Skills and behaviors that make entrepreneurs successful

Research at Harvard Business School by Lynda Applegate, Janet Kraus, and Timothy Butler takes a unique approach to understanding behaviors and skills associated with successful entrepreneurs

What makes a successful entrepreneurial leader?

Is it the technical brilliance of Bill Gates? The obsessive focus on user experience of Steve Jobs? The vision, passion, and strong execution of Care.com’s Sheila Lirio Marcelo? Or maybe it’s about previous experience, education, or life circumstances that increase confidence in a person’s entrepreneurial abilities.

Like the conviction of Marla Malcolm Beck and husband Barry Beck that high-end beauty retail stores and spas, tightly coupled with online stores, was the business model of the future, while other entrepreneurs—and the investors who financed them—declared such brick-and-mortar businesses were dinosaurs on their way to extinction. The success of Bluemercury proved the critics wrong.

Despite much research into explaining what makes entrepreneurial leaders tick, the answers are far from clear. In fact, most studies present conflicting findings. Entrepreneurs, it seems, are still very much a black box waiting to be opened.

A Harvard Business School research team is hoping that a new approach will enable better understanding of the entrepreneurial leader. The program combines self-assessments of their skills and behaviors by entrepreneurs themselves with evaluations of them by peers, friends, and employees.

Along the way the data is also allowing scholars to study attributes of entrepreneurs by gender, as well compare serial entrepreneurs versus first-time founders.

“We’ve always had a hard time being able to identify the skills and behaviors of entrepreneurial leaders,” says HBS Professor Lynda Applegate, who has spent 20 years studying leadership approaches and behaviors of successful entrepreneurs. “Part of the problem is that people usually focus on an entrepreneurial ‘personality’ rather than identifying the unique skills and behaviors of entrepreneurs who launch and grow their own firms.”

Complicating this understanding are the many types of entrepreneurial ventures that exist, says Applegate. These can include small “lifestyle” businesses, multi-generational family businesses, high-growth, venture funded technology businesses, and new ventures designed to commercialize breakthrough discoveries in life sciences, clean tech, and other scientific fields.

“These types of ventures seem to both appeal to and require different types of entrepreneurial leaders and we are hoping that our research will help us understand those differences—if they exist,” says Applegate, the Sarofim-Rock Professor of Business Administration at HBS and Chair of the HBS Executive Education Portfolio for Business Owners & Entrepreneurs.

The answers are already starting to come in, thanks to initial results from a pilot test of “The Entrepreneurial Leader: Self Assessment” survey taken by 1,300 HBS alumni. Results allowed the researchers to refine the self-assessment and to create a second survey, “The Entrepreneurial Leader: Peer Assessment.” Both are being prepared for launch in summer 2016.

The team included Applegate; Janet Kraus, entrepreneur-in-residence; and Tim Butler, Senior Fellow and Senior Advisor to Career and Professional Development at HBS and Chief Scientist and co-founder of Career Leader.

Dimensions of entrepreneurial leadership

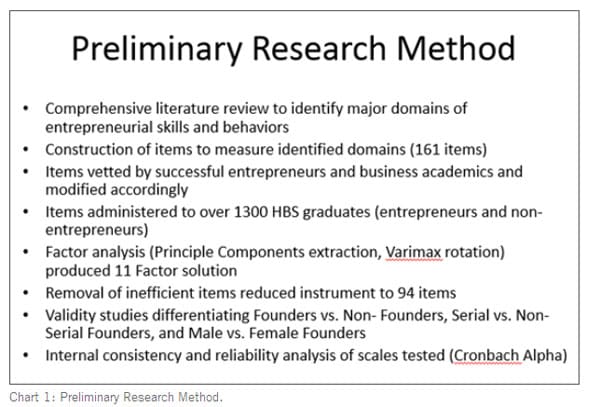

A literature review combined with interviews of successful entrepreneurs helped the team define key factors that formed the foundation for the self-assessment. These dimensions were further refined based on statistical analysis of the pilot test responses to create a new survey instrument that defines 11 factors and associated survey questions that will be used to understand the level of comfort and self-confidence that founders and non-founders have with various dimensions of entrepreneurial leadership (Chart 1).

These 11 dimensions are:

- Identification of Opportunities. Measures skills and behaviors associated with the ability to identify and seek out high-potential business opportunities.

- Vision and Influence. Measures skills and behaviors associated with the ability to influence all internal and external stakeholders that must work together to execute a business vision and strategy.

- Comfort with Uncertainty. Measures skills and behaviors associated with being able to move a business agenda forward in the face of uncertain and ambiguous circumstances.

- Assembling and Motivating a Business Team. Measures skills and behaviors required to select the right members of a team and motivate that team to accomplish business goals.

- Efficient Decision Making. Measures skills and behaviors associated with the ability to make effective and efficient business decisions, even in the face of insufficient information.

- Building Networks. Measures skills and behaviors associated with the ability to assemble necessary resources and to create the professional and business networks necessary for establishing and growing a business venture.

