Family Businesses And Splitting Heirs

India’s storied business families are becoming more professional as they gear up for generational change

Dead men tell no tales but on July 4, 2004, things were a bit different. Priyamvada Birla, widow of Madhav Prasad Birla, had died. Madhav Prasad Birla was one of the four Birla brothers who built the Birla Empire. Priyamvada’s will had the Birlas stumped. She had given away her wealth to her chartered accountant, R.S. Lodha. That gift also included her share in Pilani Investments. This company has often been described, innocuously it would seem, as an investment company. The reality is that it was how the Birla Empire’s economic interests were aligned between family members. Through a maze of cross-holdings that ran across companies in the MP, BK, and AV Birla Group, wealth was kept within the family. It had never occurred to the family that this way of apportioning wealth would have a downside. And then R.S. Lodha, an outsider to the family, was suddenly pitch forked into Pilani Investments. The Birlas swore to keep him out. It was only later that they realised that this model of managing family wealth had outlived its purpose. It took them five years to unravel the fabric of cross-holdings.

If the Birla episode was a wake-up call for other Indian business families, the Ambani family feud got them to smell the coffee. “After that episode most Indian business families started thinking very seriously about having a roadmap for one, accommodating family members inside business and two, entry of sons and daughters into the business,” says Salil Bhandari, managing partner, BGJC, a Delhi-based consulting firm. Indian business families are different from those in the West. In India, most business families are part of the old joint family system. It takes professionals working with these enterprises years before they figure out key decision makers within the family. That’s how amorphous it can get. “It’s a reflection of society. There is a lot of support mechanism — from the family, relatives; this network of people. Brothers fight here too, but this broader system makes sure that trivial issues do not lead to a break up of relationships,” says Kavil Ramachandran, Thomas Schmidheiny Chair Professor of Family Business and Wealth Management, Indian School of Business.

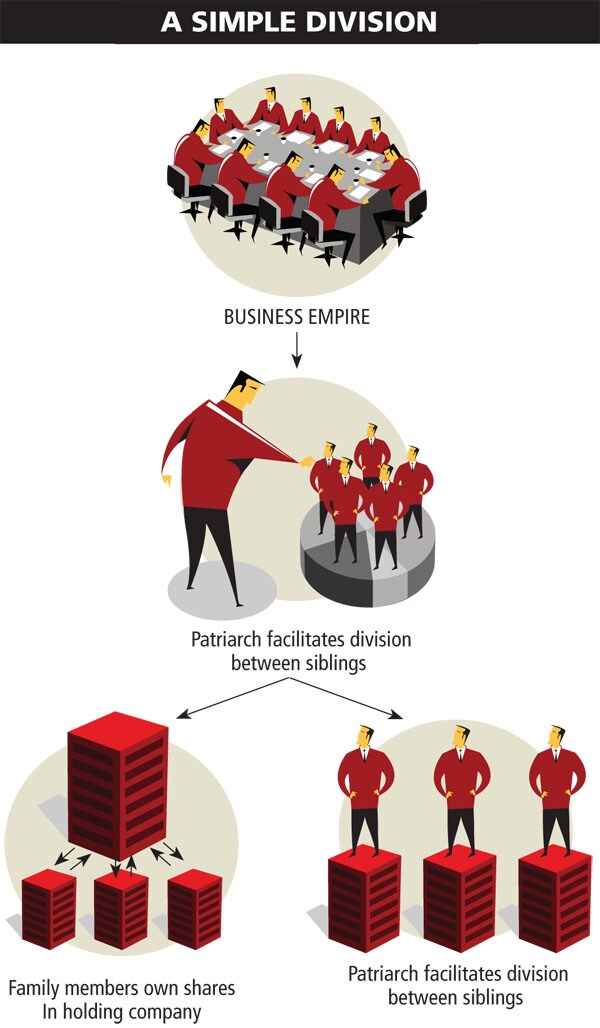

Global research shows that most business families can’t keep their flock together for more than three generations. Ramachandran says that for India, no clear data exists but there is anecdotal evidence. The Birlas split after three generations, the Ambanis in the second generation, and the Bajajs in the third generation. The Jindals have divided the business empire operationally; though the control of the company is centralised in the hands of Savitri Jindal.

No wonder then that Indian business families are eager to avoid a script-less family drama. They would much rather plan for the involvement of members in advance. “There is value destruction when the news of a split catches the markets by surprise,” says P.M. Kumar, a family advisor of the Bangalore-based infrastructure company GMR, which has been in the news for putting together a family constitution. Kumar is now member of the GMR group holding board.

