Samina Vaziralli: The patient healer

Preparing Cipla to compete in a complex world while preserving the pharma company's ethos is the challenge that YK Hamied's niece has happily accepted

Image: Vikas Khot

Image: Vikas Khot

Nestled a few metres away from a bustling thoroughfare in central Mumbai is the office where it all began for Cipla, one of India’s oldest pharmaceutical companies. Founded by scientist Khwaja Abdul (KA) Hamied in 1935, the pharma major is an extension of his nationalistic spirit through which he wanted to serve people by making affordable medicines for the masses.

On a sultry October afternoon, standing in front of the imposing building in central Mumbai, Yusuf Khwaja (YK) Hamied—the company’s non-executive chairman who, at 81, is just a year younger than Cipla—points to the ground where he’s standing and proudly asserts that Mahatma Gandhi once stood there.

YK Hamied (ranked 60 on the 2017 Forbes India Rich List with a net worth of $2.62 billion) is as illustrious as his father, who was not only a disciple of Gandhi but also well-known to the man who led India’s freedom struggle. The son took on the might of leading pharma firms in the quest to sell affordable life-saving drugs for those suffering from AIDS in the developing world at a minimal cost of $1 per day. Other manufacturers sold the same drugs at around $12,000 per patient per year.

It is this enduring legacy spanning eight decades that YK Hamied’s niece Samina Vaziralli, 41, has inherited. But with the weight of a rich history comes the burden of challenges too. Since being appointed executive vice-chairman in 2016, she has been charting Cipla’s future course while ensuring that the company’s reputation only grows stronger. Vaziralli, the daughter of YK Hamied’s brother, Mustafa Khwaja (MK) Hamied (77), had no prior experience in pharma before joining Cipla in 2011. However, the postgraduate in international finance from the London School of Economics and Political Science believes her fresh and pragmatic approach along with an empowered senior management will aid her gumption to take bold bets and rejuvenate the pharma giant.

Cipla’s primary aim when it started operations was to cater to Indians. It has lived up to that promise and has one of the largest field forces (of around 10,000 medical representatives) and marketing setups in the country. Also, unlike peers such as Sun Pharma and Lupin that earn a big portion of their revenues from the US and other global markets, Cipla still garners a majority of its topline from India (around 40 percent compared with, say, Lupin’s 22 percent).

The pharma major spent a significant amount of resources for its global crusade against AIDS and making affordable medicines for other life-threatening diseases. In the process, the $2.2 billion (by revenues)company had to forego other avenues of growth. Most notably, the lack of a front-end marketing setup in the US—the largest and most lucrative market for generic drugs in the world. Cipla has a presence across key therapeutic areas, including respiratory, oncology, cardiovascular, diabetes, hepatitis and infectious diseases. And while it had a presence in over 120 countries, its existence in major markets was mostly through partnering other pharma companies. The partners would market end-products based on the intellectual property that Cipla developed and passed on to them. The upside to such a model was limited as pharma companies that market drugs themselves are the ones that realise the maximum value from the business.

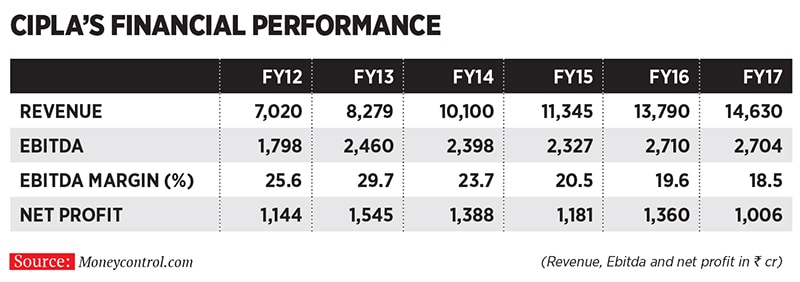

These factors, compounded by the challenges in the pharmaceuticals space, including pricing pressure and intense competition in the US and India, have led to modest growth in Cipla’s earnings (See box Financial Performance) compared to its peers. It is a reality that Vaziralli is aware of.

The biggest challenge before Cipla today is to catch up. “We were an India-focussed company with a front-end setup only in the country and growing organically,” says Vaziralli. “We were a great partner of choice, but we remained in the back end, using our R&D and manufacturing capabilities to unlock commercial value for others. Today Cipla has built front-ends in the US, South Africa and several emerging markets where we have a leadership position.”

Samina Vaziralli is the bridge between Cipla’s professional management and the board, whose members include her uncle YK Hamied (extreme left) and father MK Hamied (extreme right)

Image: Vikas Khot

Cipla is now narrowing the canvas in which it operates by exiting some countries and focusing on select business areas and geographies. The front-end in the US was established in January 2015 and bolstered with the acquisition of two US-based companies, InvaGen Pharmaceuticals and Exelan Pharmaceuticals. The acquisitions were announced in September 2015 and completed in February 2016.

As part of its growth strategy, Cipla also wants to move up the value chain and make complex generics and specialty drugs. It plans to file for 25 ANDAs (abbreviated new drug applications) with the US regulator in FY18 and launch as many as 10 products in the remaining months of this fiscal. The company already has 238 ANDAs in the US, including those that are approved and those awaiting regulatory nod. Cipla also wants to focus on its existing business in South Africa and emerging markets such as Brazil and China, Vaziralli tells Forbes India.

India, too, is an integral part of its scheme. In India, the focus is on getting into in-licensing partnerships with global innovators like Novartis and Janssen and selling their drugs in the country. This strategy is also a hedge against the price control on vanilla generic drugs exercised by local regulators. Being innovator drugs, they are outside the purview of price control.