- Collaboration and Team Orientation. Measures skills and behaviors associated with being a strong team player who is able to subordinate a personal agenda to ensure the success of the business.

- Management of Operations. Measures skills and behaviors associated with the ability to successfully manage the ongoing operations of a business.

- Finance and Financial Management. Measures skills and behaviors associated with the successful management of all financial aspects of a business venture.

- Sales. Measures skills and behaviors needed to build an effective sales organization and sales channel that can successfully acquire, retain, and serve customers, while promoting strong customer relationships and engagement.

- Preference for Established Structure. Measures preference for operating in more established and structured business environments rather than a preference for building new ventures where the structure must adapt to an uncertain and rapidly changing business context and strategy.

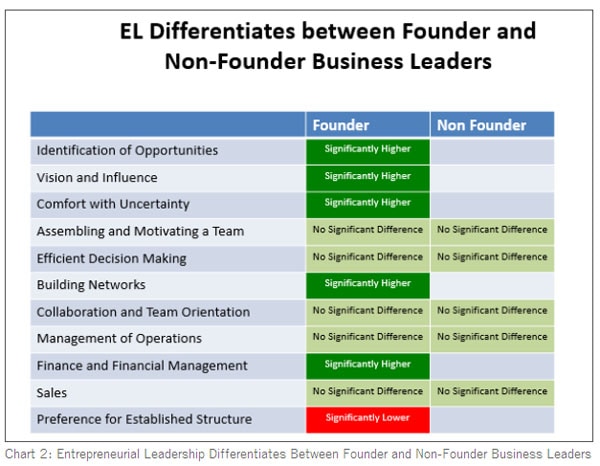

While the 11 factors provided some level of discrimination between founders and non-founders, five factors showed statistically significant differences. For example, founders scored significantly higher than non-founders on “comfort with uncertainty,” “identification of opportunities,” “vision and influence,” “building networks,” and “finance and financial management.” Founders also had significantly lower ratings on their “preference for established structure” dimension (Chart 2).

Although some of the factors—like comfort with uncertainty and the ability to identify opportunities—seemed like obvious markers for entrepreneurial success, the study built a statistically reliable and valid tool that can be used to deepen understanding, not only of founders versus non-founders, but also of differences and similarities among founders who start and grow different types of businesses, between male and female founders, serial founders and first-time founders and founders from different countries.

In addition, a deeper examination of the individual questions that make up each factor provides richer descriptions of specific behaviors and skills that account for the differences in the profile of entrepreneurs who are launching different types of ventures and from many different backgrounds.

Take vision and influence, for example. Although it is a long-standing belief that great leaders have vision and influence, the researchers found that entrepreneurial leaders have more confidence of their abilities than the average leader on this dimension—and that leaders working within established firms actually rated themselves much lower.

Financial management and governance turned out to be another non-obvious differentiator.

“Financial management is a skill that all of our HBS alumni should feel confident in applying,” Kraus says. “Yet among the alumni surveyed in the pilot, those who had chosen to be founders rated themselves as much more confident in their financial management skills—especially those related to managing cash flow, raising capital, and board governance—than did non-founder alumni.”

Self-confidence in financial management and raising capital was especially strong for male entrepreneurs, she says. “Our future research will broaden our sample beyond HBS alumni to enable us to differentiate between those who graduated with and without an MBA, and to assess confidence in raising capital and financial management and a wide variety of other skills by different types of founders and non-founders.”

Efficient management of operations was another crucial, yet less obvious, factor. “While we often think that employees within established organizations would be more confident in their ability to efficiently manage operations, we were surprised to see that it is a distinguishing and differentiating attribute of entrepreneurs,” says Kraus. “All entrepreneurs know that they must do more with less—which means that they must work faster and with fewer resources.”

Differentiating male and female entrepreneurs

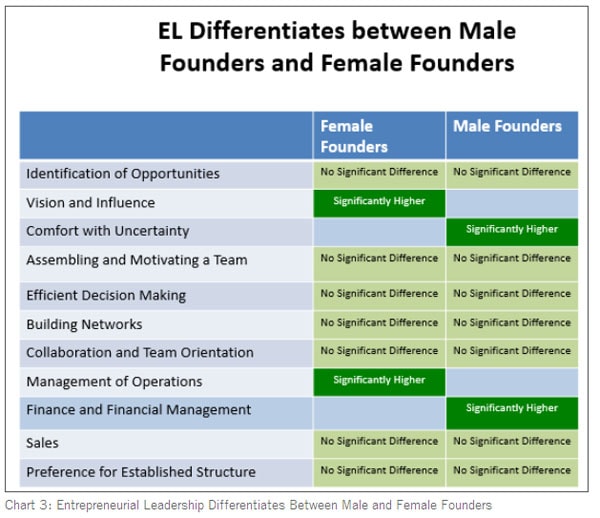

The pilot study allowed researchers to examine gender differences. While men and women rated themselves similarly on many dimensions, women were more confident in their ability to “efficiently manage operations” and in their “vision and influence,” while men expressed greater confidence in their “comfort with uncertainty” and “finance and financial management” (Chart 3).