When Anil Ambani made his impassionate plea about ownership issues at the Reliance AGM on August 3, 2005, Reliance Industries stock fell from Rs. 760 to Rs. 710 before recovering somewhat. Even the Sensex dropped 80 points that day on this development. This is a defensive reason at the best. A more important factor is that most business groups are fighting a war for talent. Family members can be valuable resources for the group to tap. “Indian business houses are competing with MNCs for talent. Family members, if properly groomed, can be a source of advantage in their understanding and also commitment to the business,” says John Ward, Clinical Professor of Family Enterprise & Co-Director of the Center for Family Enterprises, Kellogg School of Management. The second key reason is that the members of the next generation know their place in the enterprise. This prevents nasty surprises — for family members as well as investors.

Counter-intuitive as it may sound, Indian families are involving the younger members of the family right at the start of the discussion. The younger lot is more educated and open to concepts. The older generation is often caught in situations where respect means saying nothing. Even when they see something they don’t agree with, they say nothing. So the next generation must be involved. They are anyway the people who will have to execute the plan and must be convinced, otherwise it won’t work. If the participants are not agreeable to the plan, then even if it’s a legal document, nobody will act on it.

There is this business group — a patriarch and his brother, and their kids and grandkids. They all got into a room to start discussing succession planning. Now between the brothers, all in their forties, there was a lot of argument and it went into a deadlock. So a family advisor came up with a suggestion: Let the younger generation—their children, all in their 20s — go away together to attend a one-week course on succession planning. At the end of that exercise, they would have to draw up a transition plan for the family. So at the end of that course, they all sat down and prepared a plan — a PowerPoint presentation for the rest of the family. At the end of presentation, the elder generation was speechless. The youngest generation had come up with a fantastic solution and so the elders said they would do it.

The other major shift that business families are trying to make is to include their daughters as well in the succession and discussion plan. Till now, daughters have been by and large ignored. Take for instance a large NRI family, which had a huge succession planning challenge. There were 10-15 children, two brothers, 11-12 sons and many cousins. “We asked them how many daughters did they have. They promptly told us, we don’t want to talk about our daughters,” says Richa Karpe, director, investments at Altamount Capital, an agency that specialises in wealth transfer planning. The group members were told that there was little point in planning a succession because it was clear that only sons were being considered. “They had a very talented set of daughters. They had all studied in Ivy league colleges but they were not being considered at all. It is very important to bring the daughters into the equation,” says Karpe.

Including daughters is a welcome change. Kellogg School’s Ward believes that Indian business groups are particularly prone to splitting because they don’t involve daughters in their family business. “A family that only has brothers at the helm is the most unstable form of business enterprise. Brothers often end up with ego issues. If you involve daughters and other members then the bond is stronger,” he says. This stands to reason. It is criminal to not deploy 50 percent of the talent in a business family. “If Indra Nooyi can run Pepsico, If ICICI and UBS can be run by women, why not a family business?” asks Parimal Merchant, professor, SP Jain Institute of Management and Research.

The Godrej group is a good example. Adi Godrej’s two daughters, Tanya Dubash and Nisa, are both playing an active role in the group. Ajay Piramal’s daughter Nandini played a very active role in Abbott’s purchase of Piramal’s generics business. She is assisting Ajay Piramal into their foray into realty among other new ventures that they have planned.

