Kapil Sibal Shifts the Onus of Education to the Government

Kapil Sibal’s education bill is ambitious. But he has to convince the states

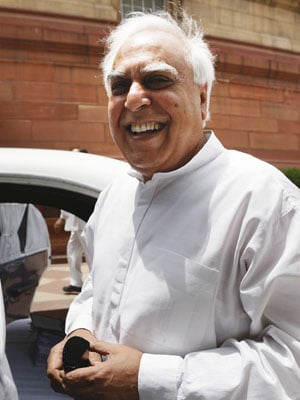

Kapil sibal

Budget Allocation : Rs. 31,036 crore for school education. Most of this will go to RTE implementation (RTE will require an expenditure of Rs. 1,72,000 crore over the next five years)

Big Idea

Education becomes a Fundamental Right. It’s the government’s responsibility to ensure that children within the age group 6-14 get good quality education

Long-term Goals

Lift standards. Implement basic norms for infrastructure, teacher-student ratio etc. Schools will be derecognised if they don’t comply

In 1893, the king of Baroda, Maharaja Sayajirao III, implemented compulsory primary education in a small taluka in Amralli district. In this nine-village cluster, children from the ages of seven to 12 were educated. This tiny experiment was a roaring success and was extended to all 52 villages in the district. Eventually, compulsory primary education was extended to the entire state. This was India’s first recorded stab at compulsory education.

Today Union Minister of Human Resource Development Kapil Sibal is trying to replicate the Maharaja’s endeavour through the Right to Education (RTE) Bill. While the RTE Bill was passed in 2002, it is being notified only on April 1 this year. Sibal was also the chairman of the Drafting Committee when the Bill was being formulated during the then HRD Minister Arjun Singh’s time.

Miles To Go

Ever since he took charge of the ministry, Sibal has been trying to engineer radical changes in the sector. “All these years, education was about politics and not reform. I give full credit to Sibal for pushing through reforms and not politicising education,” says Madhav Chavan, founder and CEO of the

educational non-profit organisation Pratham.

The Bill has the potential to change the way education is viewed in India. Education will become a fundamental right for all children aged between six and 14. RTE will require Rs. 1,72,000 crore over the next five years. R. Govinda, vice-chancellor, National University of Educational Planning and Administration, who was also on the Drafting Committee says, “RTE will change the nature of discourse. Till now whatever we have done through the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan or other initiatives have been projects that require inputs for improving the school system. Now education has become the fundamental right so it becomes the entitlement of every child.” It is the government’s responsibility of getting children within the target group into schools. This will be legally enforceable and one can go to court against the government if denied education.

Initiatives such as the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan have successfully put a lot of children into school. Estimates suggest that in 2001, 5 crore out of 21 crore children were out of school. Today that figure stands at a considerably lower 30-40 lakh. “State governments have done a lot for education,” says Amit Kaushik, COO, Pratham. “The first step is access but now we need to move on to the next milestone: When you set up schools, what happens then?” he asks. Kaushik was a director in the HRD ministry before joining Pratham.

So far, it is not a very happy picture. Consider the following statistics from Pratham’s Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) report: Only 50.3 percent of standard V students in government schools were able to read Standard II level text. Only 36.1 percent students were able to correctly solve a basic division problem.

The RTE has put in place a series of measures that not only aim to attack the problem of access, but also lift quality. Accessible schools within walking distance must be established. RTE mandates 25 percent reservation for children from weaker sections in Class I of all private schools. On the quality front, RTE has defined strict norms on the student-teacher ratio. So for grades 1-5 the law mandates that the student-teacher ratio will not exceed 40 for schools with more than 200 students. For those with up to 60 students, there should be two teachers at least. For grades 6-8, there should be at least one teacher for every 35 students and here schools need to have separate teachers for science and mathematics, social studies and languages. The minimum number of working days and instructional hours for teachers has been specified.