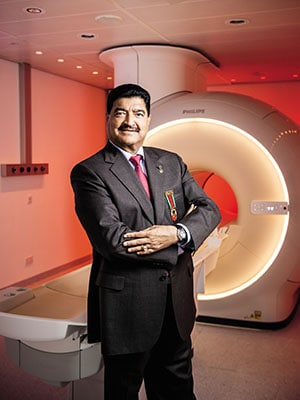

BR Shetty: Building A Health Care Empire

Like many struggling Indians, young BR Shetty went looking for a payday in the Emirates. Drawing on people like himself, he surely found one

BR Shetty

MD and CEO, NMC Health

Age: 71

Rank in the Rich List: 72

Net Worth: $880 million

Key Achievements: Grew NMC into UAE’s largest integrated private health care provider, raising $187 million through an LSE listing in 2012; set up money remitter UAE Exchange for Indians living in the Gulf

Way Forward: NMC looks to open four new facilities, and is scouting for locations in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Oman

Inspiring as BR Shetty’s road to riches story is, it’s not entirely unusual for Indian entrepreneurism: Young man sets out with nothing, starts at street-level selling and remarkably pieces together a billion-dollar fortune—all the while employing his countrymen and providing them with medical services, money transfers and consumer goods. Except for this: Shetty has done it in the United Arab Emirates.

When the strapping, jovial Bavaguthu Raghuram Shetty arrived in underdeveloped Abu Dhabi in 1973, he had $8 in his wallet and a load of debt—but unlimited ambition and some silly pride. The debt was a bank loan in his native Udupi to pay for a sister’s wedding. In the fledgling Emirates, where an oil boom heralded opportunities, his training back home in pharmacy could only get him a job peddling a licenced druggist’s excess stock.

“In a vast, sandy desert, in the middle of a searing hot summer, I became the country’s first outdoor salesman,” 71-year-old Shetty recalls.

His first ‘office’ was his bedroom and his first ‘worktable’ a 150-dirham ($40) Samsonite bag that he preserves. Going from clinic to clinic selling drugs to doctors, loading cartons, hoisting 5-gallon barrels on his shoulder up staircases were all in a day’s work. His 500-dirham ($135) monthly salary afforded a room shared with five other workers. Meantime, too proud to say otherwise, he wrote letters home fabricating a life of luxury.

Today, he has that life. His NMC Health has grown into the region’s largest integrated private health care provider, last year raising $187 million through a London Stock Exchange listing—an Abu Dhabi first.

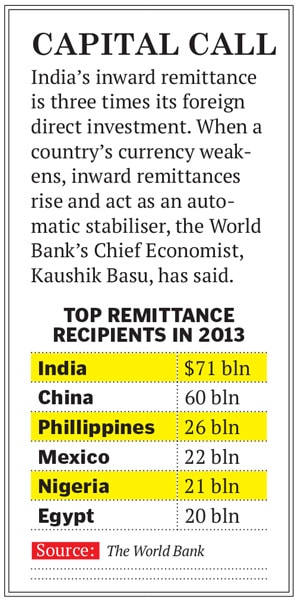

To help expatriate workers transfer money home, he launched a remittance service, UAE Exchange, whose 700 offices in 31 countries transacted $22.5 billion in 2012, making it a top player with 6 percent of the global market and accounting for 10 percent of India’s foreign inward remittances at a time when it desperately needs foreign exchange. His Neopharma contract-manufactures for global drugmakers, one of many Shetty diversifications. Forbes Asia figures his net worth is $880 million.

“It hit me recently that I came to the Middle East as a single man in search of a job and stayed on to build businesses that employ 38,000 people today,” he says with some emotion in an interview at his exceptional pied-à-terre, which spans the entire 100th floor of Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest skyscraper.

If it was the professional Indians’ ambition to go to London or New York, Shetty’s life epitomises working-class India’s Gulf Dream. A boy who once walked barefoot to a village school with fishermen’s children today sports a 4-carat diamond on his finger, diamond-studded Harry Winston and Cartier watches, and is one of the richest Indians in the Middle East.

