- Home

- Lists

- India Rich List 2020

- India's Richest: Meet the ice cream billionaire

India's Richest: Meet the ice cream billionaire

From a small ice candy factory, RG Chandramogan has steered Hatsun Agro Products to becoming the biggest private sector dairy company in the country. And, at 71, he is set to expand the business further

Manu Balachandran is a writer for Forbes India, based in Bengaluru. At Forbes India, Manu writes on automobiles, aviation, pharmaceuticals, banking, infrastructure, economy and long profiles among many others. He also moderates many of Forbes India's CEO and CXO events and hosts Capital Ideas, a podcast on the most riveting success stories from the business world. He has previously worked with Quartz, The Economic Times and Business Standard in Mumbai and New Delhi. Manu has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University and a degree in economics from the Loyola College. When not chasing stories, he is most likely obsessing over Formula 1 (Read: Lewis Hamilton), historical events and people, or planning long weekend drives from Bengaluru

G Chandramogan loves numbers. In fact, back in school, mathematics was among his favourite subjects.

“Everybody around me knows that I am good with numbers,” says the chairman and managing director of Chennai-based Hatsun Agro Products, India’s largest private sector dairy company. “All my life I have been fascinated by numbers. There was a time when I used to remember phone numbers before mobile phones came by.”

Related stories

His close aides reckon the 71-year-old is a prodigy, almost like a human computer when it comes to calculations, down to the last decimal. “Many of us need calculators to do maths,” says H Ramachandran, the chief financial officer of Hatsun Agro Products. “With him, however, all that calculation is in his head.”

Perhaps it’s ironic then that it was failing at mathematics that helped him make a tryst with destiny many years ago. Five decades ago, Chandramogan failed his mathematics exam while appearing for his pre-university course (PUC), a precursor to college education. He attempted it once again a year later, but walked out of the hall a few minutes into the examination.

“My mind was in turmoil while appearing for those papers,” Chandramogan says. Much of the distress was due to his family’s dwindling fortunes, after his father’s small-time provision store closed. “That’s when I knew I had to chart my path,” he says.

A year or so later, with seed money of Rs 13,000 from his father, he set up a factory to make ice cream candies. Today, Chandramogan is worth $1.3 billion, making him India’s 100th richest person, and earning him a place on the Forbes India Rich List. His company Hatsun Agro Products has made giant strides in the dairy industry, and is today the country’s largest private dairy company by sales. Hatsun procures close to 33 lakh litres of milk everyday from over 4 lakh farmers and sells milk, curd, ice creams and ghee through its brands Arun Ice Creams, Arokya Milk, Hatsun Curd, Hatsun Paneer and Ibaco.

Hatsun, a play on ‘Hot Sun’, exports its products to over 38 countries around the world, particularly the US, the Middle East and South Asian markets. Within India, much of the company’s focus remains on the South Indian market, where it controls nearly 17 percent of all the milk sold, according to Chandramogan, and over 40 percent of the ice cream market.

“We are dominant in southern India,” Chandramogan says. “Today, the turnover we make in 30 minutes is equal to what we used to make in the first 10 years of our business.” Hatsun Agro Products was set up in 1970 with four employees in a rented facility in Chennai, with capital raised from selling the family’s ancestral property. Today, the company has a market capitalisation in excess of Rs 13,000 crore, with revenues clocking over Rs 5,300 crore.

“We went from being a small company to a medium one and then to a big one,” Chandramogan says. “Now we are in the middle of a transition into a large company.”

Push-carting to billions

Chandramogan’s entry into the Rich List hasn’t been an easy one.

Born in a poor family in the nondescript village of Thiruthangal in southern Tamil Nadu, Chandramogan says he always knew that he wanted to be an entrepreneur. “In my village, most of the successful people were businessmen,” he says. “We were not exposed to successful people with a career in the corporate world in those days.”

While the family owned a few ancestral properties in the rain-deficit village, there wasn’t much income to sustain the household. So Chandramogan’s father moved to Madras, now Chennai, and set up a provision store in 1956 near the Chennai Central Station. “But he was of a philanthropic mindset and his interest was in social work,” Chandramogan says. “By 1968, we had to wind up the business and he went back to my hometown.”

