India's Richest 2019: Haldiram's incredible success story

How a simple snack took a Bikaner family from a small chawl to the list of billionaires

Delhi-based Haldiram Snacks has grown to be the largest in the Haldiram family

Delhi-based Haldiram Snacks has grown to be the largest in the Haldiram familyImage: Madhu Kapparath

The heights by great men, reached and kept,

Were not attained by sudden flight.

But they, while their companions slept,

Were toiling upwards in the night.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

The story of Haldiram’s success is of ordinary men achieving extraordinary feats. What began in 1918 as a part-time hobby for extra income has today become a behemoth enterprise in the food industry in India generating close to ₹5,000 crore in annual revenues. The business that began in a small shop now spans not only all regions of the country, but also has a tremendous following globally.

How did they achieve such a feat? How did they go from a small chawl in Bikaner, where at one point 13 people slept, to debuting on the 2019 Forbes India Rich List?

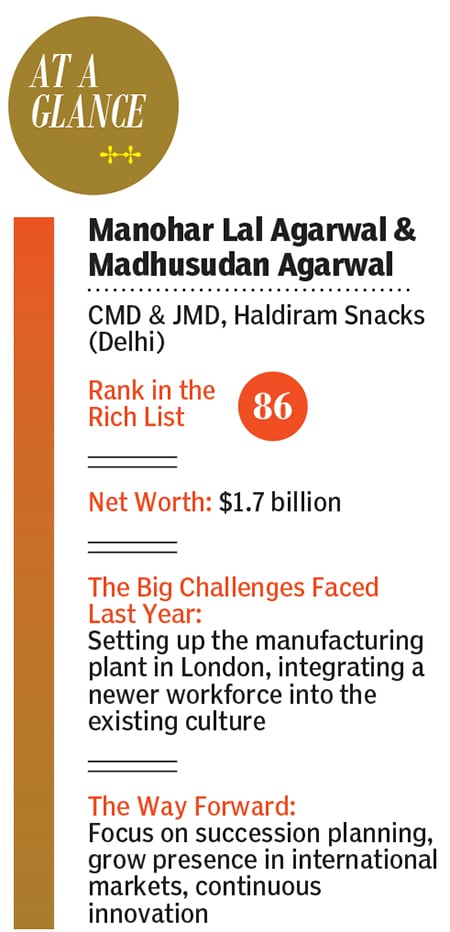

Many businesses survive because of an uncanny sense of how to run operations, an understanding of customers and differentiation in products. In addition to these, the one thing that sets Haldiram’s apart is their indefatigable grit and ability to persist regardless of the obstacles. This is especially true for the Delhi owners, Manohar Lal and Madhusudan, who have been ranked 86th on the list with an estimated net worth of $1.7 billion.

The dawn of the brand

At the age of 12, when most children went to school and were busy copying notes off a dusty blackboard, Ganga Bhishen Agarwal spent his days in Bikaner inventing the ubiquitous snack we today know as Haldiram’s bhujia and reiterating the product to make it more irresistible to customers. The most important changes he made to the bhujia was making it out of moth ki dal rather than besan, which made it a delicacy overnight as moth is very popular and easily available in Rajasthan. He also focussed on making it the fine crispy bhujia we know today transforming it from the fat, slightly bland version from before his time. The boy in his early days in business also demonstrated a knack for marketing by setting the price point such that the product was more exclusive and not just considered a commodity, selling for 5 paise a kilo as opposed to the earlier 2 paise under his grandfather Bhikharam. He went further by naming it ‘Dungar Sev’, after the then Maharaja Dungar Singh, adding aspirational appeal to the brand.

By the early 1930s, the price of bhujia went up from 2 paise a kilo to 25 paise, making it a successful business venture for the whole family to live off. Merchants on their way to Kolkata stopped by to purchase this bhujia for friends and family back home and the seeds of a global empire began to be sowed.

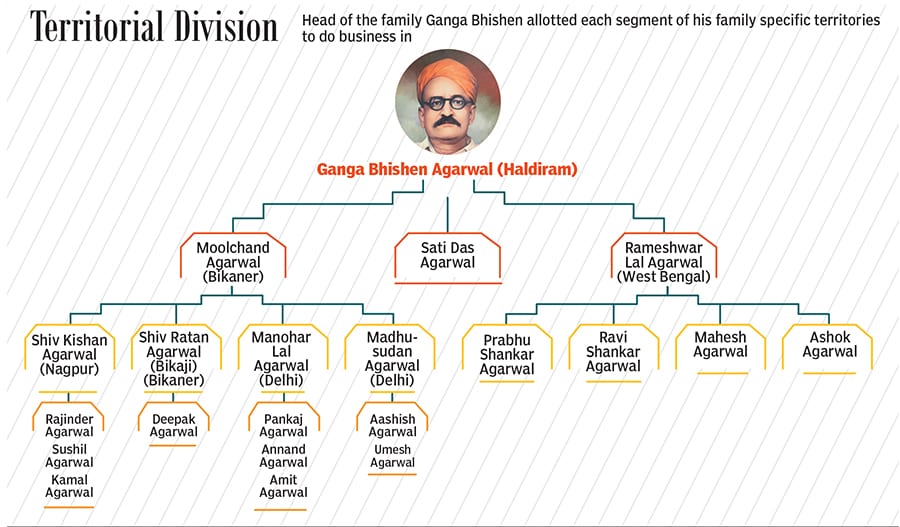

In the early 1950s, Ganga Bhishen, along with his sons (Moolchand and Rameshwar Lal), took a leap of faith with the help of well-wishers and opened a business in Kolkata (Haldiram Bhujiawala which later split into Haldiram’s Prabhuji and Haldiram) that became a huge success within a few years. There was no looking back after that. In the next three decades, the business migrated to Nagpur (Shiv Kishen Agarwal) and then the capital (Manohar Lal Agarwal and Madhusudan Agarwal).