NMC Health grew out of salesman Shetty noticing how deficient his new terrain was for basic clinics. Yet the first president of the UAE, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, wanted quality, affordable health care for all. Inspired, Shetty set up the New Medical Centre—actually a small pharmacy-cum-diagnostic clinic—in 1975 with 15,000 dirham ($4,000) in capital. It grew into a multispecialty hospital and spawned satellite units across the country. Today, it caters to 5,000 patients daily, with doctors of 42 nationalities, a majority of whom are US- and UK-trained and of Indian origin.

It was serendipitous that Shetty launched into the Gulf oil boom. His growing centre was the first in the region to offer an onshore decompression chamber for unfortunate oil company divers.

He also tended to care offshore. “I was the standby ambulance driver to rush heart attack patients from the oil rigs to my hospital,” he remembers. The Iran-Iraq and Iraq-Kuwait wars brought in more business.

Until Shetty installed a CT scanner, patients in the region had to travel overseas for scans. Today, the centre’s first doctor, Shetty’s wife, Chandrakumari, whom he married in 1976, oversees the eight-hospital chain. Four more are in the pipeline, including a 100-bed maternity hospital, the Emirates’ first private one. The chain is also scouting for locations in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Oman.

The pharmacy chain attached to the hospitals spawned an NMC Health division that is a distributor for drugmakers like Aventis and Merck, and is among the top three trading companies in the UAE, with 65,000 products. It handles not just scientific and medical equipment but also grain and spices from India, and frozen lamb and beef from the US and Australia.

By 2012, NMC Health was more than ready for the City of London. “We had been profitable for 36 straight years since our inception, so listing was a logical step,” Shetty says. The offering will fund the hospital expansion. Profits are up 17.3 percent in the first two quarters of 2013 on sales of $273 million. Shares have risen from the listing price of $3.21 to $5.46.

Back in the 1970s, as his medical operation began to thrive, Shetty saw many Indian expatriates lining up in front of banks for hours to send hard-earned cash back home, often to remote villages. In response, he launched money remitter UAE Exchange with a single branch in Abu Dhabi in 1980. Its network expanded fast as 500 to 600 people thronged there daily on hearing that it charged far less (5 dirham per transfer) than the banks and was speedier.

Today, the UAE Exchange spans the region but has nearly half its transfers going to India. (An estimated 6 million Indians live in the Gulf.) The ticket size of the remittances is small, averaging $200 to $300. “Eighty percent of our customers are blue-collar workers, immigrants who live the single life and diligently send money back home every month,” says Shetty, sitting in his Abu Dhabi office, whose walls include an inaugural Order of Abu Dhabi, the highest civilian award (he also wears the honour as a pin and ribbon), and a matching Padma Shri from India.

“Shetty has achieved amazing success through intuition and hard work,” says Bangalore’s Biocon chief, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, who knows him closely and has done business with him. “His business sense sets him apart.”

In Dubai, customers like Nirmal Thakur, 56, a civil foreman from Himachal Pradesh, and Karla Jobero, a nail technician from Cebu in the Philippines, use the service to repatriate their earnings back home. “It is a blessing that the money reaches my wife on time; she can pay my son’s college fees and run the house,” says Thakur, who has used the service for over a decade.

The Exchange charges a fat $4 for same-day electronic credit. It competes with Western Union, which earlier offered Shetty a buyout. What’s more, over 2,500 companies in the region route the monthly salary disbursals of 1.8 million workers through the UAE Exchange under the government’s programme to ensure that workers, especially in construction, get paid on time.

Adding a foreign exchange (buying and selling currency) turnover of $24 billion, its total 2012 take came to $47 billion in 2012, and profits were $50 million.

With a million daily customers, the Exchange can claim to hand 10 percent of India’s world-leading remittances. The service has stayed relevant with technology, says Sudhir Shetty (no relation), chief operating officer at UAE Exchange.

“What used to be a manual, three-week-long transfer in the 1990s is instantaneous today, taking away the anxiety of those who send money to pay hospital bills, school fees or other time-bound expenses,” he says.

