In honour of TS Shanbhag: Books to audio and e-books—the changing contours of publishing value chain

Audio and ebooks have changed the dynamics of the book publishing value chain—with the possibility of doing more with less or the same real estate and working capital, and giving new writers a chance to brush shoulders with bestsellers. What does that mean for booksellers like Shanbhag, and for writers, and readers?

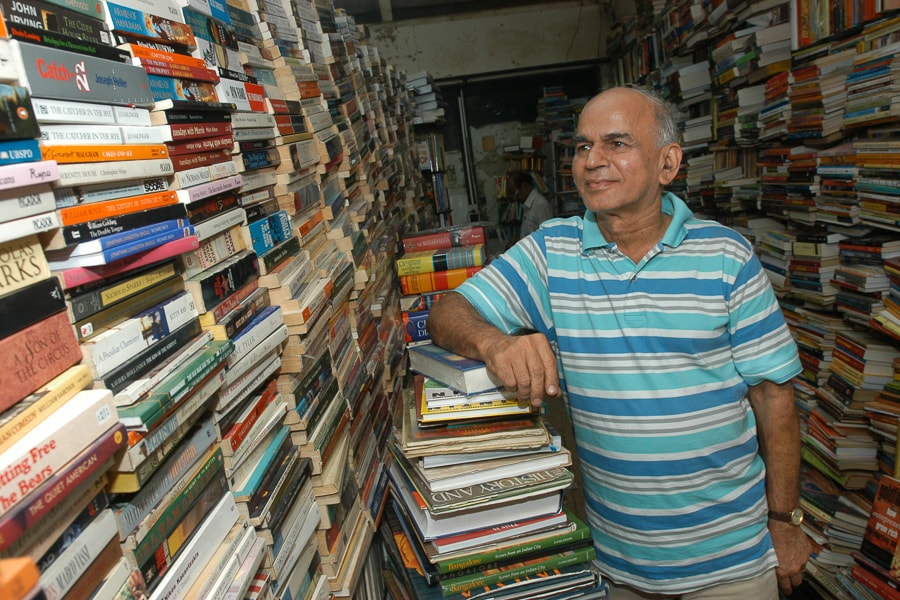

T S Shanbhag, the legendary bookseller at his Premier Book Shop in Church Street in Bangalore

T S Shanbhag, the legendary bookseller at his Premier Book Shop in Church Street in Bangalore

Image: Gireesh Gv / The India Today Group via Getty Images

TS Shanbhag of Premier Book Shop, the legendary bookseller of Bengaluru recently succumbed to Covid-19. Generations of Bengalurians grew up reading books from his shop, which was crammed, chaotic and free for all. Shanbhag would sit behind a pile of books on his table and scrawl a bill when the books were chosen. The bill would have a significant discount—voluntarily given.

Shanbhag was not talkative, but perceptive. He knew the art of providing books, without being intrusive. He provided a better bargain at the cost of his profitability. R Sriram of Crossword bookstores fame once told me why it makes no business sense to give discounts to non-discount seekers. While some customers seek discounts, most valued a curated range of books, personalised service and convenience. When they come to the counter, they would have made up their mind and discount would not change the decision. On a purchase which is impulsive and specific, discounts did not make sense from a business perspective.

[This article has been published with permission from IIM Bangalore. www.iimb.ac.in Views expressed are personal.]