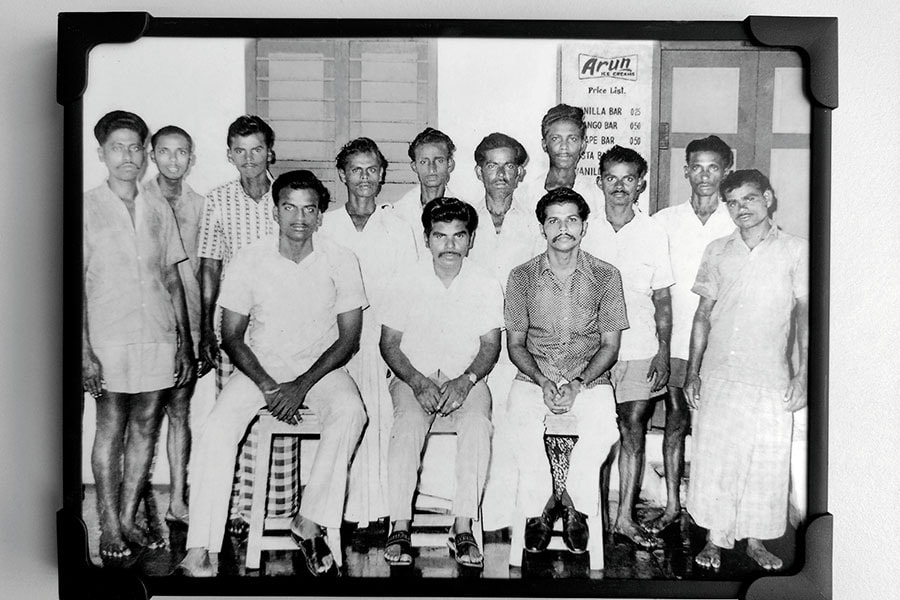

RC Chandramogan (seated, first from left) at the first factory of Arun Ice Creams, with pushcart vendors standing behind

RC Chandramogan (seated, first from left) at the first factory of Arun Ice Creams, with pushcart vendors standing behind

Courtesy: Hatsun

But Chandramogan’s father had ambitious plans for his son—he wanted him to study and move to the US. “I argued with him, that I would join his business, which was closing, and work out a way,” Chandramogan says. “He was staunchly against it and probably didn’t trust me. One thing I was sure of was that he wouldn’t be able to sponsor my ticket to the US. So there was no point in pursuing that dream. Every father has an ambition for his child, and mine did too, without the resources.”

Soon, he enrolled at St Xavier’s College in Palayamkottai for his PUC, where he failed in mathematics. “I was an outstanding student, but this particular turmoil hadn’t helped,” Chandramogan says about his father’s business collapsing. “In my village, not many people go for college education, and it was more common for people to start a business.”

His father then found him a job at a timber depot as an apprentice in Viluppuram, about 160 km from Chennai, on a salary of Rs 65. “I worked there for a year, and then came back to Chennai,” Chandramogan says. That’s also when he decided he would focus on becoming an entrepreneur. “To accommodate the son, who wasn’t up to his expectations, my father sold our ancestral land for Rs 13,000,” Chandramogan says. That became his seed capital, though his father believed the money was “marooned”.

Chandramogan shortlisted about seven prospective businesses, including setting up a movie theatre and exporting dehydrated onions. “But there were budget constraints,” he explains. “One has to look for a business that suits the capital. Beggars cannot be choosers.” So he decided to set up a small ice candy factory in a rented 250-sq ft space in Royapuram with four employees in 1970. By then, Chandramogan was 21.

The factory could churn out 10,000 ice candies per day and he sold them under the ‘Arun’ brand in Chennai. Arun, Chandramogan says, was a shortened form of Arunodayam, which in Tamil means ‘sun rays’. By night, the factory would also turn into his bedroom.