The Delhi branch

Manohar Lal and Madhusudan, the youngest sons of Moolchand, fought the quintessential battle with their father to strike out independently. The Agarwal family was vehemently opposed to the idea of debt or taking loans. Organic growth was their mantra. When the time came to invest in Delhi, Manohar Lal and his older brother Shiv Kishan were forced to withdraw all their hard-earned savings and put their shirts on the line. Business began in 1983 in Chandni Chowk but, unlike the other cities they had ventured into, bhujia was not a unique product in Delhi. The brothers faced immense competition from established players such as Ghantewala and Bikanerwala. Strategically, they differentiated themselves by focusing on adjusting flavours and innovating to meet the needs of the market and soon began to break even.

However, just when the family business was finding its feet, in a tragic turn of events, their shop and apartment were burnt down in a fire during the 1984 Sikh riots. Manohar Lal, though, remained steadfast, and after sending his family back to Bikaner, toiled along with Madhusudan to build the business back up, brick by brick. Delhi was not going to kick him out.

Unlike his predecessors, Manohar Lal had gone to college and had a keen eye for processes. This was the opportunity to start afresh and set up a business that would be the foundation for the empire today. Innovation and automation were the pillars for the young owners who dreamt of building a business whose products would reach people in the farthest corners of the country. They started with rebuilding their shop. Once business picked up, they turned their apartment into a factory overnight, where the entire family pulled long sleepless nights, trying to keep up with demand. Soon, the Chandni Chowk location was not enough and Manohar Lal began looking for factory space to begin large-scale production. The first factory was set up in the late ’80s. After that, distribution became one of their greatest strengths, one of the secrets to their success in the capital. A testament of their success is that today at railway stations and stalls around the country, the ₹5 Haldiram’s bhujia packet is used as currency, as a substitute for loose change.

Internal Politics

Like most family businesses, the Haldiram family was not immune to disputes of inheritance. Early on in the family’s journey, Ganga Bhishan put a rest to the family feud through a unique system of territorial division wherein each segment of the family would only be able to do business in the territories assigned to them. With this agreement, Rameshwar Lal and his sons were only allowed to do business in West Bengal. While initially, when sales were great, this agreement worked out, over the years, as other family branches began to grow the business in the capital and across the country, the arrangement began to feel like sour grapes.

In 1991, the Kolkata family made inroads into Delhi, refusing to alter their brand name to distinguish themselves from the Delhi brand, thereby incurring a court case. The case went on for almost 15 years, eating into not just the family’s resources but also affecting emotional ties. Finally, in 2013, Delhi’s Haldiram’s became the sole owner of the trademark 'Haldiram Bhujiawala'. While the Kolkata family might still have a couple of shops in Delhi, with the strength of the Delhi empire and their loyal customer following, Haldiram’s Delhi finally has the might to ignore these tiny intrusions.

(From left) Moolchand Agarwal’s sons Madhusudhan Agarwal, Shiv Kishan Agarwal (sitting), Shiv Ratan Agarwal and Manohar Lal Agarwal

(From left) Moolchand Agarwal’s sons Madhusudhan Agarwal, Shiv Kishan Agarwal (sitting), Shiv Ratan Agarwal and Manohar Lal AgarwalWhat lies ahead?

While largely remaining closely guarded from the prying eyes of the public, Manohar Lal and his brother have been pushing boundaries in business. The recent venture with the second largest bakery chain in the world, Brioche Dorée, is proof that Haldiram’s is set on broadening their reach. For the first time, the bakeries will only be serving vegetarian food tailored to the Indian market.

Similar to PepsiCo in the past, breakfast products giant Kellogg’s has also recently shown interest in partnering with or buying a stake in Haldiram’s (Nagpur and Delhi enterprises), valuing them at $3 billion. Talks are on and it is yet to be seen whether this will turn into a partnership or a merger given Haldiram’s propensity to hold the reins of the family business close.

While the brand is thrilled that Manohar Lal and Madhusudan have debuted on the 2019 Forbes India Rich List, the attitude is still grounded. “We are thankful to our customers for our growth. We have only reached this position by the grace of God and also because of our customer’s faith and trust in us. We will continue to endeavour to delight our customers in the future. This is also the result of the dedication, loyalty and hard work of our employees,” says Manohar Lal.

While innovating on product is at the forefront for the company, ambitions for international expansion have driven them to set up a state-of-the-art factory in London to serve the demand for Indian sweets in Europe. They hope to take this forward to other shores once the success of this model has been proven.

Though growth has been tremendous, they also face several challenges. The family business is now slowly opening its doors and roping in professionals. While this will improve processes and help Haldiram’s become a world-class organisation, they have to manage the balance between new professionals and traditional employees who believe in immediate access to the family.

The family also needs to have an eye on succession planning. The difference between some of the giants in family businesses such as Johnson & Johnson and those that die out is a system that works and allows the organisation to evolve and grow with each generation. Haldiram’s is focussed on developing their credo and process in an endeavour to support future growth.

● (Pavitra Kumar is the author of Bhujia Barons published by Penguin Random House India)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)