NMC Health, meanwhile, is exploring a partnership with an Ivy League university for a medical college in Abu Dhabi and looking at setting up a postgraduate programme in Dubai. A potential tie-up with another leading American academic brand could lead to an entrepreneurship school. Says Shetty, “I want to give back to the country that gave me everything I have today.”

He says this spirit led him to buy the Burj Khalifa pad though he is not a “real estate man”.

“The country’s leadership was promoting a project, and it was my earnest duty to support it.” He confesses, however, to a weakness for grand cars. He owns a fleet of seven Rolls-Royces and a Maybach beneath his main home in Abu Dhabi. He lovingly tends to each and says he cannot bring himself to sell any. “People tell me that I should not be seen driving around in these as it generates envy,” he says gesturing to his Rolls-Royce Phantom. “But this is my solitary pleasure in life.”

Well, maybe cricket, too: He was instrumental in building a stadium in Abu Dhabi. “I don’t even watch films; my life is entertaining enough,” he says. Of Shetty’s four children, two are in the business. Son Binay, 30, was the first baby to be delivered in an NMC Hospital and is now chief operating officer of NMC Health. The youngest daughter, Seema, is a director of UAE Exchange and runs a diet-food chain called BiteRite.

Having that support, plus long-time retainers—Maharukh Khambatta has managed his office for 34 years, and his chauffeur, Dawood, has driven him for 24—gives Shetty spare bandwidth to look outwards. He is on a personal overseas buying spree with two hospitals in Alexandria, Egypt, in which he holds a 90 percent stake, and a third in Cairo. In Kathmandu, Nepal he holds 51 percent of a medical college hospital that will open next year. He is exploring hospital management in Sri Lanka.

Says Shetty’s compatriot, Middle East retail billionaire MA Yusuff Ali, “Like me, he came with nothing. We have all grown through hard work.”

And now Shetty’s life is coming back around to India. He has acquired a 220-bed hospital at Thiruvananthapuram in southern Kerala and is doubling its capacity. In central Raipur, he has acquired a majority stake in an orthopaedics hospital. “I want to expand across India and serve Indians.” The plan is to offer affordable health care in smaller cities and create a 12,000-bed hospital infrastructure in five years, he says.

In the meantime, he wants UAE Exchange’s 330 branches in India expanded to 850 in the next couple of years, mostly in very rural areas. Shetty is one of 26 in line for new banking franchises, alongside Indian mainstays like Tata, Ambani and Birla. Banking would extend his money-transfer experience, working at the bottom of the income pyramid. “Nothing would give me greater satisfaction than bringing the poorest Indians into the organised financial system.” And keeping more of them well.

GunnySacks with dollars

br shetty has branched off from his core operations in unusual directions “out of necessity”, he says. When his patients needed a cafeteria, he launched Foodlands restaurant, which has grown into a six-restaurant chain with a catering division. His staff needed haircuts so he set up his personal hairdresser (who has trimmed his hair for 30-plus years) with a barber shop. His hospital needed well-sterilised sheets so he started a Laundromat.

Most of all, the chain needed quality drugs at good value so he set up a manufacturing company, Neopharma, and then initiated a backward integration by contract pillmaking for companies such as Merck. When the company was allotted barren desert land, bankers withdrew from the project, but Shetty roped in an Indian bank, Bank of Baroda. Neopharma’s gleaming $30 million plant sits in a green oasis and is the top generic drugmaker in the UAE.

Other businesses are small but growing and include a maintenance company called Guide; consumer products maker Neocare; the New Oil Field Services, which provides manpower and equipment to oilfelds; a school chain called Bright Riders; and hotel chain Lotus. The catering company Foodlands was commissioned during the Gulf War to cater to American airmen. “For months we supplied chicken breast sandwiches for lunch and hamburger dinners to 2,000 airmen at the Al Dhafra airbase at $60 per head,” recalls Shetty. The payment came via gunnysacks stuffed with dollars.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)