Warning: Scary warning labels work!

If you want to convince consumers to stay away from unhealthy diet choices, don't be subtle about possible consequences, says Leslie John. These graphically graphic warning labels seem to do the trick

San Francisco is in a three-year battle with the American Beverage Industry over whether soda companies can be forced to include consumer warnings on outdoor advertising. The law, which is still being hashed out in court, requires manufacturers to say sugary drinks can lead to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay.

New research from Harvard Business School suggests that even if San Francisco wins its court battle, it may lose the war: Warning labels that aren’t sufficiently graphic don’t work.

“San Francisco policymakers are devoting lots of time and money to fighting it out in court, and they’re operating on the assumption that text warning labels are going to work,” says HBS Marvin Bower Associate Professor Leslie John. “We thought it was important to test it, and our findings suggest that their text label policy might not move the needle much at all, at least when it comes to getting people to buy fewer sugary drinks.”

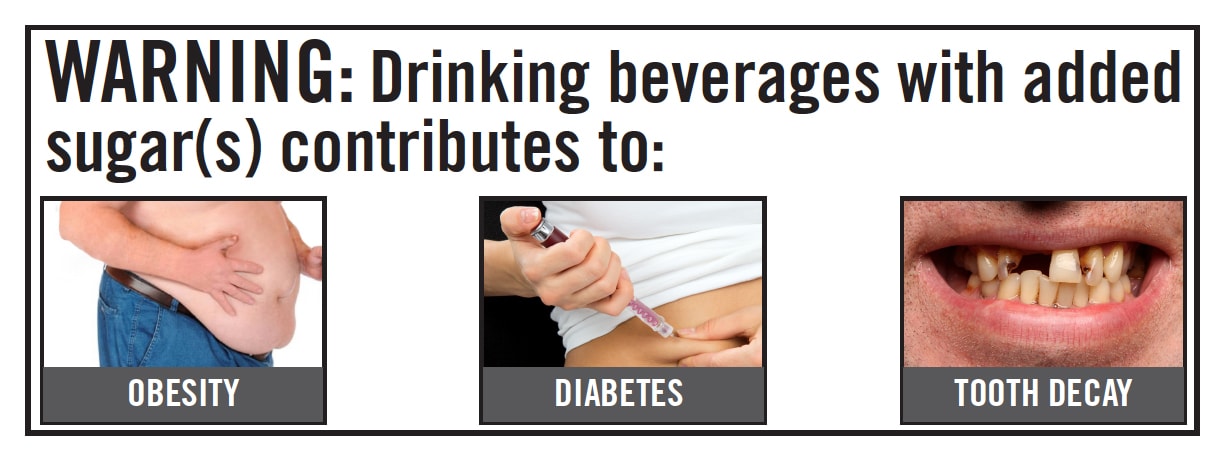

What does move the needle, the researchers found, are warning labels based on graphics instead of text. Graphic graphics, to be specific, splashed with evocative pictures of the after-effects of too much sugar, like a man’s bulging belly, an insulin needle inserted into a stomach, and a mouthful of decaying teeth.

“We were working with a graphics team and they had these stock photos and clip art cartoon images,” John says. “Initially, the pictures weren’t graphic enough. I kept saying, ‘I need rotting teeth!’”

The in-your-face images indeed affected study participants. Not only did they reduce soda consumption, but many also reached for a healthier option instead—bottled water.

Slated to be published in an upcoming edition of Psychological Science, The Effect of Graphic Warnings on Sugary Drink Purchasing is the first real-world test to determine whether warning labels can motivate people to beg off sugary drinks. John co-wrote the article with 2018 HBS doctoral degree recipient Grant E. Donnelly, Harvard School of Public Health doctoral candidate Laura Y. Zatz, and HBS doctoral candidate Dan Svirsky.

How much does fountain syrup weigh?

To study the effectiveness of warning labels, Donnelly, Zatz, Svirsky, and John conducted a field test at a Boston hospital cafeteria for 14 weeks. They displayed three types of labels at different times near bottled drink coolers and on soda fountain machines:

A calorie label that read, “120-290 calories per container. 2,000 calories a day is used for general nutrition, but calorie needs vary.”