These differences rang true for Kraus, herself a serial entrepreneur who founded and grew three successful entrepreneurial ventures.

“Successful women entrepreneurs that I know have lots of great ideas, and are super skilled at creating a compelling vision that moves people to action,” she says. “They are also extremely capable of getting lots done with very little resources so are great at efficient management of operations. That said, these same women are often more conservative when forecasting financial goals and with raising significant rounds of capital. And, even if they have a big vision, they are less confident in declaring at the outset that their goal is to become a billion-dollar business.”

Indeed, research confirms observations that women start more companies than men, but rarely grow them as large.

Based on his earlier research, these results also resonated with Tim Butler: “When it comes to self-rating on finance skills, women are more likely than men to rate themselves lower than ratings given them by objective observers. There are definitely implications for educators when lower self-confidence in skills associated with entrepreneurial careers becomes a significant obstacle for talented would-be entrepreneurs.”

The researchers hope to deepen their understanding of male and female entrepreneurial leaders as they collect more data.

Differentiating serial founders and first-time founders

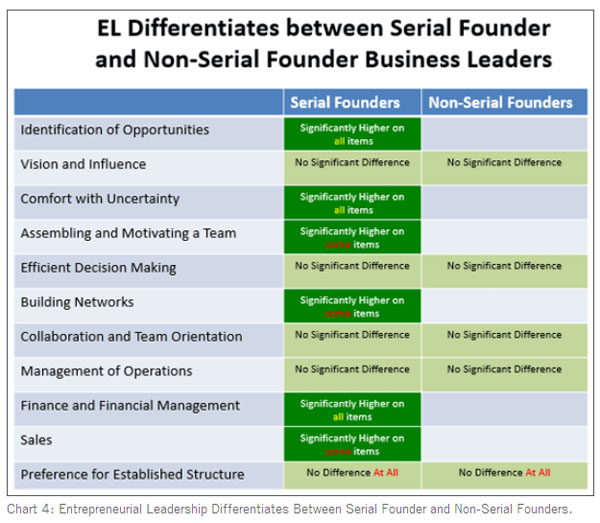

Not all founders are cut from the same cloth, the study underscores. Analysis of the pilot data also revealed important differences between first-time founders and serial founders—those who launch and grow a number of new ventures, such as Elon Musk (PayPal, Tesla Motors, SpaceX) and research team member Kraus (Circles, Spire; peach).

One key difference the research team discovered: serial founders appear more comfortable with managing uncertainty and risk. That doesn’t mean they enjoy taking risks, Kraus says, “but they appear to be confident that they are adept and capable of knowing how to ‘de-risk’ their venture and manage uncertainty from the very beginning” (Chart 4).

While the data are not yet robust enough to say so with certainty, Kraus believes that serial entrepreneurs often enjoy launching businesses where the risk is highest because of confidence in their ability to manage uncertainty, and perhaps because they enjoy the process of creating clarity from uncertainty.

Other factors that set serial entrepreneurs apart from one-timers include confidence in their skills at building networks, securing financing and financial management, and generating creative ways to identify and meet market opportunities.

FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES

As more people take the assessment and HBS develops a richer data set, scholars, educators, entrepreneurs and those who support them will be able to develop insights that will have a number of payoffs.

“The entrepreneurial leaders we know are constantly searching for tools that can help them become more self-aware so they can be more effective,” Kraus explains. “This tool is going to be uniquely useful in that it was specifically developed to help entrepreneurs gain a deeper understanding of the skills and behaviors that they need to be successful.”

In addition, researchers will be able to examine the data by age, gender, country, industry, size of company, pace of growth, and type of venture “to understand the full range of entrepreneurial leadership skills and behaviors, and how different types of entrepreneurs are similar and different,” Applegate says. “These insights will enable us to do a better job of educating entrepreneurs, designing apprenticeships and providing the mentorship needed.”

The data will also be useful in identifying skills and behaviors needed to jumpstart entrepreneurial leadership in established firms, and in understanding how an entrepreneurial leader continues to lead innovation throughout the lifecycle of a business—from startup through scale-up.

“Today, I often see that the creativity and innovation that was so prevalent in the early days of an entrepreneurial venture gets squeezed out as the company grows and starts to scale,” says Applegate. “But, rather than replace entrepreneurs with professional managers, we need to ensure that we have entrepreneurial leadership and creativity in all organizations and at levels in organizations. We hope that our research will help clarify the behavior and skills needed and, over time, will help us track the entrepreneurial leadership behaviors and skills of companies of all size, in all industries, and around the world.”

Given the critical importance of entrepreneurial leaders in driving the economy and improving society, shockingly little is understood about them. The data and analysis emerging from HBS will provide important insights that can help answer the questions, “What makes a successful entrepreneurial leader and how can I become a successful entrepreneurial leader?”

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.