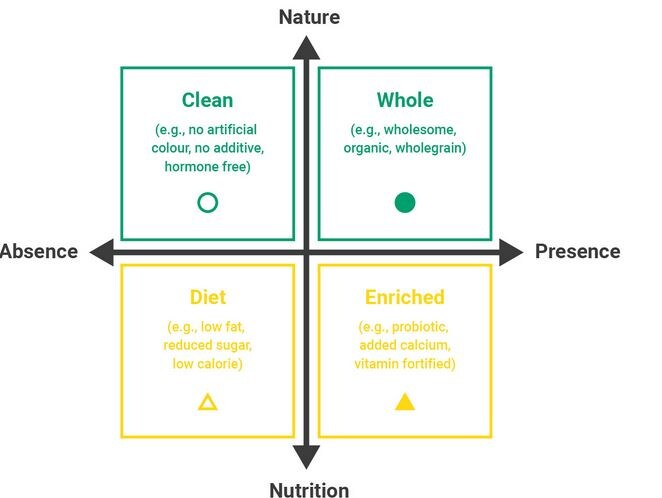

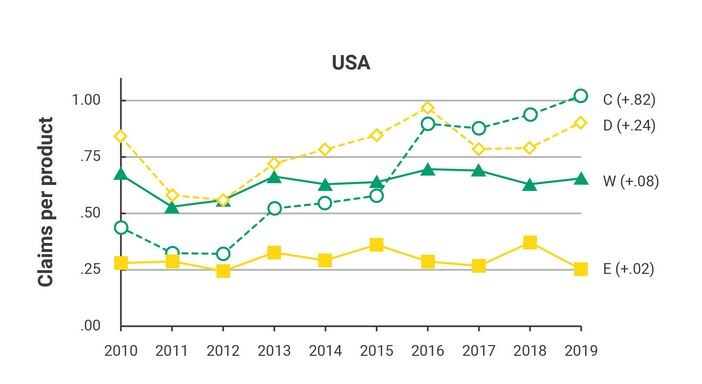

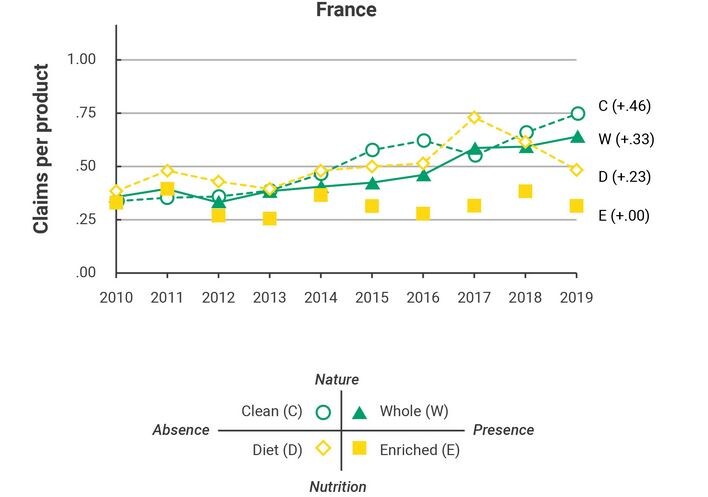

In order to investigate this further, Romain Cadario and I examined the ways food companies have labelled food products as healthy over the past decade and contrasted this behaviour with the preferences and associations of consumers.

Our research, published in the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, focuses on breakfast cereals in France and the United States. We chose this product category as it is popular and dominated by the same companies in both countries. Cereal packaging also makes numerous health claims despite the product having a mediocre nutritional quality.

[This article is republished courtesy of INSEAD Knowledge, the portal to the latest business insights and views of The Business School of the World. Copyright INSEAD 2024]