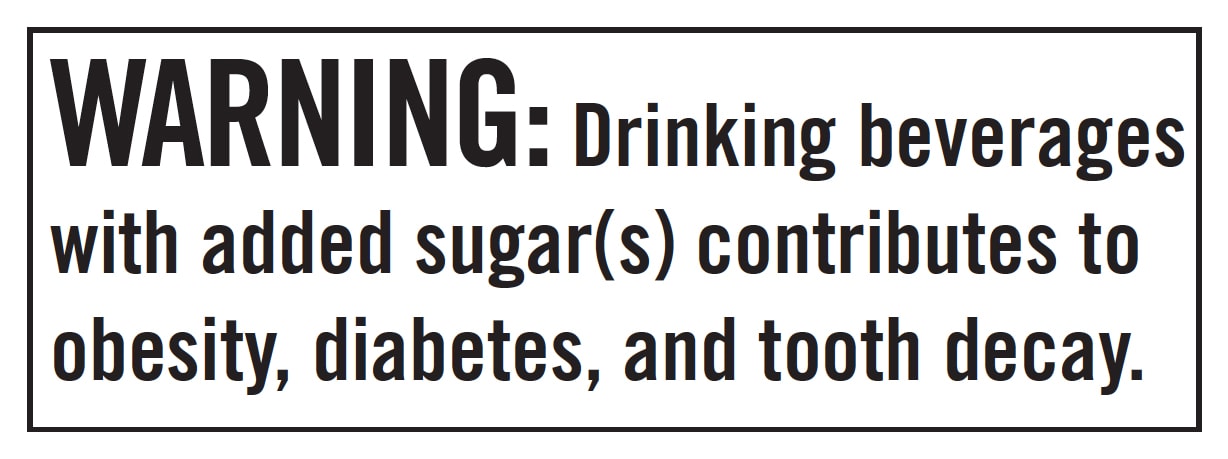

A text warning label with wording similar to what San Francisco used in its labels: “WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay.”

A graphic warning label with text, plus the addition of three unsettling images of a fatty stomach, a needle in a midriff, and rotting teeth.

The researchers gauged the effectiveness of each type of label over two weeks by tracking the amounts and types of beverages purchased, and comparing those results to periods when no warning was posted. They even weighed partially full fountain syrup boxes to determine how much of the sweet stuff had been used each week with carbonated water to make soda.

The results weigh in

Calorie labels and text labels didn’t dissuade people from buying soda; on average, the same number of sugary drinks were purchased during those periods as the periods without any labels.

The only warning that slowed soda sales were those with graphics and text. The share of sugary drinks purchased in the cafeteria experiment during those periods dropped from 21.4 percent without labels to 18.2 percent with graphic labels, a decline of 3.2 percentage points. For some consumers, the bulbous bellies, protruding needles, and nasty teeth changed their habits; as soda sales dropped, bottled water sales rose from 24.9 percent to 28.1 percent.

Graphic warnings worked by grabbing the attention of consumers, forcing them to think about the risks involved, and prompting them to consider the negative health consequences, the researchers found.

Compared to text warnings, graphic warnings worked better by grabbing the attention of consumers

Compared to text warnings, graphic warnings worked better by grabbing the attention of consumers “I’ve gotten some early feedback from people saying that [3.2 percentage points] is not a big effect,” Donnelly says. “Going into this, we weren’t sure if we’d see any difference. But we observed about 200 people in a two-week period making a drink change. To impact that many people, we think that’s pretty significant.”

John adds, “Imagine if we piled up all the sugar that people didn’t eat over those two weeks. It is a small percentage point difference in absolute terms, but then when you think about all that sugar, it’s a bigger deal.”

The results may mollify retailers and other venues that sell a variety of drinks. If warning labels are present, consumers still purchase drinks; they just choose healthier options. “Cafeteria sales were neutral. We didn’t see a decrease in drink sales,” John says.

Soda makers and suppliers, however, may suffer losses if graphic warnings become standard. (That’s the goal, after all.) But John believes many drink companies are aware that health-conscious consumers are veering away from soft drinks, so they are already adding healthier alternatives to their product lines.

“Soda companies are in a really challenging spot, since their responsibility to their shareholders is to make money, and their go-to way of doing this has been by selling junk food,” she says. “But, you can see this trend where they’re trying to juggle their product portfolios. For example, you see the emergence of smaller serving sizes, and more water and mid-calorie options.”

Cities look for public support

If cities want to win public approval for labels, this research suggests it might behoove them to publicize information about their effectiveness. A related online survey of 400 participants showed that once people learned that graphic warnings led to a drop in sugary drink purchases, they supported the labels in much greater numbers.

One question that remains unanswered by the study is whether the warnings spur consumers to change their behavior over the long term. “We don’t know whether the graphic warning labels would have a sustained effect,” John says. “We had them up for two weeks; it’s possible that if they are up all the time, people will adapt to them and their impact might lessen over time.”

Another issue to consider: While the research highlights the benefits of graphic labels, John realizes the shocking images may also raise concerns, such as whether they “fat shame” people. “There could be situations where graphic warning labels could make people feel badly about themselves, so are we introducing another problem? Or will people tune them out if they think they’re offensive?

“The conclusion of this research is not that graphic labels are the answer to all of our consumption problems,” she says, “but we do find that they shift people to water at least in the short run, and we think that’s a pretty cool result.”

San Francisco’s 2015 warning label law was the first initiative of its kind in the nation. Some communities have attempted other measures to reduce the public’s soda consumption, including New York City’s proposed cap on portion sizes and Berkeley’s one-cent-per-ounce tax on sugary drinks.

Donnelly hopes these research findings spur more effective labeling policies that not only lead people to make healthier choices, but encourage companies to work with public officials for the greater good.

“I hope it can inform some of the conversations firms are having with policymakers,” he says. “These firms can respond in a positive way—by giving more shelf space to healthier foods.”

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.