A Hatsun ice cream outlet in Kerala. The company is a dominant player in South India

A Hatsun ice cream outlet in Kerala. The company is a dominant player in South India

Courtesy: Hatsun

Back then, Chandramogan reckons there were some 40,000 companies selling ice candies across India. The candies were sold on pushcarts by vendors, and there were some 3,000 such factories in Tamil Nadu alone. “I wanted to prosper. I found there was no way I was going to [always] sell ice candy to vendors,” he says. “I decided to move into the league of the biggies.”

Back then, the ice cream industry in Tamil Nadu was dominated by Dasaprakash Ice Cream, followed by Mumbai-based Joy Ice Cream and Kwality Ice Cream, owned by Hindustan Unilever. To beat them, Chandramogan knew he needed enormous financial clout.

“We were the wrong people at the wrong time in the wrong market,” he says. “But having come into it, we started adapting and made a lot of sacrifices, to become the largest dairy company.”

With limited capital, the 21-year-old laid out elaborate plans. The ice cream market in Tamil Nadu comprised five major categories, he says. These included shops and supermarkets, hotels, wedding parties, colleges and ships that would come into Chennai. Of this, the shops, hotels, and wedding industries were largely dominated by the big players. “The first three businesses were capital-intensive,” Chandramogan says. “We needed deep freezers, supply credit and customers also looked for a brand. We didn’t have the muscle power or money. Even if we put in freezers, no customer was willing to buy my brand.”

Together, these businesses accounted for almost 90 percent of the ice cream industry in Chennai. The remaining 10 percent were the colleges and ships. “The college messes were run by secretaries, who were 18 to 20-year-olds. I was around that age,” Chandramogan says. It also helped that they were looking for reliable partners, with dependable supplies and good quality.

That opened up a huge market, and Arun began ploughing back the money into ramping up technology and machinery. “The investment was huge and we got a technocrat to manage the factory,” says Chandramogan. “Then we began to penetrate the college market. The big companies were looking at these colleges as small customers.”

The same was true for the ships that docked at Chennai.“As far as they were concerned, if the taste was acceptable, and the delivery was prompt, they were willing to buy,” he says. “Suddenly, of the 10 percent market, we started holding a 90 percent share.”

The big break

Over the next few years, the company largely remained stagnant, until they set up an ice cream parlour in Chennai in 1978, and then decided to venture into small towns and rural markets. “The ice cream market was confined to big cities because ice cream was still consumed [mainly] by the urban population. We thought, why not try the outstation market.”

Over the next few years, the company ventured into towns such as Erode, Tuticorin, Tirunelveli, Salem and Kumbakonam. The company also developed a franchise model, with owners being asked to invest in the machinery, including deep freezers to store the ice creams that would be brought from Chennai. The franchisees were also given an exclusive territory. “All this while the three big players didn’t know the rural market,” Chandramogan says. “They dominated Chennai with their brands, we went to this market, and it started growing.”

By 1984, he says, Arun Ice Creams was the largest manufacturer of ice cream in Tamil Nadu, and began to invest heavily in developing its Chennai market. “We became number one in Chennai in 1987,” Chandramogan says. Soon, it also expanded to Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, making it one of the largest in the South Indian market.

This also meant investing heavily in technology. “We never shied away from investing in technology,” Chandramogan says. “We were highly leveraged then, and I used to joke that I was only a glorified employee of the banks because our debt-equity was around 1:5. But we kept using the money to invest in state-of-the-art technologies. While we borrowed from banks, we were never to borrow from suppliers.”

In 1995 the company decided to foray into the dairy business by launching the ‘Arokya’ brand of milk in Salem, Tamil Nadu. The company already had a manufacturing facility in Salem and was procuring milk for ice cream for it. But the dairy business was dominated by cooperatives backed by the state government.

Dairy farmers line up at a Hatsun milk procurement centre in Dharmapuri, Tamil Nadu. The fresh milk is tested for quality and is weighed. A digital board (on the left) displays various parameters and procurement rates. An SMS is sent to the farmer’s mobile phone with the details

Dairy farmers line up at a Hatsun milk procurement centre in Dharmapuri, Tamil Nadu. The fresh milk is tested for quality and is weighed. A digital board (on the left) displays various parameters and procurement rates. An SMS is sent to the farmer’s mobile phone with the details

Courtesy: Hatsun

“It was considered a service industry to people,” Chandramogan says. “The cooperatives were able to have a much lower price compared to private companies. They were running a non-profitable business.”