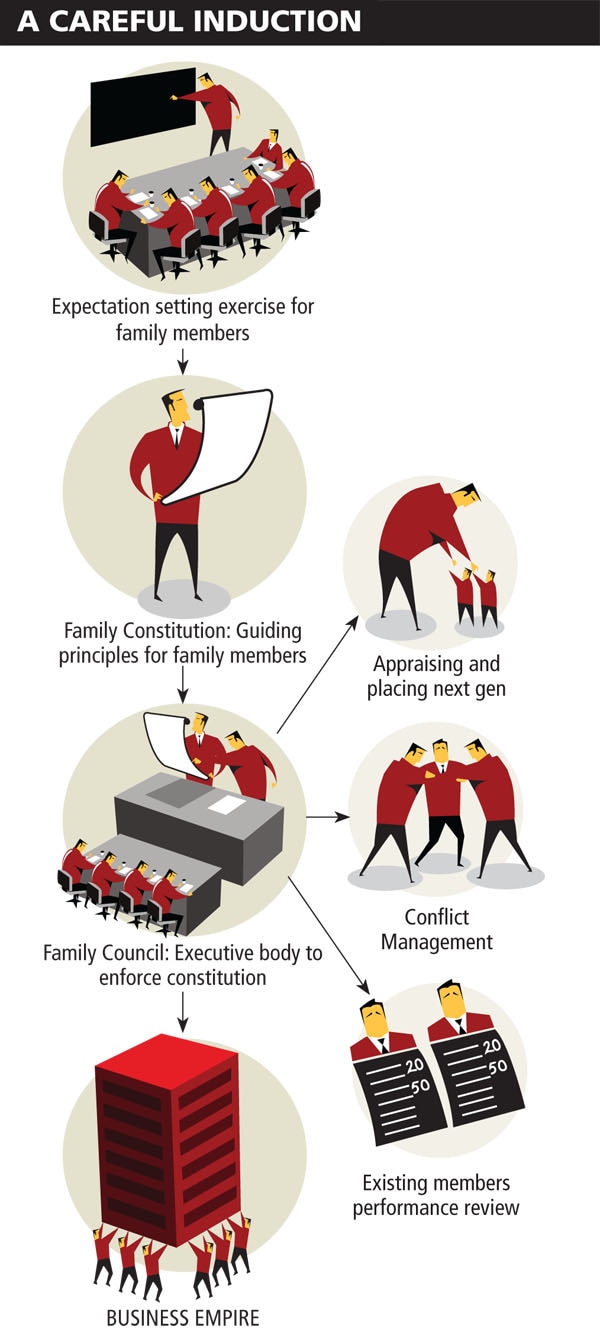

Perhaps the most critical aspect of getting the family involved is the blueprint required to get the entire family to understand the exercise. Broadly, there are two models of doing this (see graphics). The first approach believes that it is indeed possible to harmonise expectations inside the family before any blueprint is made. The second approach is about dividing the empire. The first model is far more difficult, but is finding acceptance on a larger basis because an undivided group has more resources, a bigger balance sheet and hence a bigger impact in the market place. Though the pioneers here are the Murugappa group, it is GMR, the infrastructure heavyweight, that has really taken this to a new level.

It has a family constitution that is the “book” to which members must refer for dos and don’ts.

The most interesting aspect of GMR’s approach was actually to get all the family members away on a retreat. The key message sent out at the retreat was that before handling family wealth, each one of them would have to understand relationships within the group. Spouses were taken on board and were explained how their husbands and sons could be picked for a role inside the organisation. They were told the logic behind these choices. “Spouses influence the male members’ thinking tremendously,” says Kumar, who worked out their

transition plan.

All family members were also advised to bring their living standards within a commonly accepted band. “A lot of resentment can be traced back to the fact that one segment in the family may have an extravagant lifestyle while the other may be more down to earth. Family members also decide what sort of schools children will attend,” says Kumar. That might appear intrusive but this sort of thing makes sure that the family members have a similar world view and value systems.

Perhaps the most critical matter before most business families is the way they introduce their sons or daughters into the business. Twenty years ago, this was not such a big issue. India still believed in God-given rights! Today’s employees are different. They have been brought up on a diet of meritocracy. If top professionals feel they will not have room to grow because the scion of the business family and his cousins will grab all the top spots, then there is sure to be a talent flight. Most business groups are very careful about how they do this.

GMR uses the results from an “aptitude test” and a host of other criteria like education and inclination to come up with a right place inside the organisation for the youngster who wants to join the family business.

The Murugappa Group insists on outside work experience. “We try to see that each of them work outside and gain experience for a minimum period of three years,” says A. Vellayan, executive chairman, Murugappa Group. After entering the business, the member works in one area for four-five years and then also works in other businesses by rotation so that he can understand his aptitude and strengths. He has the same kind of objectives and KRAs set out for him as other non-family professionals. His performance is measured in a similar way too.

At Wipro, things are a bit different. It is widely understood in Wipro that Rishad Premji will take his father’s position, simply because his father owns 80 percent of the company. However, it doesn’t bother people too much in the organisation, because they see the difference between ownership and management. Although Premji is the final authority on everything, he doesn’t run Wipro like a family firm. He has put in place elaborate processes and checks for taking large decisions and he is a stickler for rules. So, large strategic decisions are taken collaboratively. People often disagree with Premji and he allows that. So in their minds, they are clear that the same culture will continue at Wipro.

“One key issue is that Indian family members want to remain involved with the operations of the companies in their group,” says Ward. In the West, many families, like the Wallenbergs who control ABB through a holding company AB, prefer not to get involved in operations. “In India you need to have operational control. It determines social standing,” says Jyotirmoy Bose, founder and chief executive, White Spaces Consulting, a company which advises midcaps on such transition issues. This is not a bad thing, but business groups realise the need for making this transparent to non-family professionals. At GMR, every family member who is in the group has an annual goal-sheet. At the end of the year, group chairman G.M. Rao conducts a performance review. “It is a very frank discussion. At the end of the discussion you come to know if you have done your job well,” says Kumar. The additional benefit of such an exercise is that the professionals in the group believe that the entire system is based on meritocracy and accountability.

This is important because at some point if a business group remains undivided, family members might concentrate on playing the role of an active investor in the holding company, rather than an operating manager. When that happens they will need top quality management to run the company and deliver returns to shareholders. “It is important for family members to realise this because many professionals today want to work for family businesses. They feel that such groups have a longer view of the business. They like the values and culture of a family business. This is a huge plus,” says Ward.

This might be some time away in India given the dynamic nature of the market, but it will happen and those groups that have prepared well will see their companies thrive even if the family members don’t run it on a daily basis. Those groups may even last beyond the three generations’ natural limit!

(Additional reporting by Mitu Jayashankar)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)