Its past challenges notwithstanding, analysts appear enthusiastic about Cipla’s prospects. “We expect earnings to improve, given that it [Cipla] is scaling up in the US business, trimming costs and rationalising business,” says Param Desai, an analyst with Elara Capital, in a research report dated August 11.

The management churn that Cipla witnessed in the past was also a challenge for the company. Since 2013, Cipla has had two CEOs and four chief financial officers (CFO). Some other key members of the erstwhile management also quit in this period.

“We hired people at a time when we were just embarking on this journey of transformation and the journey gathered pace quicker than we could imagine,” says Vaziralli. “Some of the talent wasn’t ready for that second turn of transformation.”

However, the current senior leadership (apart from Vaziralli) helmed by MD & Global CEO Umang Vohra and Global CFO Kedar Upadhye are holding fort and have the freedom to run the company in the manner they deem fit. Cipla is the only large family-owned pharmaceutical company in India that has a non-promoter CEO. Vohra, 46, was heading Dr Reddy’s Laboratories’ generics business in North America before joining Cipla as chief operating officer in 2015.

After taking over as CEO, says Vohra, Vaziralli and he sat down to chalk out the remit of their respective roles. The day-to-day operations, including the acquisition strategy, are entirely Vohra’s responsibility. Vaziralli acts as the lead promoter assuming the responsibility of “board stewardship”, focusing on hiring the right talent in the company (which employs over 23,000 people), interacting with the promoters of companies with which Cipla partners for projects, and ensuring Cipla doesn’t lose its “soul and culture” in the process of transformation.

Vaziralli and Vohra review the contours of their working relationship every six to nine months to “stay honest to what they signed up for,” says the latter. The equation appears to be working as many of the operational tweaks envisaged by Vohra and his team receive strong support from Vaziralli. The support is needed to convince the board, which includes YK Hamied and MK Hamied.

Take the case of biosimilars, for instance. Cipla had ambitious plans of making its own biosimilars end-to-end. But that plan has now been shelved. Instead, the company will look for in-licensing partnerships in this space. “We felt there was better resource allocation possible for the capital that we had earlier earmarked for the biosimilars programme,” says Vaziralli.

Cipla’s efforts at transformation have caught the eye of peers as well. “I am impressed with the way the leadership team is shaping up at Cipla. Under Samina and strong professionals like Umang, the team has turned Cipla around and set it on a strong growth path,” says Nilesh Gupta, managing director of Lupin. “Samina’s clarity of vision and belief in professionals sets the path for greatness.”

Vohra says the fact that Vaziralli wasn’t involved with the family’s pharmaceuticals business earlier is a blessing in disguise. “The fact that she hasn’t been with the company for too long makes her braver to take decisions,” he says. “We have made some tough calls over the last two years and it takes someone to be a little emotionally distant from the legacy of the last 82 years to be able to support them.”

For Vaziralli, her tryst with Cipla was her tryst with destiny; something she hadn’t planned for. After finishing her studies, Vaziralli was working with Goldman Sachs in the US as an investment banker. She relocated to India with her husband Rohan when he was tasked with setting up global cosmetics brand Estée Lauder’s India operations. After moving to India, Vaziralli had two sons (now aged 11 and seven) and was on a break from work. When she decided to start working again, her father and uncle suggested that she join Cipla. In 2011, Amar Lulla, Cipla’s former joint MD, had just passed away and there was a big void in the company. “They [YK Hamied and MK Hamied] decided to take a step back and professionalise the company. It was at this point that they entrusted me to take the company’s legacy forward.” At Cipla, Vaziralli began by assuming charge as the global head of strategy and M&A and leading the incubation of the consumer health care business. Had things gone as per the original plan, it would have been her younger brother Kamil Hamied who would have got the top job at the company. But in 2015, Kamil decided to quit Cipla to become a venture capitalist. “Was I prepared for it [the current role]? No. But that is the way of the world. That’s why I have focussed on building a very strong, experienced management team and a board at Cipla that I can rely on,” says Vaziralli.

“Samina plays an important role of being the bridge between the professional management of the company and the board, as well as between the promoters and the board,” says Adil Zainulbhai, an independent director on the board of Cipla (he is also the chairman of Network 18, publisher of Forbes India). “She has really stepped up during the transition of executive responsibilities at Cipla from the older generation to the current one.”

There are “healthy arguments and debates” between Vohra, Vaziralli, her father and uncle about what’s best for Cipla. But the promoters see the light of reason when suggestions are rooted in logic and backed by data, says Vohra. And if the seniors are still not convinced, their views logically carry a “fairly significant amount of weight”, he adds.

The old guard too has warmed up to their successors. “Samina has exceeded all our expectations. She has grown into the role. Not only does she understand Cipla and its people well but also the industry,” says MK Hamied. “Regarding Cipla’s future, we have to keep up with the times.” YK Hamied says his niece has done well to develop not only a robust leadership at Cipla but also a competent second line of management.

For the Hamieds, treading a middle path between business expansion and profitability on the one hand— and serving a humanitarian cause on the other—is an imperative. “If you are in health care, you cannot look at it as a hard and fast business. You have to have a humanitarian approach,” says YK Hamied.

This is something that Vaziralli is mindful of, as evident from Cipla’s recent tie-up with the American Cancer Society and the Clinton Health Access Initiative to expand access to essential cancer treatment across various African nations. It has also set up a palliative care facility for terminally ill patients in Pune.

Vaziralli says multitasking and patience are the two biggest lessons that motherhood has taught her. Given the future path that she has set for herself, these virtues are bound to come in handy.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)