Nazara Games: Playing to win

With the mobile gaming market in India expected to boom, the Mumbai-based company is ready to reap the benefits

The years following the dotcom crash of 2000 were hard on Nitish Mittersain, the founder of the then freshly minted Mumbai-based gaming company Nazara Technologies (recently rechristened Nazara Games). His venture was building Flash-based multiplayer games, and planned to generate revenues through brand partnerships. But when the crash struck home, it destroyed any possibility of advertising income. The company had raised about Rs 75 lakh from angel investors at a wildly ambitious valuation of over $5 million and, in a short period of time, had hired a workforce of almost 60 people. Nazara had just begun and it was already time to cut back. “It took a couple of years to really get the full realisation of the magnitude of the crash,” says Mittersain, who was only 20 at the time.

By 2004, having scaled back operations and recuperated losses, Nazara and its founder were “back to square one”, or where they were before the bust hit.

The company had, by then, begun working on localised gaming on mobile phones. “We thought: Let’s build a big brand and a big IP [intellectual property] that people will recognise,” he says. And this was the biggest—and most audacious—idea they could possibly come up with: “Let’s make a game with Sachin Tendulkar.”

A few months later, Mittersain found himself in the cricketing icon’s home. A star-struck Mittersain showed Tendulkar a mock-up of the game that his team had put together. “He seemed excited. So I said, boss, I need exclusive rights to make games for you. He said: Okay, I’ll charge you a million dollars. That’s my minimum endorsement fee.”

Even now, Mittersain barely manages to say “one million dollars” between loud guffaws. “I told him I can give you Rs 5 lakh maximum.” He spent some more time with the cricketer, asking him to look at it as a way of connecting with his fans rather than as a commercial venture. “To be fair to him, he [eventually] said, let’s do it.” That, in effect, was the beginning.

The upside of this association—apart from the visibility—was that it provided Mittersain access to telecom giant Airtel, of which Tendulkar was then the brand ambassador. “That’s how I got my first contract with them.” Such deals typically involved the operator selling Nazara’s games to its customers on a revenue-share basis. Other telecom companies suddenly became more accessible.

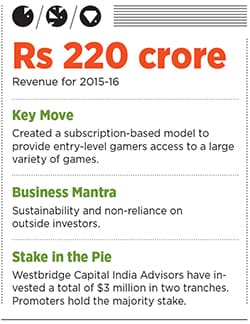

Following this breakthrough, Nazara found an investor in WestBridge Capital India Advisors, which invested $1.5 million in 2005 and another $1.5 million in 2007; this was also the year that Nazara decided to become a mobile-only gaming company, recalls Mittersain, talking to Forbes India in a large boardroom at his company’s offices at Nariman Point in Mumbai. He is sitting on a chair with wheels that he pushes around with his feet, rolling it back and forth as he speaks. Seated beside him is the former CEO of Reliance Games, Manish Agarwal, who took over as CEO from Mittersain, who became managing director, a little over a year ago.

Today, says Mittersain, Nazara Games, in addition to being a mobile games developer, is also a publisher, which involves licensing an IP from its owner and partnering with third-party developers to create a game with it. A publisher typically also works on the game’s design, its monetisation, engagement, virality and data analytics. Chhota Bheem, a mobile game based on the popular animated character, is a good example. Nazara struck a deal with the game’s IP owner, Green Gold Animation, in 2015, proceeded to engage third-party developers to create it and, thereafter, distributed it through various channels.

The person behind it

Very early in our conversation, it becomes clear that gaming wasn’t just a sudden fancy for Mittersain. “I coded my first game when I was 8 years old,” he points out. This explains his youth at the time of launching Nazara. (His father, Vikash Mittersain, who ran a textile business, was the first angel investor in his son’s company, and holds the position of chairman in Nazara.)

In the heady days of the dotcom bubble, Mittersain recalls being courted by several investors, for “crazy valuations”. In the sobering period that followed, he decided to adopt an approach that he continues to stay true to even today.

“I promised myself that we’ll build a business that is sustainable on its own. Not dependent on any VC or investor.”

Why it is a Gem

This approach has resulted in a company that has relied almost exclusively on organic growth. “The business has always generated enough cash. I think we invested to get it off the ground, but it is self-sustaining,” says Sanjeev Mehra, vice president at WestBridge Capital India Advisors.

An inflection point in Nazara’s journey came in 2010. “We saw that a lot of our users [who purchased games directly] were college students, who had a limited amount of money. They would download two or three games, pay for them and then drop off,” says Mittersain. The solution to this problem came in the form of Nazara Games Club, a subscription-based platform that allows users to choose from a variety of games they can play on it. It proved to be the perfect product for new users who were entering the fold.

“It took our company from the Rs 3-4 crore level [in revenues] to Rs 100 crore in about three years,” says Mittersain. And its golden run has continued. In FY2016, the company claims to have generated Rs 220 crore in revenues. In the same year, it clocked 35 million visitors, over 16 million in FY15.

Mittersain says that the company has been profitable since 2008. In fact, with the cash reserves that it has built up over time, it has even created a gaming fund, Nazara Game Fund, to invest in developers both in India and abroad.

Its sustainable business approach puts it in an enviable position, considering the pace at which mobile gaming is expected to grow in the near future. A Ficci-KPMG report, published this March, suggests that the mobile gaming market in India will expand from $200 million in 2016 to $3 billion in 2019.

The company, meanwhile, has continued with its approach of signing up recognisable faces, ranging from cricketers (Virat Kohli) to Bollywood stars (Hrithik Roshan) and cartoon franchises for its IPs. Recently, it also struck a publishing deal for the hugely popular mobile game, Cut the Rope, with Moscow-based Zeptolabs. “We believe gaming is going to take off. If there are 100 million mobile gamers today, there will be 300 million in five years,” says Agarwal, Nazara’s CEO.

He adds that its subscription model, geared towards first-time users, as well as its push for the app-based freemium model, aimed at more seasoned gamers, will be the “twin engines of growth”. With its suite of products, Nazara is already present in about 50 countries, across Asia and Africa.

Risks and challenges

In mobile gaming, like in any other entertainment business, each project brings with it a high probability of success and failure. There are infrastructural challenges too. The micro-payments ecosystem in India is still not good enough to enable users to easily transact within the game. In-app purchases, then, are limited.

For new users entering the gaming world, the habit of playing multiplayer, competitive games may still take some time to develop.

However, with 30.7 million smartphones being shipped into India in the second quarter of 2016 alone, there is little doubt about the future of mobile gaming. People will play.

“All you have to do is convert that habit of playing to paying,” says Agarwal.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)