It also meant that companies foraying into the market had to match pricing, leading to serious losses. “Over time, people were shutting down [their business]. They either had to reduce the quality or price,” Chandramogan says. “All our people too said we should price our product lower than the cooperatives. But I said then we don’t stand a chance of running for long. So we will go for product differentiation.”

While most of the rivals were trying to sell a variant of toned milk with 3 percent fat, Chandramogan decided to sell milk with 4.5 percent fat. “If we went in without a product differentiator, we would have collapsed. Because the costs weren’t going to match. I was not going to compromise on the quality and reduce the price.” The company launched its milk at the existing rate of `7.50 and, over time, raised it to match the real cost. The idea behind selling milk with 4.5 percent fat was also because Chandramogan felt it was better for children’s growth.

Today, a bulk of the company’s sales comes from milk with 4.5 percent and 6 percent fat, while the 3 percent category remains minuscule.

Besides, Hatsun began to procure milk directly from farmers. “Again there was opposition, saying it’s an expensive route,” Chandramogan says. “Milk is a perishable commodity. Once you collect, the variable cost will go out of control. Our people said it is foolish. But I insisted on this model. It took some time, but we established our credentials.” It also helped that Arun Ice Creams was a market leader, which meant farmers came on board more easily.

Over the next 10 years, Hatsun focussed on its dairy business, although it came at the cost of its ice cream business.

Today, it procures milk through its network of around 10,000 Hatsun Milk Banks. Every farmer has a unique producer code linked to their bank account and is paid once in 10 days. The company also claims to be the world’s first dairy company to develop and use thermal battery-based technology in its Bulk Milk Coolers for chilling milk immediately after procurement.

“We don’t invest in unwanted property, unwanted share investments etc. All our investment is only into this business. We don’t live a very extravagant life.” It also helped that the company enforced financial discipline, ensuring that all delivery was made against payments. “So, financially we were able to rotate the working capital much better,” Chandramogan says.

The ice cream business contributes about 11 percent of overall revenue. “The consumer base is bigger in ice creams, but the frequency varies,” Chandramogan says. “In the dairy business, it is a 365-day affair.”

The way ahead

Now, with much of the South Indian market under its control, Hatsun is gearing up to boost its play in the rest of the country.

It has set up two manufacturing plants in Maharashtra and has forayed into Odisha. “We are focusing on expanding in one state at a time,” Chandramogan says. In all, the company operates 20 plants across the country. These include nine milk processing and packaging units, two milk product manufacturing units, and two ice cream manufacturing units, among others.

India is the world’s largest producer of milk and its dairy industry is worth around `6 lakh crore, according to an Edelweiss report. Only about 20 percent of the market is organised, with milk cooperatives, including Amul, Nandini and Mother Dairy, dominating the industry.

“There is tremendous opportunity in the dairy sector for Hatsun to grow,” says Nitin Puri, senior president and global head for food and agriculture research at Yes Bank. “Almost two-thirds of the industry is in the unorganised category. With the Covid-19 crisis, there is a massive disruption, particularly in customer preferences for buying milk. Hatsun has managed to crack the sector well, and has managed to build a scalable business.”

A bulk of that, Puri reckons, is also due to Hatsun’s early foray into direct procurement from farmers. “Much before many others forayed into direct procurement, Hatsun engaged with farmers directly. That helped them secure their back-end, and they also kept innovating, such as with the thermal battery-based milk coolers for areas with poor electricity.”

All of which means Chandramogan isn’t ready to hang up his boots anytime soon. “Since 2015, we began to focus on ice creams again,” the billionaire says. “We are now seeing faster growth in the business and we want to grow it further. Among the 40,000 similar ice candy manufacturers who ran a cottage industry in 1970 like us, we are the only ones who made it to the big league in the entire country.”

Has becoming a billionaire changed anything? “All this is notional wealth,” Chandramogan says. “I don’t consider myself to be a billionaire. In fact, the only asset I have is a house.”