Rush Limbaugh, talk radio's conservative provocateur, dies at 70

Limbaugh became a singular figure in the American media, fomenting mistrust, grievances and even hatred on the right for Americans who did not share his and his followers' views

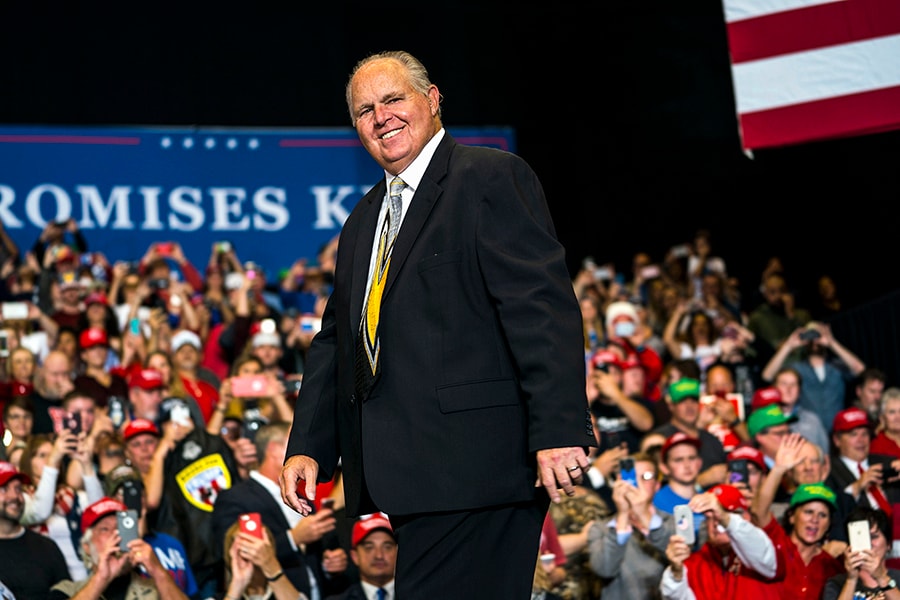

Rush Limbaugh takes the stage during a re-election campaign rally with President Donald Trump in Cape Girardeau, Mo., Nov. 5, 2018. Limbaugh, the relentlessly provocative voice of conservative America who dominated talk radio for more than three decades with shooting-gallery attacks on liberals, Democrats, feminists, environmentalists and other moving targets, died on Wednesday, Feb. 17, 2021. He was 70. Image: Doug Mills/The New York Times

Rush Limbaugh takes the stage during a re-election campaign rally with President Donald Trump in Cape Girardeau, Mo., Nov. 5, 2018. Limbaugh, the relentlessly provocative voice of conservative America who dominated talk radio for more than three decades with shooting-gallery attacks on liberals, Democrats, feminists, environmentalists and other moving targets, died on Wednesday, Feb. 17, 2021. He was 70. Image: Doug Mills/The New York Times

Rush Limbaugh, the right-wing radio megastar whose slashing, divisive style of mockery and grievance reshaped American conservatism, denigrating Democrats, environmentalists, “feminazis” (his term) and other liberals while presaging the rise of Donald Trump, died Wednesday at his home in Palm Beach, Florida. He was 70.

His wife, Kathryn, announced the death at the start of Limbaugh’s radio show, a decadeslong destination for his flock of more than 15 million listeners. “I know that I am most certainly not the Limbaugh that you tuned in to listen to today,” she said, before adding that he had died that morning from complications of lung cancer.

Limbaugh had revealed a diagnosis of advanced lung cancer last February. A day later, Trump awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, during the State of the Union address.

Since his emergence in the 1980s as one of the first broadcasters to take charge of a national political call-in show, Limbaugh transformed the once-sleepy sphere of talk radio into a relentless right-wing attack machine, his voice a regular feature of daily life — from homes to workplaces and the commute in between — for millions of devoted listeners.

He became a singular figure in the American media, fomenting mistrust, grievances and even hatred on the right for Americans who did not share his and his followers' views, and he pushed baseless claims and toxic rumors long before Twitter and Reddit became havens for such disinformation. In politics, he was not only an ally of Trump but also a precursor, combining media fame, right-wing scare tactics and over-the-top showmanship to build an enormous fan base and mount attacks on truth and facts.

©2019 New York Times News Service