Nature Bio Foods: Growing India's organic food market

On the back of a vertically integrated supply chain, and world-class R&D and manufacturing facilities, the firm is on its way to becoming a global leader in nutraceutical ingredients

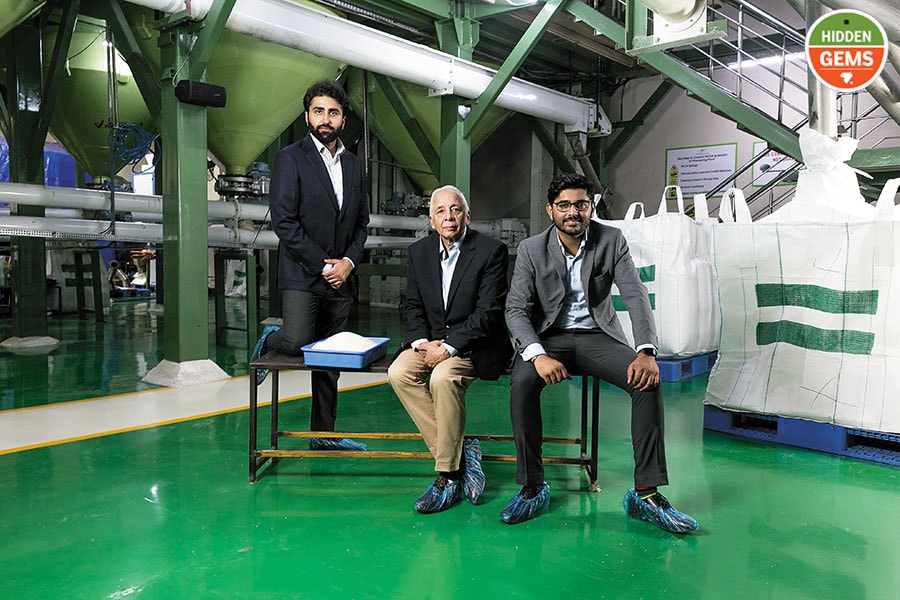

JS Oberoi, CEO of Nature Bio Foods, flanked by directors Anmol Arora (left) and Rohan Grover (right)

JS Oberoi, CEO of Nature Bio Foods, flanked by directors Anmol Arora (left) and Rohan Grover (right)Image: Madhu Kapparath

At their headquarters, on the outskirts of Sonepat in Haryana, the manufacturing facility of Nature Bio Foods looks rather ordinary. Outside, numerous trucks are lined up to ferry the sacks of rice that are being loaded on to them. But inside it’s a different world altogether.

Nobody, including the top management, can even consider going in without full-sleeved jackets, shoe covers, and headgear, and without signing an affidavit stating if visitors have had a fever or any injury in the past few months. Visitors also need to pass through a high-pressure air shower to enter the factory.

“We are very particular about contamination and take every effort to prevent that,” says Rohan Grover, director for global business at Nature Bio Foods. There is good reason for all that vigil. For one, the company claims to account for nearly 75 percent of all organic rice exported from India, a bulk of which is consumed in the US and Europe. “About 99 percent of our business is exports,” he says.

Nature Bio Foods is a subsidiary of LT Foods, which produces the Daawat brand of rice. The company works with nearly 70,000 farmers spread across 14 states and has over 1.1 lakh hectares under cultivation. To put that in perspective, that’s the total land area of Hong Kong.

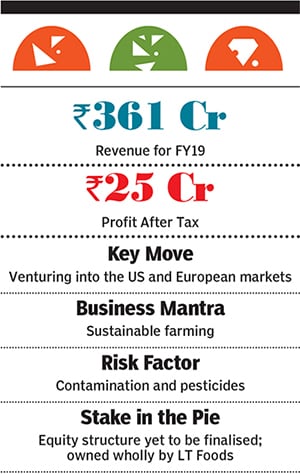

The company has also forayed into growing soybean, flax seeds, chickpeas, red lentils, and amaranth; it says it contributes about 17 percent of all organic food exported from India. Last year, it raised ₹140 crore from Rabo Equity Advisors, a food and agriculture-focussed investment firm.

“We managed to build a reputation that whatever we do is genuine, and there is a real sense of development on the social and economic front for the farmers,” says Grover. Between 2013 and 2018, the company’s compound annual growth rate (CAGR) stood at 45 percent.

The big idea

Nature Bio Foods was set up in 1997 as a subsidiary of LT Foods, which is promoted by Vijay Kumar Arora; it sells over 2.67 lakh tonnes of branded basmati rice annually and is the world’s second-largest rice miller, according to AC Nielsen.

The idea to set up an organic subsidiary came due to the growing demand for organic food in Western countries. Back then, LT Foods, which was set up in 1990, had begun exporting basmati rice to the US and Europe, when a distributor mentioned the potential for organic food. “We were anyway working with the farmers on the sustainability front, and since we had the strength we thought, why don’t we start,” says Grover. “We separated our line of work with a different set of people who are totally into this segment. And that’s how Nature Bio Foods was born.”

Since then, much of the company’s attention was on organic rice, although in recent times it has begun focussing on baby foods and pulses. In India, it sells its products under the Eco Life brand, and expects demand to pick up only in the next few years.

The global organic food market is worth $100 billion (₹7,082 crore), with nearly 50 percent of consumption coming from the US, and 40 percent from Europe. India’s organic products market has been growing at a CAGR of 25 percent and is expected to reach between ₹10,000 crore and ₹12,000 crore by 2020, from the current market size of ₹4,000 crore, according to a report by industry body Assocham and consultancy firm EY. Nature Bio Foods is looking to tap into this market.

But growing organic food in India comes with its share of challenges. There is a shortage of pesticide-free land. There is also the work needed to ensure that the supply chain doesn’t get contaminated. Above all, there is a need for awareness among farmers to adapt to organic farming. “We need to protect the supply chain to avoid cross-contamination,” says Grover.

To begin with, the company sends its employees to scout for locations that have been, by default, practising organic farming. “Unfortunately, farmers in India are very poor and get influenced by anybody who says their yield would increase by using pesticides,” says Grover. “We make them understand the benefits and are fine with the premiums, which vary between 20 and 50 percent.” The company gives them a buyback assurance and also distributes seeds. This year, in all, it distributed about 62 tonnes of seeds, some for free, and in some cases, adjusted against the harvest.

“In the US and Europe, consumers want to know where the product has come from,” says Grover. “So connecting with the farmer is very important. Another factor has been the fair trade movement which started in Europe. So, if a consumer pays a little extra premium because it’s a fair trade channel, that gets passed on to the farmer.”

The focus on the export market means the company faces intense competition from across the world, particularly Argentina and Brazil. “We have managed to build a reputation that when buyers see it is from India, they want to buy it,” says Grover.

“The entire organic industry in India is skewed in favour of a few commodities such as soybean, rice or tea,” says Nitin Puri, senior president, and global head—food, agri strategic advisory and research, Yes Bank. “As far as the domestic certified organic industry is concerned, it has been growing quite fast. But, the challenge always comes from the supply side. Companies that have diversified their portfolio instead of focussing on just one product will be the ones that will grow in future.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)